The great estates of the Gilded Age were more than lavish displays of wealth for the American aristocracy c. 1870-1917, they supported the economy of the local communities and encouraged development. As they declined, many of the surrounding towns followed suit unless they were able to find other means to sustain themselves.

Two hours’ drive north of New York City, between the towns of Hyde Park and Rhinebeck, lies the small village of Staatsburg. The village today is a lovely, quiet, rural community with the restaurant River & Post located prominently on the main road, the small, brick post office, St. Margaret's Episcopal Church, the community library, and then the long expanse of the Dinsmore Golf Course, one of the oldest public golf courses in the country, which was created by the wealthy owners of the estates which once adorned the riverfront.

There were four such grand estates in Staatsburg c. 1915: The Point (the Hoyt Estate), Staatsburgh (the Mills Estate), The Locusts (the Dinsmore Estate), and Hopeland (the Huntington Estate). The Point, Staatsburgh, and The Locusts were all connected originally to the Livingston family, regarded as "America's Aristocracy", while Hopeland was associated with the Dinsmore family which came to own The Locusts and its vast acreage.

All four of these estates once employed the majority of the citizens of Staatsburg, directly or indirectly, and although the days of the Gilded Age in America are long gone one can still feel those times as one stands on the hill outside the mansion of Staatsburgh, walks through the woods to the ruins of The Point or strolls the pleasant paths through the grounds of Hopeland.

European Development in the Hudson Valley

The Hudson River Valley was discovered by Europeans in the 17th century and was described as unlike anything the Dutch Captain Hendrick Hudson had ever seen. It was literally a new world of endless wilderness covering high hills and valleys cut through by a river so wide it made the Amstel seem like a stream. It was not long, however, before the European settlers began transforming the land so it would resemble the old world they had left.

Lots were cleared and buildings raised, and the paths worn through the woods by Native American tribes like the Mahican, Wappinger, and Munsee became roads, which, in time, were paved. By 1664, the English had taken the land from the Dutch and increased development, which would expand even further after the American War of Independence ended in 1783. Over the next one hundred years the land would change so significantly that it would have been unrecognizable to the early Dutch settlers and, by 1883, industrialization and urbanization was increasingly daily.

Those affluent members of society, industrialists, railroad tycoons, investment bankers, who lived in New York City, more and more sought refuge in lavish country estates they could retreat to and chose the Hudson Valley for its beauty and proximity. The scholar Harvey K. Flad comments on this, writing, "The buildings and the carefully landscaped grounds became a parlor in the wilderness" (359). The wealthy could have all the comforts of their urban homes in a rural setting and created artificial landscapes in the wilderness of the Hudson Valley in which they lived their dreams of ease and luxury.

These rich captains of industry did not just happen upon the Hudson Valley in the 19th century, however; the region already had a reputation for natural beauty which encouraged the more affluent in society to build their estates along the river a century earlier.

The Mills Estate

The first estate was developed in 1792 when New York's third governor, Morgan Lewis (l. 1754-1844), built a 25-room country manor in Staatsburg overlooking the river. The 1,600-acre parcel belonged to his wife, Gertrude Livingston (l. 1757-1833), whose family lived north of the village in Clermont. The original house burned down in 1832, and Lewis had a new Greek Revival home built in its place.

The house was passed down in the family until inherited by Ruth Livingston Mills (l. 1855-1920) and her husband Ogden Mills (l. 1856-1929), a financier and philanthropist, in 1881 who named their estate Staatsburgh. Mrs. Mills was a member of high society and, as a Livingston, felt she should set the standard by which other estates in the Hudson Valley would be measured. To that end, in 1895, she hired the firm of McKim, Mead & White to enlarge the mansion. The great architect Stanford White (l. 1853-1906) added two wings to the existing house and a third floor, completely engulfing the previous structure except for the massive central portico with its Ionic columns. The renovation took 18 months and cost $350,000.000. When White was finished the new home was a mansion in the beaux-arts style with 65 rooms, 14 bathrooms, indoor plumbing with hot and cold running water, and 750 gas lights which were powered by a pump house on the river generating electricity. The historian Conrad Hanson notes:

Predating the Vanderbilt mansion in Hyde Park and the Astor's Casino at Rhinecliff, no other place in the Hudson Valley at that time could come close to competing in terms of scale or splendor with Ruth and Ogden's new 65-room palace. (7)

Among the many ladies of high society whom Ruth Livingston Mills wished to lord her new estate over, none would have been as important as Caroline Schermerhorn Astor (l. 1830-1908) who was leading the New York Society social scene at the time. Mrs. Astor was related to Elizabeth Schermerhorn Jones (l. 1810-1878) who, in 1853, built the grandest of all Hudson Valley estates in the nearby village of Rhinecliff.

Jones' estate, known as Wyndclyffe, was a three-story, 24-room mansion on 80 acres (32 ha) of land with a carriage house, boathouse, and dock, all so grandly opulent that others spent lavishly to make their own estates just as impressive. The Wyndclyffe estate is said to have inspired the phrase "keeping up with the Joneses" referring to trying to match the affluence of one’s neighbor.

Even though Miss Jones died in 1876, and Wyndclyffe was less impressive in 1895 than it had been, when Ruth Livingston Mills decided to remodel her home in Staatsburgh, she would have had it in mind to outdo the fame of Wyndclyffe; and she succeeded. Wyndclyffe's grand days were already a thing of the past when Staatsburgh was at its peak in terms of high society between the years 1900-1915. Lavish parties were regularly held there with only the most select guests including the author Edith Wharton (l. 1862-1937, a niece of Elizabeth Schermerhorn Jones) who would later use Staatsburgh, Wyndclyffe, and the Hudson Valley in her novel The House of Mirth and mentions them in her memoir A Backward Glance.

In addition to the mansion house, Staatsburgh had the previously mentioned pump house by the river, a boathouse, multiple outbuildings, and was a working farm on which Ogden Mills raised prize-winning cattle and grew flowers in the elaborate greenhouses which covered portions of the estate's gardens. A member of The Jockey Club, Mills raced prize-winning horses which won in numerous prestigious events such as the Grand Prix de Paris in 1928.

Each Christmas Ogden Mills gave every servant a 20-dollar gold piece and was extremely generous in his gifts to the village which included stained glass windows imported from Chartres for St. Margaret's Church, ambulances for local hospitals, and state-of-the-art equipment for the local firehouse. This is more impressive when one understands that Staatsburgh was not the Mills' primary residence. The Mills only occupied their mansion in Staatsburg September through November or December; they had five other homes including a Paris residence next door to the famous sculptor Auguste Rodin.

Hoyt Estate: The Point

To the south were the Mills' neighbors and relatives, the Hoyts, who had their own mansion, The Point, on a high crest of a hill with a wide river view. Historian Francis R. Kowsky notes that the house was a two and a half story bluestone in the style of Hudson River Gothic, designed by Calvert Vaux (l. 1824-1895) and goes on to describe the way the landscape worked with the house:

The Hoyts' gently undulating land supported many fine trees and offered numerous opportunities for Vaux to try out the landscape and design skills [he had learned]. With his guiding principle in mind that the "great charm in the forms of natural landscape lies in its well-balanced irregularity", Vaux proceeded to lay out roads and to site the house and other buildings with the aim of preserving and enhancing the rich treasure of scenery that nature had stored up at the Point. (1)

The Point was built between 1855 and 1857 for the wealthy merchant Lydig Munson Hoyt (l. 1821-1868) and his wife Blanche Geraldine Livingston (l. 1822-1897). Vaux, best known for his work with Frederic Law Olmstead (l. 1822-1903) on New York's Central Park, positioned the house carefully in accordance with the sweep of the land so it would seem an organic outgrowth of its surroundings and then designed the entire estate to give visitors the impression of entering another world as soon as they passed through the gates.

Elaborate gardens and wooded glens graced both sides of the long driveway which wound through the forest and up to the mansion. Although the house had only seven rooms it was still considered a grand manor situated on 92 acres of a working farm with greenhouses, stables for the horses, and barns for the other animals.

The Locusts

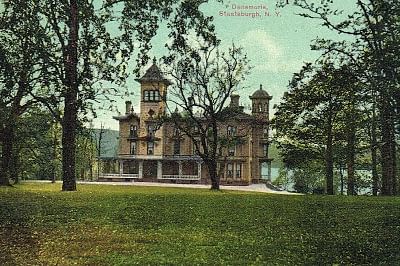

On the other side of Staatsburgh estate rose the towers of The Locusts which was first developed by Henry Brockholst Livingston (l. 1757-1823) in 1797 and named after the black locust trees which grew abundantly on the grounds. His property included a half-mile along the Hudson River and over a thousand acres of land. In 1871 the successful shipping magnate William Dinsmore (l. 1810-1888) bought the property, tore down the old manor house, and built a four-story, 92-room Italianate-style mansion on the site.

Like the Mills and the Hoyts, Dinsmore operated a farm on his property and was especially well known for his flowers and exotic plants. The grounds were completely renovated under Dinsmore's care and he insisted on clover-shaped ornamentation on all his buildings to mark his vast estate; a design which can still be seen on existing buildings in the region today miles away from the village of Staatsburg.

Hopeland

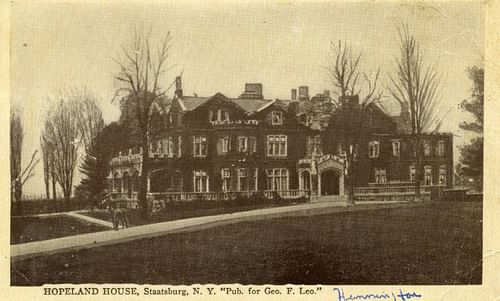

To the north of The Locusts was the fourth estate known as Hopeland which was first developed in 1859 by Major Rawlins Lowndes and his wife Gertrude Livingston who had Calvert Vaux design their house as he had The Point. In 1907 the architect and tennis celebrity Robert Palmer Huntington (l. 1869-1949) acquired the 300-acre (120 ha) property and enlarged the main house to create a 35-room Tudor Revival mansion. Huntington had married Helen Dinsmore in 1892 and the families lived easily as neighbors.

As with the other estates, Hopeland was a working farm, and it seems as though Huntington was given leave to use the Dinsmore estate's barns. The Huntingtons raised three children on the estate all of whom married into respectable, and wealthy, families. The eldest, Helen Dinsmore Huntington (l. 1893-1976), was married to Vincent Astor (son of John Jacob Astor IV who died on the RMS Titanic) for 26 years until they divorced, and she married the wealthy real-estate broker Mr. Lytle Hull (l. 1882-1958), a friend of Astor’s, in 1941.

Destruction, Repurpose, & Decline

Helen Hull inherited The Locusts (from her grandfather) and Hopeland (from her father) and disposed of them both. At some point between 1940 and 1950 she had the mansion at Hopeland dismantled by local workers, who used the windows, doors, and trim in other projects in the community, and then had the house destroyed. She retained the land, however, which she eventually donated to the New York State Parks Department. She then had the 92-room mansion of The Locusts dismantled and built a smaller Neo-Baroque manor in its place. With the other estate owners, Mrs. Hull had developed the golf course for private use and now donated it to the state of New York's Parks and Recreation Department for the public.

The Mills Mansion, though still standing, was no longer an estate by this time. In 1938 the mansion and grounds of Staatsburgh were donated to New York State for use as a park by one of Ogden and Ruth Mills daughters, Gladys Mills Phipps (l. 1883-1970), in honor of her parents. Only the manor of The Point now remained as it had been at the peak of the Gilded Age and was still inhabited by the Hoyt family.

In 1963, when the "master builder" Robert Moses (l. 1888-1981) was acquiring green space along the Hudson River for use as public park space, the Hoyt family was evicted, and the house seized under eminent domain. The original plan was to demolish the manor and build a public swimming pool, but the community objected. Instead, the house was left to decay and the grounds and stables fell into ruin.

Less than 60 years earlier, these four estates were the life blood of the community. The grand hotels which once lined the streets of Staatsburg and Route 9 catered to guests of the Hoyts, Mills, Dinsmores, and Huntingtons as did all of the other businesses up and down the river. Staatsburg once had its own train station, sidewalks with streetlamps, pubs, restaurants, shops, and factories, and at least four hotels in the village alone, not counting those along Route 9; today there is only one restaurant in the village and all the rest - including the sidewalks - are gone.

Conclusion

The Gilded Age of the very rich passed into memory with the advent of income tax in the United States in 1913 and the War Revenue Act of 1917 which taxed the rich further to help pay for World War I. The stock market crash of 1929 and the Great Depression of the 1930s contributed to the decline of the estates and descendants of the Gilded Age millionaires either donated their family homes (like Gladys Mills Phipps), destroyed them (like Helen Hull), sold them, or, like Helen Hoyt, were evicted from the property to make way for a new paradigm of society in which the estates played no part.

Except for The Locusts, however, one may still walk the grounds and visit the houses which once gave Staatsburg its life. The Point is presently under renovation courtesy of the Calvert Vaux Preservation Alliance and the National Park Service. If you walk down the river path at Staatsburgh, pass by the small beach, and continue on into the woods, always staying on the path and heading upwards, you will find The Point in surprisingly good condition for a house which has been vacant for over 50 years. One is not allowed inside the house, which is now fenced off, but one can visit and see the outbuildings, which were once the stables, the greenhouse, and barn.

Leaving Mills and heading north on Old Post Road, you will pass by The Locusts which is today privately owned by hotelier Andre Balazs as a farm and prestigious center for conferences and high-end weddings. One may visit by appointment only. At the northern end of the village, just past The Locusts, the grounds of Hopeland are open to the public as a park. People can still enjoy the grounds, bridges, and paths throughout the estate and the site has become popular with birdwatchers, dog-walkers, and artists.

Mills' mansion of Staatsburgh remains almost completely intact, with tours of the home offered Thursday through Sunday and the grounds open seven days a week dawn till dusk (although Covid restrictions are currently still in place as of June 2021). Special tours are offered as well as talks on the Titanic as the Mills had tickets for return passage on the doomed ship in 1912. A tour of the mansion is a walk through history as the guides take the visitor back in time to the Gilded Age and the era of high society when the affluent of America looked out through the long windows of their parlors in the wilderness and created the world they wanted to see.

However one may view the wealthy of the Gilded Age today, they were the celebrities of their time, and their weddings, scandals, and grand parties were the talk of the town and the stuff of high newspaper sales. More importantly, though, they provided for the communities which supported their way of life, and after their time had passed, small villages in America like Staatsburg would have to fend for themselves, for better or worse.