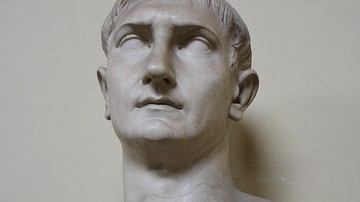

The Dacian Wars started after Decebalus (r. c. 87-106 CE) raided the Roman province of Moesia in 85 CE. Emperor Domitian's (r. 81-96 CE) Dacian campaigns in 86-87 CE reached an uneasy peace, but the conflict was renewed under the reign of Emperor Trajan (r. 98-117 CE). Trajan's Dacian Wars, recorded on Trajan's Column, ended with Decebalus' death, and Dacia became a Roman province.

Domitian's Dacian Campaigns

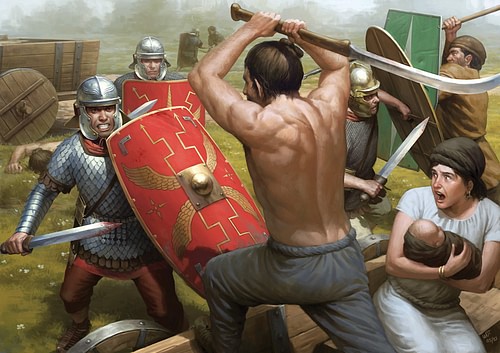

In 85 CE, Decebalus (r. c. 87-106 CE), the future king of Dacia, invaded the Roman province of Moesia. The provincial governor Oppius Sabinus met the Dacian army with Legio V Macedonica, however, the governor was among the heavy casualties, forcing the legion to retreat. The IV Flavia Felix arrived from Dalmatia too late to help. Decebalus and his army had already returned to Dacia, having: sacked cities and taking thousands of prisoners.

Responding to the defeat, in 86 CE, Roman emperor Domitian (r. 81-96 CE) organized his legions and went on the offensive. With the support of five legions, the prefect of the Praetorian Guard, Cornelius Fuscus, crossed the Danube into Dacia where he was immediately attacked by Decebalus. The assault cost the prefect his life, and his beleaguered legions retreated across the river into Moesia. Although sources disagree, during the assault, Legio V Alaudae was supposedly annihilated and its flag captured. Some historians believe the legion was routed later either during Trajan’s campaign or in the war against the Sarmatians in 92 CE. With troops remaining to garrison the borders, Domitian returned to Rome to rethink his offensive.

In 88 CE the Roman commander Tettius Julianus led his legions - VII Claudia, I Italica, IV Flavia Felix, and II Adiutrix - into central Dacia. In addition to these legions, I Adiutrix and XIII Gemina is believed by some to have also participated in Dacia. Although Julianus quickly routed the Dacians at Tapae, the Dacian commander and high priest Vezinas escaped. After the battle, the Romans made camp for the winter outside the Dacian capital of Sarmizegetusa Regia. During the winter, with the river frozen, the Sarmatian Iazyges and Quadi took the opportunity while Rome was engaged in the Saturninus Revolt in Germany - VII Claudia had been recalled - and marched into Moesia, sacking towns. At the same time, Decebalus mobilized his army to defend the capital against the Romans. With the Sarmatians behind him and realizing he might be trapped, Julianus fell back into Moesia. Leading an army of his own, Domitian went on the march, initially intending on battling the Sarmatians; however, after they withdrew across the Danube, he joined forces with Julianus in Moesia.

Refusing a peace offering from Decebalus, Domitian marched his army into Pannonia in what he believed was an act of revenge but was quickly pushed back by the Marcomanni. Receiving a second offer of peace, Domitian decided it was in his best interest to agree to the Dacian offer; an ill-considered treaty was reached that included a yearly payment of gold to the Dacians. The Dacians agreed to a withdrawal from Moesia and to return prisoners of war. The Roman Senate and army were both displeased with the treaty. It was, in their minds, a sign of weakness. Following the treaty, Moesia was divided into two separate provinces: Upper or Superior Moesia and Lower or Inferior Moesia. Four legions were assigned to Moesia while another four were stationed in Pannonia.

The emperor viewed his encounter with the Dacians differently. Following the celebration of the three-day Roman Secular Games, Domitian held a Roman triumph to celebrate his defeat of the Chatti and Julianus’ success in Dacia. In his The Twelve Caesars, historian Suetonius (c. 69 - c. 130/140 CE) wrote of the emperor’s campaign against the Sarmatians and Dacians:

Some of Domitian’s campaigns ... were quite unjustified ... but not so against the Sarmatians, who had massacred a legion and killed its commander. And when the Dacians defeated first the former consul Oppius Salinas and then his successor, the praetorian prefect Cornelius Fuscus, Domitian led two punitive expeditions in person. After several indecisive engagements, he celebrated a double triumph over the Chatti and Dacians but did not insist on recognition for his Sarmatian campaign ... (299)

Trajan's Dacian Wars

Another war against Dacia was inevitable. Trajan was determined to defeat the Dacians where Domitian had failed. Historian Barry Strauss wrote that Domitian had accepted compromise with the Dacians while "Trajan conquered it, annihilated its ruling class, and opened the country to colonization by Roman veterans" (163). His desire to go to war against the Dacians may not only have been an act of revenge but also a place to demonstrate his military leadership. Trajan spent almost half of his reign away from Rome, on campaign in Roman Britain and in Parthia, but his greatest success in Roman warfare would be in Dacia. The spoils of the war not only made him rich but also financed a new Roman forum, the Baths of Trajan, and Trajan’s Aqueduct (Aqua Traiana). Unfortunately, his personal account of the war, Dacica, is lost, and so the majority of our present information on the Dacian conquest is derived from Trajan’s Column, a spiral relief of 155 scenes.

Trajan understood but did not trust the Dacian king. Decebalus was considered a shrewd warrior and an expert in both ambushes and pitched battles. He was a master of timing and an astute manager of both victory and defeat. Trajan must have realized this, and when he saw the Dacian king was on the move, he decided to attack.

In the spring of 101 CE, Trajan marched out of Rome. There were already four legions stationed in Moesia - I Italica, IV Flavia Felix, V Macedonica, and VII Claudia - all ready to cross the river. By his departure, additional legions were on the way: I Adiutrix, XIV Gemina, XV Apollonius, X Gemina, and II Adiutrix. More were soon to arrive: XIII Gemina and I Minervia. Accompanied by the Praetorian Guard prefect Claudius Livianus and the commander Lucius Appius Maximus, Trajan and the legions arrived at Viminacium on the Danube where they joined the emperor’s nephew (and future emperor) Hadrian (r. 117-138 CE).

Realizing the Roman army was across the Danube, Decebalus, along with the Sarmatian cavalry and Roman deserters, prepared to meet the Romans. As Trajan’s legions broke into marching camps, envoys from the Dacians arrived to talk peace with Trajan, but they were quickly dismissed. Whether or not his offer of peace was a ploy to delay Trajan, Decebalus’ warriors attacked the Roman advance parties. Marching camps were next on the Dacian hit list, but his troops were quickly repulsed as were the Sarmatians. In an attempt for a peaceful solution, Trajan sent two envoys, Lucius Sura and the prefect Livianus, to discuss terms, but Decebalus refused to see them. With the peace talks rejected, Trajan’s army crossed through the mountains attacking Dacian fortresses. At one of the fortresses, Trajan discovered the eagle taken from the routed V Alaudae. Finally, Trajan reached Tapae, the site of Julianus’ victory two decades earlier. The ensuing Second Battle of Tapae came with a cost of heavy casualties on both sides, but Decebalus retreated.

With the onset of winter, Trajan withdrew his army southward to the Danube, crossing the river at the Iron Gate. Seeing the retreat of Trajan, Decebalus seized the opportunity and launched an attack on Roman auxiliary forts while the Sarmatian cavalry rode into Moesia. Trajan immediately led his infantry across the river. In what would later be called the Battle of the Carts, Trajan cut off the Dacian baggage trains and killed those accompanying it. Meanwhile, the Roman legions remaining in Moesia repulsed the Sarmatians and, despite their own heavy losses, slaughtered the Sarmatian cavalry in the Battle of Adamclisi. The Dacians and Sarmatians withdrew and prepared for another day.

In 102 CE, having divided in army into two columns, Trajan and his army crossed the Danube and marched towards the Dacian capital, preparing for a siege. Along the way, the Romans attacked Dacian fortresses. The Dacians attempted to stop the Romans but failed; even Decebalus’ sister was captured. At the capital, the emperor reunited with Lucius Maximus. The Dacian king sent envoys to speak to Trajan, who in response sent Sura and Livianus to discuss peace terms with the envoys. The peace terms were quickly accepted by Decebalus. In the peace treaty, the Dacian king agreed to surrender an area in western Dacia where Roman settlers would eventually be relocated. Along with other conditions, the previous tribute paid via the old Domitian treaty was to cease.

Trajan returned to Rome to begin a long series of building projects. The Roman legions returned to their home bases while garrisons remained to protect the newly acquired territory. For a short time, there was peace. Of course, the emperor did not trust Decebalus who prepared for another assault on the Romans, seeking allies and rebuilding fortresses. After returning to Rome, Trajan formed two new legions: II Traiana, who was sent to Syria, and XXX Ulpia Victrix, who would later accompany him on his return to Dacia.

The Second Dacian War

In the summer of 104 CE, Decebalus learned that Trajan was rebuilding his forces along the Danube and wanted to know the emperor’s plans. Meeting with Trajan’s legate in Dacia, Pompeius Longinus, to supposedly discuss further peace plans, the king instead chose to hold Longinus as his prisoner. In a message sent to the emperor, Decebalus agreed to return the legate in exchange for the land lost in the treaty. While Trajan considered the plan, Longinus sent a courier with a letter to Trajan to "convince" him to comply with Decebalus’ wishes. However, he outsmarted the king and committed suicide. Decebalus was furious, and in the spring of 105 CE, Dacian troops attacked several Roman auxiliary forts. In response, Trajan and his Praetorian Guard sailed across the Adriatic to Dalmatia. From there they marched to the Danube and followed it along to Viminacium. He then continued on to Drubeta where he connected with his legions; one of them was Legio I Minervia under the command of Hadrian.

The Roman legions - there would eventually be twelve - were now gathered on both sides of the river at Trajan's bridge, a new permanent bridge built by Syrian engineer Apollodorus. Dividing his forces into four, Trajan crossed into Dacia leading one column while Lucius Licinius Sura, Lucius Appius Maximus, and Lusius Quietus led the other three. The Romans began their long march to the capital by assaulting Dacian fortresses at Costeri, Blidaru, and Piatra Rosie. At the onset of summer, Trajan reached the Dacian capital. Wanting Decebalus more than a treaty, Trajan rejected a plea for peace and placed the Roman artillery at the city walls and prepared to attack.

As they waited, fires began to break out throughout the city. The following day the Romans entered the burning city and would learn that the king had ordered many of his nobles to drink poison, but he, instead, escaped. They also learned from surviving nobles of the king’s hidden treasure. Apparently, Decebalus had temporarily redirected a nearby river and buried his gold and silver. Learning this, Trajan ordered his legions to redirect the river and find the hidden treasure: 360,000 pounds of gold and 730,000 pounds of silver.

Dacia Becomes a Roman Province

While Trajan and his legions began the search for the treasure and the Dacian king, Decebalus was in the mountains attempting to rebuild his depleted army. Roman commander Maximus rode in the pursuit of Decebalus. Failing to attack a Roman marching camp and fearing capture, Decebalus committed suicide in front of commander Maximus before he could be taken prisoner. Maximus dismounted, beheaded the corpse, and sent Decebalus' head to Rome.

After his victory, Trajan returned to Rome with 51,000 prisoners. He had earned the title of Dacicus, and the celebration in Rome lasted for 123 days. Victory games saw 10,000 gladiators fight and 10,000 animals slaughtered. Dacia was now a Roman province, and Moesia became the home of the legions XIII Gemina, I Italica, V Macedonica, VII Claudia, and XI Claudia.