In this interview, World History Encyclopedia is joined with Elodie Harper, the author of the novel The Wolf Den.

Kelly (WHE): Do you want to start us off by telling us what the book is about?

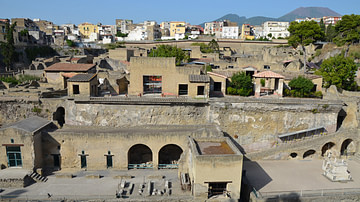

Elodie Harper (author): Hi, it is so nice to be here with you. Thank you for having me! The Wolf Den is set in ancient Pompeii, and it is the story of the women who lived and worked in the lupanar, which means "wolf den" and also means brothel. It is a building that still survives today. The book is based around that little neighbourhood, and it follows the story of the five women who work there and the story of one woman, in particular, Amara, and her quest for freedom because she wants to get out of the brothel.

Kelly: At the beginning of every chapter, you have got a quote from either an ancient writer or from graffiti from Pompeii. Do you want to tell us a little bit about how that formed and also just how you incorporated it into the story, and why graffiti?

Elodie: So, as I know you know about Pompeii, one of the most extraordinary things about the town is when Vesuvius erupted in 79 CE, it preserved a lot of the town at the same time as it destroyed it. The evidence of how people lived, whole houses have been preserved. Streets, taverns, and the brothel, obviously. The graffiti, which is in houses and on the streets, is a unique look at the way ordinary people spoke. We have people talking in bars, not elite Roman speakers. The first thing the graffiti does in Pompeii gives us voices of ordinary people.

The second thing it does is give us a huge range of human emotions. Some of it is very obscene or very insulting or just the kind of stuff that you get anywhere with people sounding off. Some of it is very thoughtful and reflective. There are some genuinely touching love messages on there. There are people's anxieties, prayers to the gods, conversations between people, and a lot of sexual stuff as well. So, you get this extraordinarily vivid portrait of life in Pompeii, and I wanted to try and capture something of that voice, which in translation sounds incredibly modern and vibrant and humorous. I wanted to incorporate it into the book, but I did not have a set method of doing that. I looked at the graffiti first, I had an idea of what it said, and I knew basically where I wanted to go with my story, and it was a strange kind of, almost organic process of fitting it together. I used a lot of Ovid's Art of Love, so I knew that text was going to be important in the chapter headings, but I did not always choose exactly which point of those texts I would use, from the Art of Love in particular, until afterwards.

Kelly: I definitely felt that with each chapter, you could feel the quote that you put at the beginning permeate through the story in a way that felt really organic. We have probably seen modern versions of some of the quotes you have added in our daily lives. Did you feel closer to the ancient world as you were working on this story because of the graffiti?

Elodie: Definitely, and some people have commented about the modern language in the book, but that was one of the joys of writing about the ancient world in particular, because it comes to us in translation. So, it is modern, in my view. If you read a decent translation of an ancient text, it is often translated into highly colloquial, contemporary language because to the people at the time, that is what it would have sounded like. Whereas if you write about 16th-century England, you cannot do that because we actually have the text in our own language of how they spoke. I have such admiration for people who pull that feat off, I think it is just a profound challenge to do that, and it is much easier with the ancient world.

Sometimes the stuff that people say also illustrates the strangeness and difference of life back then, where there are references to things that were obviously very common for them but are not for us. It is not always a way of making us feel like this could have happened yesterday, but it definitely feels very immediate. The whole of Pompeii is like that, as a site, because you can walk down the streets, and although they are semi-ruins, they are still recognisably the streets that people from 2,000 years ago would know. They would know where they were, and if they walked into their house in the state it is in now, 2,000 years later, they would know that was their house. The paintings survived on the floors. It is the most extraordinary ancient site because of its preservation and the brothel in particular. It has been conserved especially well, and they reconstructed the upper level, so it feels very complete. The lower level where you go in is astoundingly well-preserved and it is extraordinarily like what it would have been for the women there 2,000 years ago. It is impossible not to feel quite a profound connection to the physical sites.

Kelly: Did you walk the streets of Pompeii and that is where this story began?

Elodie: It did not necessarily begin there because I went there especially for a research trip. But in terms of the actual writing of the book, I suppose you could say, yes. Walking into that brothel and having the sense of it totally informed the way that I wrote the book and kind of why I wanted to write it the way that I wrote it. I spent a number of days there and was able to physically walk around the space both to pick up the atmosphere and work out the immediate neighbourhood around the brothel. There was the Elephant Inn, and directly opposite there was this other tavern, which, if it has a name, I was not able to find it, so I called it The Sparrow, and this little square that is there.

When I described where they were walking, those were real streets I had actually walked, so that is what I hoped to bring as well to the book. Then, other times that was not the case. Not all of Pompeii is in the same intense state of preservation; some parts of it are more ruinous than others. Even when I invented Pompeii, it was based on things that I remember, little things that I had seen. It was a combination of the immediate environment of the brothel based on the actual physical remains of the site and other stuff like, say, Zoilus' house or Cornelius' house. Those are imaginary places that are based on some of the grander houses that I visited.

Kelly: It must have been so great to have physical things that you could see and walk down to inform the way you write.

Elodie: Honestly, it was amazing.

Kelly: Was it a helpful experience? Did you ever wish that a building was not there?

Elodie: No. In all honesty, when the facts really got in the way of something I wanted to do, I did dispense with the facts, which sounds strange because I was so diligent about my research, and it so permeates the book. I tried 99% of the time to be absolutely accurate, but every now and then there comes a point where you are writing fiction and we just do not know how things would have been done.

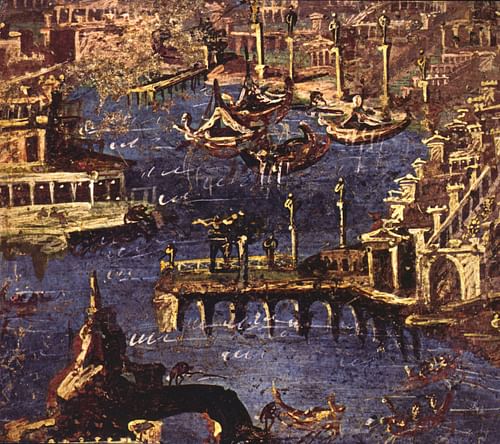

There are a couple of points where I did elaborate or change things slightly. The harbour is based on a fresco of the harbour at Stabiae, which is a nearby ancient 'resort' further up the coast. There is a fresco in the museum at Naples that shows what an ancient harbour along that part of the coastline looked like, something like a mile or so away from Pompeii, which at that point would have been a proper port, much closer to the sea. I tried to base it on that; it is quite an impressionistic sketch. But then I just thought, I want to put a giant column of Venus in the sea. We know there was the Colossus of Rhodes; obviously, it would not have been anything that spectacular or we would have heard about it. But I thought I was going to have a column of Venus to underline to the modern reader that this is Venus' town, which it was. She was the patron deity of Pompeii. So, I stuck it in there; we have no evidence that such a thing existed, I just invented it.

Kelly: The book is a story of fiction, you're allowed to have a creative licence. I really enjoyed reading about the Vinalia, that was such a fascinating festival!

Elodie: Venus was the patron deity of Pompeii but she was also the patron of prostituted women and men, and of love and sex and all these things, and prostitutes were able to participate in certain public festivals in the ancient world. Although it was a very stigmatised way of life in some respects, it was also accepted as part of life. There was the Vinalia, and there was also the Floralia, two particular ceremonies for prostituted women to take part in, and I wanted to reflect that in my book because I felt that for the women in my story, this would be really important.

Ovid wrote a whole book about how Roman festivals were celebrated, including the Vinalia, so we have some evidence. It is quite fragmentary and hard to piece together, so I combined that with a fresco in Pompeii with people carrying a God on a platform in some kind of religious festival and I also thought about Catholic celebrations of the Virgin Mary that still take place in southern Europe and combined all of those things to create my own imaginary version of the Vinalia and what it might have been like. That was a really crucial scene in the book, both in terms of how I reimagined Pompeii and in trying to convey to people that, yes, the women were prostituted and had incredibly hard, difficult, and stigmatised lives, but they were also part of their community in a very particular way, and in a way that is very unfamiliar to us - this idea that there would be a public parade and celebration of prostitutes advertising themselves.

Kelly: This whole book focuses on how these women do not own themselves, their bodies. They do not own anything, and yet they have this time where they can just be out in the open, walking with all these other women that are in exactly the same position that they are, and they know exactly how they feel. I wanted to ask a little bit about your five women. Where did they come from? Are all of their names from graffiti?

Elodie: Cressa, Berenice, and Victoria are all real names from the brothel at Pompeii. We have graffiti that they either wrote or was written about them, and Victoria in particular, she writes about herself in a very particular style. She calls herself Victoria the Conqueress, which, if you read the book, is exactly in keeping with her personality. I particularly wanted to fit the names of the other two, Amara and Dido, with their characters. Amara has a name that was given to her by Felix, the pimp and also the antagonist of the story. It has a very particular meaning, which I am not going to explain, but she talks about that later. Felix is her nemesis, and their relationship is very important all the way through the trilogy. She is very much my own imaginary character. Well, they all are, obviously. We know nothing other than the names of Cressa and Bernice, and little else about Victoria.

I chose Dido because she's from Carthage, and Felix named her as well. I did not include this in the book in the end, but he calls her Dido almost as a cruel joke, calling her the name of a famous queen of Carthage while she is enslaved in a brothel. It is a reflection on his personality that she would have that name. Their personalities are hugely different, and the reason that I did that is that they would not have chosen to all be there together. They would have been very randomly thrown together, no particular connections to one another whatsoever, and they would likely have had very different outlooks, feelings, and beliefs about life.

I wanted to make Amara an outsider, both to the life in the brothel and to Pompeii, because we see the whole place through her eyes. She was sold into slavery, and her family became destitute. That was a totally normal way for people to end up enslaved. But that is where she gets her real fire from; she wants to get out because she has known something else and she wants to get it back. Dido has a really tragic back history in that she was kidnapped - again, completely regular that this happened to people. She is from a little suburb outside Carthage, and people living in those sorts of places were quite vulnerable to pirates or bandits just grabbing them and selling them off. Her experience of the brothel is more traumatic in many ways than any of the other characters. At first, she obviously gains a lot of resilience as it goes on, but they are all very protective of her.

Victoria, Cressa, and Berenice were all born into slavery, but their roots were all very, very different. Berenice is from Egypt, born into slavery, but she comes from a completely different part of the Roman Empire. Cressa is older, she has her own anxieties because of ageing. I saw her as about 10 years older than the other women. And Victoria is this incredibly strong, outspoken woman, unlike the others who all pretty much hate what is happening. Victoria hates it, too, but she has also adapted by becoming "incredibly good" at her job. She is incredibly popular with the customers, she is hugely successful, she makes a lot of money. The pimp really likes her because of the business that she brings, and he calls her his favourite whore. So, her relationship reflects a different attitude to being enslaved, which was just to go for it and embrace that role. I did not want to make too many of the women have Victoria's attitude because I do not know how common this was, although it is very stereotyped in stories about prostitution.

Kelly: I think it makes it more believable, and to have one of them acting in such a different way is really important. I definitely feel like your book and these women have made it really clear to people that women in the ancient world were not necessarily always living this life.

Elodie: Also, one of the things that was really key for me while writing the book was that we know it is set in a brothel, it is obvious. I had no need to dwell on the sex work, I did not describe graphic scenes, I did not want that to be the focus of the story. We know that this is going on in their lives and some of them have adapted and made the best of it while others are profoundly traumatised by it. There are other ways of conveying that. What I wanted to talk about was all the other aspects of their lives. Exactly as you say, they were people.

They have their own stories, their own families. They grew up in different ways, their own expectations of life, their own hopes their own relationships. For them, life would not have been all about sex. They would have had their fun and enjoyment and hopes in other areas when they go out strolling around town together. Yes, to pick up business, but also just to have a bit of a break when they go to the baths and it is an all-female environment. They can have a gossip and they can hang out. They go to the tavern and they are friendly with the innkeeper; not every man in this story is awful. I did not want it to be a tragic tale where everything is just awful, and I also did not want it to be about giggling girls. Those two things are the cliched tropes of talking about brothel life; I wanted neither.

Kelly: In reality, it probably would have been a combination of both. They would have still lived their lives as best as they could while still having to do this job. So, we have talked about the women in the book. Do you want to tell us a little bit about the main male characters? Where do they come from, and how did they develop?

Elodie: Felix and Paris are also names found in the brothel, and Paris in particular, who is referred to as "beautiful Paris", was almost certainly working in the brothel. Although it is very much from a female point of view, the thing that struck me both in the research and writing the book was also how very little agency so many men also had. Paris is not the most sympathetic character at all, but I found him very poignant because he has not got any of the camaraderie of the women, both because he rejects them and because he just does not fit. He is in such a stigmatised role as a man who has to perform sex for other men. That surprised me, too, in the sense that before researching this I thought, well the ancient Romans were not homophobic. They had these idealised gay relationships, but, actually, it is all about power dynamics in their view of sex and relationships.

The person who does not have power, which is automatically the woman in a male-female relationship, is always lesser. When two men get together outside this very idealised stereotype of the younger guy and the older man, the guy who has the least power is horribly stigmatised. Paris neither can have the friendship with the women and belong with them nor can he have the respect of the other men who work in this kind of slightly gangster-style brothel organisation. His loneliness, I felt, was quite key.

Felix, who is the pimp, starts off pretty monstrous, but I really did not want him to be that way. As the book goes on, we can see the similarities between Felix and Amara, the fact that there may actually have been some similarities in their background, but also that they are two people who have found themselves in survive-or-die situations. And in that case, you might have to make some pretty terrible choices and do some terrible things. Amara's capacity for doing things that are not so nice develops as the book carries on, and we understand that she is much more like Felix than perhaps either of them had grasped. Also, that perhaps then that may or may not make Felix more like Amara, which makes him more sympathetic.

In terms of the relationship Amara later has with the wealthy patron who she sees as a way out, I wanted that storyline in some ways to be a kind of anti-Pretty Woman. I wanted to interrogate whether it is ever possible, even when somebody is nice and seems to be on a white horse, in a relationship where one has all the power, quite literally in that case, in that he is free and she is not, and he has the power to buy her. Is it possible for her to love him or even know if she loves him when what she needs from him is so huge and what he can take from her is kind of nothing to him?

Kelly: It was very conflicting, which was so fascinating. I think it definitely added an extra layer to the whole story that none of these people had a choice, regardless of whether they have the power or not. No one is all good or bad, and I think that there was a lot of moral greyness about the characters and about the whole story in general, which I thought was important. Just because they have been sold as prostitutes, it does not mean that they are necessarily 100% good people, and the guy who does the pimping out is not necessarily all bad. Thank you so much for joining me today!

Elodie: Thank you so much for having me! It has been a real pleasure.