Raising sugar cane could be a very profitable business, but producing refined sugar was a highly labour-intensive process. For this reason, European colonial settlers in Africa and the Americas used slaves on their plantations, almost all of whom came from Africa. If they survived the horrific conditions of transportation, slaves could expect a hard life indeed working on plantations in the Atlantic islands, Caribbean, North America, and Brazil.

The plantation system was first developed by the Portuguese on their Atlantic island colonies and then transferred to Brazil, beginning with Pernambuco and Sâo Vicente in the 1530s. With most of the workforce consisting of unpaid labour, sugar plantations made fortunes for those owners who could operate on a large enough scale, but it was not an easy life for smaller plantation owners in territories rife with tropical diseases, indigenous populations keen to regain their territories, and the vagaries of pre-modern agriculture. Nevertheless, the plantation system was so successful that it was soon adopted throughout the colonial Americas and for many other crops such as tobacco and cotton.

Madeira & the Plantation System

In the 15th century, it was the Portuguese who first adapted a plantation system for growing sugar cane (Saccharum officinarum) on a large scale. The idea was first tested following the Portuguese colonization of Madeira in 1420. Madeira, a group of unpopulated volcanic islands in the North Atlantic, had rich soil and a beneficial climate for growing sugar cane all year round. The Portuguese Crown parcelled out land or ‘captaincies’ (donatarias) to noble settlers, much like they did in the feudal system of Europe. These nobles in turn distributed parts of their estate called semarias to their followers on the condition that the land was cleared and used to grow first wheat and then, from the 1440s, sugar cane, a portion of the crop being given back to the overlord. The project was financed by Genoese bankers while technical know-how came from Sicilian advisors. It was from Sicily that the various varieties of sugar cane were brought to Madeira.

Sugar from Madeira was exported to Portugal, to merchants in Flanders, to Italy, England, France, Greece, and even Constantinople. By the end of the 15th century, the plantation owners knew they were on to a good thing, but their number one problem was labour. Consequently, slaves were imported from West Africa, particularly the Kingdom of Kongo and Ndongo (Angola). The scale of human traffic was relatively small, but the model was now in place that would be copied and refined elsewhere following the Portuguese colonization of the Azores in 1439, the Cape Verde Islands (1462), and São Tomé and Principe (1486).

São Tomé and Principe were really the first European colonies to develop large-scale sugar plantations employing a sizeable workforce of African slaves. The system was then applied on an even larger scale to the new colony of Portuguese Brazil from the 1530s. Within a few decades, Brazil had become the world’s largest producer of sugar. The same system was adopted by other colonial powers, notably in the Caribbean. As the historian M. Newitt notes,

Here [São Tomé and Principe] the plantation system, dependent on slave labour, was developed and a monoculture established, which made it necessary for the settlers to import everything they needed, including food. Sâo Tomé took on all the characteristics later assumed by the islands of the Lesser Antilles; it was a Caribbean island on the wrong side of the Atlantic. (61)

The Manufacturing Process

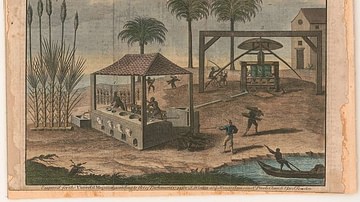

The sugar cane industry was a labour-intensive one, both in terms of skilled and unskilled work. Fields had to be cleared and burned with the remaining ash then used as a fertilizer. Sometimes land had to be terraced, although not usually in Brazil. Irrigation networks had to be built and kept clear. A great number of planters and harvesters were required to plant, weed, and cut the cane which was ready for harvest five or six months after planting in the most fertile areas. As cane was planted each month in one part of a plantation, the harvesting was an ongoing process for much of the year, with the more intense periods requiring slaves to work night and day. Carts had to be loaded and oxen tended to take the cane to the processing plant. The sugar then had to be packed and transported to ports for shipping.

All of the above tasks could be done by unskilled labour and were done mostly by slaves and a minority of paid labourers. The real problem was the process of producing sugar. As the historian A. R. Disney notes, "sugar production was one of the most complex and technologically-sophisticated agricultural industries of early modern times" (236).

Machinery had to be built, operated, and maintained to crush and process the cane. On early plantations, hand-presses were used to crush the cane, but these were soon replaced by animal-powered presses and then windmills or, more often, watermills; hence plantations were usually located near a stream or river. To save transportation costs, plantations were located as near as possible to a port or major water route. Those plantation owners who could not afford their own mill plant used those of the larger concerns and paid a percentage of the resulting crop for the privilege. A mill plant needed anywhere from 60 to 200 workers to operate it. In addition, the refineries needed a great deal of timber as fuel for their furnaces, and providing it was another laborious task for the plantation’s slaves. Those with the skills to operate and maintain the machinery in sugar mills were much in demand, especially their chief supervisor, the sugar master, who enjoyed a high salary. Over time, as the populations of colonies evolved, mixed-race European-locals, freed slaves, and sometimes even slaves were employed in these technical positions.

The cut cane was placed on rollers which fed it into a crushing machine. The juice from the crushed cane was then boiled in huge vats or cauldrons. The liquid was then poured into large moulds and left to set to create conical sugar 'loaves', each 'loaf' weighing 15-20 lbs (6.8 to 9 kg). The refined sugar then had to be dried thoroughly if it was to be as white and pure as the top merchants demanded. This necessity was sometimes a problem in tropical climates. Sugar of lesser quality with a brownish colour tended to be consumed locally or was only used to make preserves and crystallised fruit. The cane leftovers from the whole process were usually given to feed pigs on the plantation.

The Life of a Plantation Slave

Slaves could be acquired locally but in places like Portuguese Brazil, enslaving the Amerindians was prohibited from 1570. Most plantation slaves were shipped from Africa, in the case of those destined for Portuguese colonies, to a holding depot like the Cape Verde Islands. Here they were given a number of basic lessons in Portuguese and Christianity, both of which made them more valuable if they survived the voyage to the Americas. These lessons also eased traders’ consciences that they were somehow benefitting the slaves and giving them the opportunity of what they considered eternal salvation.

Brazil was by far the largest importer of slaves in the Americas throughout the 17th century. When Brazilian sugar production was at its peak from 1600 to 1625, 150,000 African slaves were brought across the Atlantic. One in five slaves never survived the horrendous conditions of transportation onboard cramped, filthy ships. The voyage to Rio was one of the longest and took 60 days. Once at the plantation, their treatment depended on the plantation owner who had paid to have them transported or bought the slaves at auction locally. It was not uncommon to give new arrivals a whipping just to show them, if they had not already realised, that their owners had no more sympathy for their situation than the cattle they owned. Slaves were thereafter supervised by paid labour, usually armed with whips. A watchtower was a feature of many plantations to ensure work schedules and rates were kept and to guard against external attacks.

Slaves had to learn the local pidgin such as creole Portuguese in Brazil. They typically lived in family units in rudimentary villages on the plantations where their freedom of movement was severely restricted. In many colonies, there were professional slave-catchers who hunted down those slaves who had managed to escape their plantation.

Slaves lived in simple mud huts or wooden shacks with little more than matting for beds and only rudimentary furniture. Some owners permitted marriages between slaves - formal or informal - while others actively separated couples. A problem for all male slaves was the fact that there were far more of them than females brought from Africa. On Portuguese plantations, perhaps one in three slaves were women, but the Dutch and English plantation owners preferred a male-only workforce when possible.

Slaves were permitted at weekends to grow food for their own sustenance on small plots of land. Food raised by slaves included manioc, sweet potatoes, maize, and beans, with pigs kept to provide occasional meat. The diet was unvaried and meant to be as cheap for the owner as possible. The lack of nutrition, hard working conditions, and regular beatings and whippings meant that the life expectancy of slaves was very low, and the annual mortality rate on plantations was at least 5%.

The Life of a Plantation Owner

Plantation owners obviously had a much better life than the slaves who worked for them, and if successful in their estate management, they could live lives far superior to anything they could have expected back in Europe. With household slaves and personal attendants, the wealthiest white Europeans could afford a life of ease surrounded by the best things money could buy such as a large villa, the finest clothing, exotic furniture of the best materials, and imported artworks by Flemish masters. With profits at only around 10-15% for sugar plantation owners, most, however, would have lived more modest lives and only the owners of very large or multiple estates lived a life of luxury. This latter group included those who lived in towns and not on their plantations, nobles who never even visited the colony, and religious institutions. It is also true that, just as with farming today, most of the profits in the sugar industry went to the shippers and merchants, not the producers. Finally, states imposed taxes on sugar. In short, ownership of a plantation was not necessarily a golden ticket to success.

There were some serious problems, then, to be faced by plantation owners. There were the challenges of growing any kind of crops in tropical climates in the pre-modern era: soil exhaustion, storm damage, and losses to pests - insects that bored into the roots of sugarcane plants were particularly bothersome. A large capital outlay was required for machinery and labour many months before the first crop could be sold. Food crops had to be grown to feed the paid labour, technicians, and the owner’s family. Another constant worry was unfamiliar tropical diseases which often proved fatal with the colonists, and particularly new arrivals. All of these factors conspired to create a situation where plantations changed ownership with some frequency.

Another major risk to the sugar planters was rebellions by the slaves. Although slaves had only tools as potential weapons, there was usually no centralised military presence to aid plantation owners who often had to rely on organising militia forces themselves. There were many instances of slave uprisings resulting in the deaths of the plantation owner, their family, and slaves who had remained loyal to their owner. Wars with other Europeans were another threat as the Spanish, Dutch, British, French, and others jostled for control of the New World colonies and to expand their trade interests in the Old one.

Then there were the indigenous people who might have been subdued by initial military campaigns but, nevertheless, remained in many places a significant threat to European settlements. At the same time, local populations had to be wary of regular slave-hunting expeditions in such places as Brazil before the practice was prohibited. The clash of cultures, warfare, missionary work, European-born diseases, and wanton destruction of ecosystems, ultimately caused the disintegration of many of these indigenous societies. Sugar and the people who reaped its profits, like many industries before and since, caused massive disruption and destruction, changing forever both the people and places where plantations were established, managed, and all too often abandoned.

Learn more on the geographical spread of the colonial sugar plantation system in our article Sugar & the Rise of the Plantation System.