The Tale of The Ship-Wrecked Sailor is a text dated to the Middle Kingdom of Egypt (2040-1782 BCE). It is a story of adventure whose purpose, besides entertainment, would have been to impress upon an audience how all one needed to be content in life was found in Egypt.

The name of the author, and even its point of origin, are unknown. According to scholar Miriam Lichtheim:

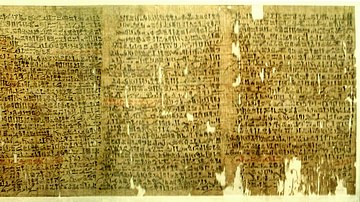

The only preserved papyrus copy of the tale was discovered by Glenischeff [a scholar] in the Imperial Museum of St. Petersburg. Nothing is known about its original provenience. The papyrus, called P. Leningrad 1115, is now in Moscow. The work, and the papyrus copy, date from the Middle Kingdom. (211)

Contemporary with the rise of the Cult of Osiris and the inscribing of the Coffin Texts, The Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor tells a similar story of redemption. The Coffin Texts were inscribed on the walls of tombs c. 2134-2040 BCE while the Cult of Osiris had been gaining in popularity since at least the latter part of the Early Dynastic Period (c. 3150-c. 2613 BCE) to become the most popular and influential religious and cultural belief by the time of the New Kingdom (c. 1570-c. 1069 BCE). The concept of redemption, of death from life, features as prominently in this piece of literature as in the Osiris Myth and the Coffin Texts.

The ancient Egyptians believed in the cyclical nature of life - that which dies returns again - but in two distinct forms. The traditional belief of the Egyptians was that a person died and went on to The Field of Reeds, a paradise which was a mirror image of the life they had known on earth. The other understanding of the nature of life and death came to be known famously as The Transmigration of Souls popularized by the Greek philosopher Pythagoras and, even more so, by Plato. In The Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor there is no death and resurrection but the theme of an individual becoming lost in a strange and frightening land and then returning home is central and this would have resonated with an ancient Egyptian audience.

The Story

The basic form of the story is very simple: an official of the king returns home from a venture which did not go well. He has to report the bad news to the king and is obviously worried about what might happen to him at the meeting. His servant, trying to cheer him up, tells him a story of something which once happened to him. The servant, who was once a sailor, tells of his own expedition which was a complete failure, much worse than that which his master has experienced, but led to a great adventure.

He tells his master how he survived the shipwreck and came ashore on an amazing island where he met a great talking serpent who called himself the Lord of Punt. All good things were on the island and the sailor and the snake converse until a ship is hailed and he can return to Egypt. As the Land of Punt had been a well-known partner in trade with Egypt since the Fourth Dynasty (c. 2613-2498 BCE) it is interesting to see it portayed mythically as an island of riches and magic from which the sailor is rescued, after being helped by the serpent, and returned home a richer man.

On a surface level, the story may be read as simple comedy. The master has suffered a poor business transaction and his servant tries to cheer him by telling a fabulous story which the master is not at all interested in hearing. The master comes just short of telling the servant to go away. When the master says, "Do as you wish; it is wearying to talk to you" it is the ancient equivalent of the modern day "Whatever".

The sailor insists on telling his tale, however, and the master indulges him. However entertaining the story may be, it does not seem to lighten the master's mood any. In the end, the master says "Do not continue, my excellent friend. Does one give water to a goose at dawn that will be slaughtered during the morning?" Here he is telling the servant that there is no point trying to console someone who is going to his fate. The colophon at the end is the signature of the scribe who wrote, or more likely copied, the piece.

Cultural Significance

One of the most interesting aspects of the story is how perfectly it reflects Egyptian culture in any stage of its development. The Egyptians loved their land so completely that they fashioned their afterlife as a perfect reflection of it. The reason why there are no accounts of great Egyptian sea travelers or why there is no `Egyptian Herodotus' or `Egyptian Homer' is because the Egyptians did not like to leave their native land. Throughout the entire history of Egypt there are only military campaigns to the nearest regions such as Syria, Palestine, and Nubia.

There was never an Egyptian empire on par with that of Assyria or Rome because the Egyptians simply did not care about what went on in other regions. The Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor reflects this in that the sailor is not off on some grand adventure when he finds the island; he is just going about his business when a storm sinks his vessel and casts him up on the shores. He never thinks of staying on the magical island, nor is he tempted by what he finds there, because he knows that his home back in Egypt holds all of the earthly treasures he is interested in.

This same love of the homeland is reflected in many of the literary works which were most popular with the ancient Egyptians. In The Story of Sinuhe, which was a best-seller in its time, Sinuhe finds himself exiled in a foreign land and one of his most pressing concerns is dying beyond Egypt's borders. He laments, "What is more important than that my corpse be buried in the land in which I was born!" For the Egyptians, one went to sea for trade, for one's business, but there was nothing beyond Egypt's boundaries which could possibly be more satisfying than what one could find at home; not even the alluring and fabulously wealthy Land of Punt.

The Land of Punt became the most important partner in trade during the reign of Queen Hatshepsut (1479-1458 BCE). From the Early Dynastic Period (c. 3150-c. 2613 BCE) through Hatshepsut's reign Punt was referenced as the "land of plenty" which supplied Egypt with many of its most important goods. The 1493 BCE expedition sent by Hatshepsut brought back gold and ivory as well as thirty-one live incense trees for transplant.

This is the first recorded transplant of foreign fauna in history. Scholars continue to debate on where the Land of Punt actually was or what it has become even though it seems clear that modern-day Somalia holds the strongest claim for the honor. After Hatshepsut, Punt steadily receeded in Egytian imagination until it became a semi-mythical land which eventually came to be seen as the origin of Egyptian culture and the land of the gods.

While it may be tempting to speculate that The Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor was the beginning of this process, the story was written long before Hatshepsut's reign during which it is detailed clearly as an actual region and partner in trade. It is interesting, however, to see Punt depicted so early as a "magical island" and the Lord of Punt as a gigantic talking serpent.

There are many comedic elements throughout the story - not least of which are the responses by the long-suffering master - but as nothing is known of the origin of the tale or the ancient response to it one cannot tell how it was recieved by an Egyptian audience. One can imagine, however, they enjoyed it just as much as any modern audience would; the love of a good story told well is ageless.

The Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor

The following translation of the text is from W.K. Flinders Petrie, 1892:

Speech of an excellent follower:

May your heart prosper, my master. Behold, we have reached home. The mallet having been taken, the mooring post is driven in. The bow-rope having been placed on land, thanksgiving and praise to god are given. Everyone is embracing his companions. Our crew returned safely; there was no loss to our army. We have reached the end of Wawat; we have passed Senmut.

Behold, we have come in peace, our land we have reached.

Listen to me, O master, I am free of excess. Wash yourself, give water to your hands, so that you may answer the king when you are addressed and may speak to the king sensibly and may answer without stammering in telling this tale. A man's mouth rescues him. He speaks and causes one to show indulgence.

Do as you wish; it is wearying to talk to you, my master said to me.

Nevertheless, let me tell you the like thereof, it having happened to me, myself.

I was going to the mine of the king. I went down to the sea in a ship of one hundred twenty cubits in length and forty cubits in width. One hundred twenty sailors were in it of the choicest of Egypt. Whether they looked at the sky or they looked at the land, their hearts were braver than lions. They could foretell a storm before it came, foul weather before it occurred.The storm came while we were on the sea, before we approached the land. While we were sailing it made a continuous howling, raising a wind. Waves were in it of eight cubits. A piece of wood struck it for me.

Then I was cast upon an island by a wave of the sea. I spent three days alone, my heart as my only companion. Resting in the shelter of a tree, I embraced the shade.

Then I stretched out my legs to know what I could place in my mouth. I found figs and grapes there. Leeks were ruler there. Sycamore figs were there together with notched Sycamore figs. Cucumbers were there as though cultivated. Fish were there together with birds. There was nothing that was not within it.

Then I satisfied myself and I placed some of it on the ground because it was too much upon my hands. I took a fire drill and made fire and made a sacrifice.

And then I heard the voice of a storm or the hungry voice of the raging storm stike! What was it moving quickly, fast approaching, landing right before me. I thought that it was a wave of the sea or people taking refuge from the waves in the mouth of the channel. Trees broke and the earth shook. What is this in the water? Facing the division of the breakers I crouched, as it was quickly coming and approaching quickly. I covered my face; we are found.

I uncovered my face and found that it was a snake that was coming. It was thirty cubits long. His beard, it was greater than two cubits long. His body was overlaid with gold. His eyebrows were real lapis lazuli. He was bent up in front. He opened his mouth to me while I was on my belly in his presence. He said to me, "Who brought you? Who brought you, commoner, who brought you? If you fail to tell me who brought you to this island I will cause you to know yourself, you being as ashes having become as one who is not seen.”

You are speaking to me, but I do not hear it. I am in your presence but I am ignorant of myself.

Then he placed me in his mouth and took me to his dwelling, his place of happiness, and set me down untouched, I being uninjured, nothing being taken from me. He opened his mouth to me while I was on my belly in his presence.

Then he said to me, "Who has brought you, Who has brought you, commoner? Who has brought you to this island in the sea whose sides are in the water?"

Then I answered him this, my arms bent in respect in his presence. I said to him, "I was going to the mine of the king in a ship of one hundred twenty cubits in length and forty cubits in width. One hundred twenty sailors were in it of the choicest of Egypt. Whether they looked at the sky or whether they looked at land, their hearts were braver than lions. They could foretell a storm before it came, foul weather before it occurred. Every one of them, his heart was braver, his arm stronger, than his companions. There was none ignorant in their midst. The storm came while we were on the sea, before we approached the land. While we were sailing it made a continuous howling. Waves were in it of eight cubits. A piece of wood struck it for me. Then the boat died and of those in it not one remained therein, except me. Behold, I am at your side. Then I was cast upon this island by a wave of the sea."

He said to me, "Do not fear, do not fear, commoner. Do not blanch your face since you have reached me. Behold, it is god who caused you to live, he brought you to this island of ka. There is nothing that is not within it; it is filled with all good things. Behold you shall do month upon month until you complete four months from home on this island. A ship will come from home with sailors in it whom you know. You will go home with them and you will die in your city. Happy is he who tells what he has tasted, a painful thing having passed by. Let me tell you the like there of which occurred on this island in which I was on it with my brothers, and children were in the midst of them. We totaled seventy-five snakes, my children together with my brothers; I will not mention to you a little daughter whom I had obtained by prayer. Then a star fell, and these went up in flame because of it. It happened that I was not with them when they burned. I was not among them. I was dead to them and would have died for them when I found them a heap of corpses all together. If you are strong, subduing your heart, you will fill your embraces with your children, you will kiss your wife, you will see your house. It is more beautiful than anything. You will reach the residence of your homeland in which you were in it together with your companions.”

Having stretched out on my belly, I touched the ground in his presence. I said to him, “I will speak of you, I will relate your power to the king, I will cause him to know of your greatness. I will cause to be brought to you laudanum heknu oil, yudenbu, hesayt spice, incense of great temples which pleases all of the gods in it. I will relate what has happened to me, what I saw of his power. One will praise god for you in the city before the magistrates of the entire land. I will slaughter for you bulls as sacrifices. I will offer to you fowl. I will cause to be sent to you ships loaded with the provisions of every town in Egypt, as is done for a god who loves a people in a distant land not known to the people.”

Then he laughed at me for what I said was foolishness to him. He said to me, "You are not rich in myrrh being an owner of incense. It is I who am the lord of Punt and the myrrh, it belongs to me. And the incense that you spoke of bringing, it is abundant on this island. When it happens that you leave this place, it will not occur that you will see this island again, it having become water."

Then, in time, that boat came like what he had predicted before hand. Then I went and placed myself in a high tree and I recognized those in it. Having gone to report it, I found that he knew it. Then he said to me,

"Health, Health, commoner, to your house so that you may see your children. Make my name good in your town, that is my due from you."

Then I placed myself upon my belly my arms bent in respect before him. Then he gave to me a quantity of myrrh, heknu oil, laudanum, hesayt spice, tishpes spice, perfume, eye-paint, giraffes' tails, great lumps of incense, elephants' tusks, greyhounds, monkeys, baboons and all kinds of precious things. Then I loaded them upon this boat. It happened as I placed myself on my belly to give thanks to him that he said to me, "Behold, you will approach home in two months. You will be full, you will embrace your children, you will be young in the home where you will be buried."

Then I went down to the river bank in the neighborhood of this boat. Then I called to the sailors who were in this boat. I gave praise upon the bank to the lord of this land, and those in it did likewise. It was a sailing which we did downstream to the palace of the king. We approached the residence after two months which he had said completely. Then I entered in before the sovereign and I brought to him the gifts which I had brought out of this island. Then he gave praise to me before the magistrates of the land to its ends. Then I was made a follower and I was endowed with two hundred people. See me after I returned to the land after I saw what I tasted. Listen to my mouth; it is good for people to listen.

Then my Master said to me, "Do not continue, my excellent friend. Does one give water to a goose at dawn that will be slaughtered during the morning?"

It is done from its beginning to its end, as it was found in writing, a scribe excellent with his fingers, Imenyâs son Imena.