Finding a maritime route to the East and gaining access to the lucrative spice trade stood at the root of the European Age of Exploration. However, when Vasco da Gama rounded the Cape of Good Hope and reached the Indian Ocean in 1493, he found a vibrant international trade network already in place, whose expanse and wealth was well beyond European imagination.

Three powerful Muslim empires ringed the Indian Ocean. The Ottoman Empire in the west occupied the territory once held by the Byzantine Empire and controlled the Red Sea trade route linking Southeast Asia with Venice. In the center was the Safavid Dynasty, who controlled the Persian Gulf Route. In the East was the Mughal Empire, covering most of India but still contending with powerful Hindu governments including the Kingdom of Kozhikode (Calicut) and the Vijayanagara Empire in Southern India. Sri Lanka (Ceylon) was ruled by Buddhists.

There were two major Muslim portals to the Indian Ocean. The Ottoman’s portal was through Aden, at the opening of the Red Sea. Aden’s history as a key Red Sea link with the Indian Ocean went all the way back to antiquity and the Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans. Now a well-fortified Arab Muslim enclave, all trade goods from the Indian Ocean found their way to Aden for shipment to Egypt. The Safavid portal to Indian Ocean trade was at Hormuz between the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman, and it had long served as a vital link between the Persian world and the Indian Ocean.

India at the Center

India was at the center of the Indian Ocean trade for centuries. Among the most important mercantile cities were Hindu-controlled Calicut (Kozhikode), Cannanore, Cochin, Quilon, and Muslim Goa along the southwestern Malabar Coast, and Muslim-controlled Cambay of Gujarat in the northwestern corner of the peninsula. By the end of the 15th century, Gujarat sailors were rivaling the Arabs as dominant traders across the Indian Ocean.

Calicut was by far the most important trading center of India and was the world’s number one source of pepper. For centuries it was a primary destination of all Indian Ocean traders from Aden, Ormuz, Malacca, and China. It also came to be renowned for what the European traders called “calico” cloth, from which it derived its English name.

Cambay in Gujarat was the home to who came to be the world’s most widely traveled sailors. As 16th-century chronicler Tome Pires observed:

There is no doubt that these people have the cream of the trade. They are men who understand merchandise; they are so properly steeped in the sound and harmony of it, that the Gujaratees say that any offence connected with merchandise is pardonable. There are Gujaratees settled everywhere. They work some for some and others for others. They are diligent, quick men in trade. They do their accounts with figures like ours and with our very writing. They are men who do not give away anything that belongs to them, nor do they want anything that belongs to anyone else; wherefore they have been esteemed in Cambay up to the present......

Cambay chiefly stretches out two arms, with her right arm she reaches out towards Aden and with the other towards Malacca, as the most important places to sail to….. They sail many ships to all parts, to Aden, Ormuz, the kingdom of the Deccan, Goa, Bhatkal, all over Malabar, Ceylon, Bengal, Pegu, Siam, Pedir, Pase (Paefe) and Malacca, where they take quantities of merchandise, bringing other kinds back, thus making Cambay rich and important. (Cortesão, 42)

By the 15th century, the key ports of the vast Indian Ocean trading network were under mostly Muslim control. Muslim traders had spread far and wide from Arabia, settling in mercantile communities across Africa, India, Sri Lanka, Indonesia, and Southeast Asia. As the Muslim communities grew strong, they became trading empires led by powerful sultans. These included Malacca on the Malaya Peninsula, the islands of Ternate and Tidore in the Moluccas, and a series of rich city-states that stretched along the coast of East Africa.

Swahili Coast of Africa

The series of rich Muslim-controlled city-states spanned from Sofala (in today’s Mozambique) in the south to Mogadishu (in modern Somalia) in the north. In between were Mombasa, Gedi, Pate, Lamu, Malindi, Zanzibar, and Kilwa. The social structure of the Swahili city-states was a complex of native African and mixed Arab-African blood. According to the historian H. Neville Chittick:

The inhabitants of the towns could be considered as falling into three groups. The ruling class was usually of mixed Arab and African ancestry … such also were probably the landowners, merchants, most of the religious functionaries and the artisans. Inferior to them in status were the pure-blooded Africans, probably mostly captured in raids on the mainland and in a state of slavery, who cultivated the fields and no doubt carried out other menial tasks. Distinct from both these classes were the transient or recently settled Arabs, and perhaps Persians, still incompletely assimilated into the society. (Fage, 209)

The most powerful of the African states on the eastern coast were Mombasa and Kilwa, followed by Malindi. They traded ivory from the south, gold and slaves from the western interior and frankincense and myrrh from northern Africa. Kilwa and Mogadishu also produced their own textiles for sale and extracted copper from nearby mines. All of the states produced pottery and iron objects for both local use and trade. The international merchants traded with them mostly cotton, silk, and porcelain.

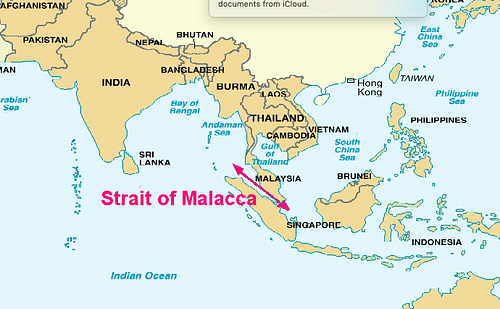

Malacca

As the 16th century dawned, the city of Malacca (Melaka) on the Malay Peninsula had also become a center of world trade. It was located at the narrowest point of the Strait of Malacca and was accessible in all seasons. Malacca became the major clearinghouse for all of the spices produced across Indonesia. It was the commonest point of contact between the East and West and linked all the major Indian Ocean trading communities. It became the main trade connection between the Indian Ocean and the South China Sea, and almost all east-west trade passed through this narrow strait, creating rich trade kingdoms on its shores. As Tomé Pires tells it:

Malacca is a city that has been built for trade, higher than any other in the whole world, at the end of monsoons and beginning of others. Malacca is surrounded and stands in the middle, and receives trade and commerce from a large spectre of nations, a thousand leagues from each side. (Cortesão, 45)

Sailors from all across the Indian and China seas converged in Malacca to trade pepper, cloves, nutmeg, and mace, and it became a major urban center filled with many residential communities of internationals, among them Indian, Chinese, and Javanese. Among the most prevalent were the Gujarat from Cambay. As Tomé Pires further relates:

There were a thousand Gujarat merchants in Malacca, besides four or five thousand Gujarat seamen, who came and went. Malacca cannot live without Cambay, nor Cambay without Malacca, if they are to be very rich and very prosperous. All the clothes and things from Gujarat have trading value in Malacca and in the kingdoms which trade with Malacca; for the products of Malacca are esteemed not only in this [part of the ] world, but in others, where no doubt they are wanted…… If Cambay were cut off from trading with Malacca, it could not live, for it would have no outlet for its merchandise. (Cortesão, 45).

Sri Lanka

An important stopover for merchants on the way to and from Malacca was Buddhist Sri Lanka (Ceylon), where the world's finest cinnamon could be obtained along with gems, pearls, ivory, elephants, turtle shells, and cloth. Ships from all across the world came to Sri Lanka for its native products and goods brought from other countries for re-export. The islanders also sent their own ships to foreign ports. The most important items imported were horses from India and Persia, and from China came gold, silver, and copper coins, silk, and ceramics.

Sri Lanka held a key strategic position in the Indian Ocean between East and West, being located next to India and along the sea routes that connected the Mediterranean and Middle Eastern worlds with East Asia. There were numerous bays and anchorages dotted along the coast of Sri Lanka, which provided calm harbors and facilities for ships. At the end of the 15th century, the most important port city was Colombo, filled with Muslims who had settled down in this country to carry on trade activities. Three bitter rival kingdoms ruled Sri Lanka, all under the protection of China through the tribute system.

Spice Islands

At the far eastern terminus of the Indian Ocean trade network in the East Indian archipelago were the Moluccas or Spice Islands from whence came cloves, nutmeg, and mace. Though far from the main trade routes supplying China, India, Persia, Arabia, and Africa, these tiny islands were the only place on earth where these commodities could be obtained.

The earliest mention of the Banda Islands is found in Chinese records dating as far back as 200 BCE. Banda was never settled by Muslim traders, and its trade was controlled by a small group of what the Indonesians called orang kaya or "rich men". Before the arrival of the Europeans, the Bandanese had an active and independent role in trade. They carried their cloves in outrigger canoes to Malaysia and the larger islands of Indonesia for trade with Chinese and Indian mariners.

Muslim traders arrived in Ternate and Tidore in the early 1500s, and by the end of the century rival sultanates had emerged on the two islands that fought over supremacy in the nutmeg trade with the Chinese and Indonesians. They became bitter rivals who wasted much of the great wealth they amassed from the clove trade by fighting each other. When the European traders arrived on the islands in the 16th century, they were able to play Ternate off against Tidore, to get an edge in the clove trade.

Spice Trade & the Age of Exploration

To most medieval Europeans the spices came from some sort of distant paradise, likely the Garden of Eden. Spices were thought to be in great abundance and would be easy to obtain, if only they could find their source. This belief fueled the European Age of Discovery. It enticed explorers like Christopher Columbus (1451-1506) and Vasco da Gama (c. 1469-1524) to embark on their great journeys.

When da Gama rounded the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa, he burst into this vast existing trading network. The European powers were clueless about the depth, sophistication, and wealth of the Indian Ocean trade network. However, they had booming cannons, which they used liberally to take control. Portuguese Cochin was established in 1503, and it was soon followed by Portuguese Goa, which became the capital of the Estado da India, the eastern part of the Portuguese Empire, stretching from Africa to Japan at its height.