As the 15th century ended, Europeans were still mostly in the dark about the Eastern world. Early travelers like Marco Polo had given the West tidbits of information, but these accounts were too highly colored and fragmentary to provide a true picture of Asia. The first really accurate and detailed reports came out in the 1500s from four remarkable travelers - Tomé Pires, Garcia de Orta, Jan Huygen van Linschoten, and Ralph Fitch.

Tomé Pires

Much is known about early sixteenth-century trade in the Indian Ocean and Southeast Asia because of the in-depth report written by Tomé Pires for Manuel I of Portugal between 1512 and 1515. Remarkably, it was left unpublished and lost in the Bibliothèque de la Chambre des députés in Paris until 1944, when it was discovered by historian Armando Cortesão and translated. In this masterpiece, Suma Oriental, Pires describes his journey from Egypt to the Malay Archipelago and provides a detailed historical and ethnographic account of the Indian Ocean emporium trade.

In his introduction, Pires states:

The Suma Oriental is divided into four parts or Suma. books'; the first will deal with the beginning of Asia, starting from Africa to the First India; the second will be from the First India to the end of Middle India; the third will be the High India on the other side of the Ganges, ending at Ayuthia Odia) the fourth will be about the kingdom of China and all the provinces subject to it, with the noble island of Liu Kiu (Lequeos), Japan (Janpon), Borneo, the Lufoes and the Macassars Macaceres) the fifth will be about all the islands in detail [Indonesia].

(Cortesão, 1944, p. 4)

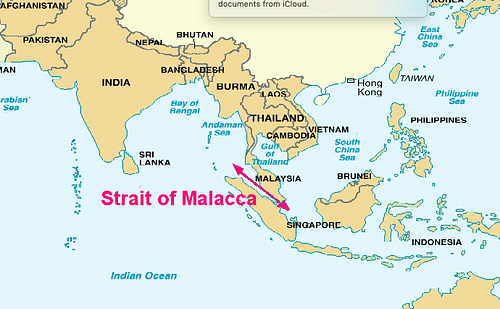

Pires arrived in Portuguese Cochin (Kochi), India in 1511 after stopovers in Aden at the mouth of the Red Sea and Ormuz at the southern end of the Persian Gulf. Little is known of his early life, although he might have been a second-generation apothecary to the royal family. His first job in India was as ‘factor of drugs’ in Cochin but was soon sent to Malacca. Malaysia as a registrar. From there he visited Java, Ceylon (Sri Lanka), the Moluccas (Spice Islands) and ultimately was sent to China where he died in 1524 in a failed diplomatic mission.

Pires left us with vivid descriptions of the major points of trade in the Indian Ocean. It is the first description of the Malay Archipelago and the trade network stretching east all the way to Japan. It is a remarkable compilation of the trade activities including historical, geographical, ethnographic, economic and commercial information. Through its pages one can follow the entire complex trading network that crisscrossed the Indian Ocean.

The central role of trade in the Indian Ocean was abundantly clear to Pires. As he describes in his preface:

And in this Suma I shall speak not only of the division of the parts, provinces, kingdoms and regions and their boundaries, but also of the dealings and trade that they have with one another, which trading in merchandise is so necessary that without it the world would not go on. It is this that ennobles cities that brings war and peace.

(Cortesão, 1944, p. 4)

Tomé Pires describes Cambay in the Gujarat Province in northwestern India as central to the Indian trade network. It was the home to what came to be the world’s most widely travelled sailors. As he observed:

There is no doubt that these people have the cream of the trade. They are men who understand merchandise; they are so properly steeped in the sound and harmony of it, that the Gujaratees say that any offence connected with merchandise is not pardonable. There are Gujaratees settled everywhere. They work some for some and others for others…Cambay chiefly stretches out two arms, with her right arm she reaches out towards Aden and with the other towards Malacca, as the most important places to sail to…

(Ibid, p. 42)

Garcia de Orta

Records of how spices were grown and processed in ancient Southeast Asia were left to us in Garcia de Orta’s remarkable “Colloquies on the Simples & Drugs of India”, published in 1563. de Orta was a Portuguese, Sephardic Jewish physician, who worked for decades for the elite in the colony of Portuguese Goa, India.

He left numerous accounts of age-old Eastern farming practices. He records that:

The trees [of cinnamon] are about the size of olives or rather smaller, the branches are numerous and not crooked, but somewhat straight. The flowers are white, the fruit black and round, larger than a myrtle, or between that and a nut. The canela [cinnamon in Portuguese] is the second bark of the tree: for it has two barks like the cork tree, which has bark and shell…First, they take off the outer bark and clean the other. The outer bark, cut in squares, is then thrown on the ground. When on the ground it rolls itself up in a round form, so as to look like the bark of a stick which it is not. For the poles or sticks are the size of a man’s thigh. The thickest of the bark is the thickness of a finger. It takes a vermilion colour, or that which is given when burnt by the sun; or more like ashes mixed with red wine, very little of the cinder and a great deal of the wine…This year’s bark is taken and leaving the tree for three years it renews its bark.

(de Orta, 1563, pp. 129–130)

He tells us about the harvest of ginger in India:

It is gathered in December and January, dried and covered with clay in holes to prevent it from decaying. It is also enclosed in clay to make it weigh more and to keep it fresh, preserving its natural humidity. Besides, if it is not well covered with clay the worms eat it. It is also more humid and has a better taste.

(Ibid, p. 399)

Garcia de Orta described the nutmeg tree as follows:

It is like a pear tree, or, to be more exact, like a small peach tree. The rind is hard, the outer skin being harder than green pears. Removing the thick rind, there is a very fine rind like that which encircles our chestnuts. This goes round the nut. The nut is like a small gall nut. The delicate skin which encircles it is the mace…You must know that when the nutmeg begins to swell, it breaks the first rind, as our chestnuts burst their prickly covering, and the mace becomes very red, appearing like fine gram. It is the most beautiful sight in the world when the trees are loaded…

(Ibid, pp. 272–273)

He also provided the earliest record of black pepper cultivation. He wrote:

The tree of the pepper is planted at the foot of another tree, generally at the foot of a palm or cachou tree. It has a small root, and grows as its supporting tree grows, climbing round and embracing it. The leaves are not numerous, nor large, smaller than an orange leaf, green, and sharp pointed, burning a little almost like betel. It grows in bunches like grapes, and only differs in the pepper being smaller in the grains, and the bunches being smaller, and always green at the time that the pepper dries. The crop is in its perfection in the middle of January. In Malabar, the plant is of two kinds, one being the black pepper and the other white; and besides these there is another in Bengal called the long pepper…

(Ibid, p. 399)

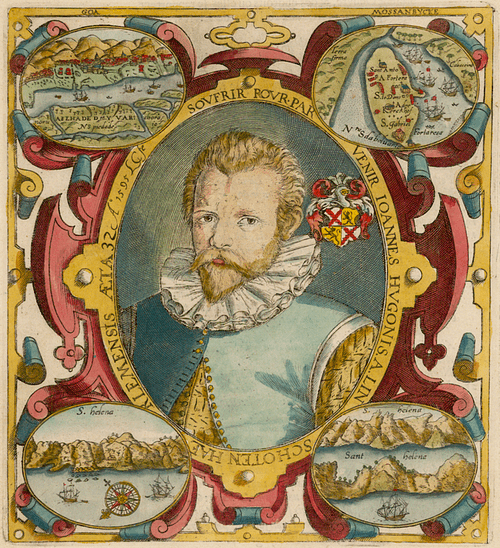

Jan Huygen van Linschoten

To a large extent, the Dutch path to the East Indies was paved by the adventurer Jan Huygen van Linschoten, who in 1595 published his Itinerario, almost an exposé of the Portuguese spice trade. Huygen was born in Haarlem, Holland in 1563, the son of an innkeeper. At the age of 16 he left for Spain to work with his brother in Seville for five years and then headed to Lisbon where he was employed as a merchant. In 1583 he landed a job as an accountant for the Archbishop of Goa, Joa͂o Vicente da Fonseca, and sailed off to India. Once there, Huygen devoted himself to learning about Goa and its inhabitants, assimilating a great deal of nautical and mercantile information by visiting the docks and talking to sailors. He obtained much first-hand knowledge of the ‘secret’ Portuguese trade routes and practices, and even befriended the Portuguese viceroy who let him see top-secret charts which he deviously copied. Huygen loved his life in Goa but was forced to leave in 1588 when his sponsor died. On the way home, his ship was wrecked near the Azores and he stayed for two years on the island of Terceira working to salvage and sell the spices that were aboard the ship. He also began writing his future publications.

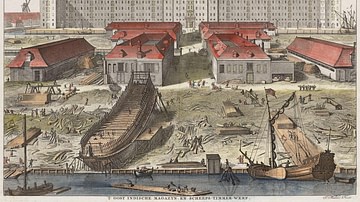

He finally got home in 1592 but his wanderlust was not extinguished, and he sailed to the Arctic with Willem Barents on the first two of his failed missions to find the Northeast Passage to China. It was not until 1595 that Huygen finally settled down and finished the Itinerario, describing his experiences in the East and offering detailed information on the route to India, the nature of the spice markets and the condition of the Portuguese Estado da Índia. The book clearly documented the growing European suspicion that the Estado da Índia had become decadent and overstretched. It showed that the Portuguese did not really have control of the markets in Java, which would ultimately become the centre of Dutch Indonesia. Most importantly, the book gave almost complete nautical and economic information about the Indian Ocean that until its publication had been a closely guarded secret of the Portuguese.

Ralph Fitch

In 1591, the first English worldwide traveler Ralph Fitch returned home after an astonishing eight-year journey to Mesopotamia, the Persian Gulf, the Indian Ocean, India and Southeast Asia. He returned with incredible first-hand knowledge of the inner workings of the spice trade and its opportunities. His journey began in February 1583 when he embarked for Aleppo, Syria with two merchants, John Newberry and John Eldred, a jeweler William Leedes, and a painter, James Story. Their trip was to generate trade and political alliances with the Ottoman Empire.

The five travelled down the Euphrates, crossed southern Mesopotamia to Baghdad, and then followed the Tigris to Basra where Eldred stayed behind to trade. Fitch and the others found passage down the Persian Gulf to the Portuguese fortress at Ormuz, where they were arrested as spies and sent across the Indian Ocean to Goa. There they were held captive until two English Jesuits helped them escape. Story chose to join their sect and remain, while the other two continued across India until they reached the court of the great Mogul leader Akbar at Agra.

Leedes got a post from Akbar and stayed put, while Fitch and Newberry continued on to Allahabad, after joining a huge convoy carrying salt, opium, lead and carpets. Newberry decided to head home at this point but was never heard from again. Fitch kept travelling, sailing down the Yamuna and Ganges Rivers from 1585 to 1586, and then across the sea to Pegu and Burma, where he further travelled deep into the interior of the continent on the Irrawaddy River. Early in 1588, he visited Malacca, and tried but failed to get passage into the South China Sea. At this point, he decided it was time to head towards home, travelling first to Bengal, round the Indian peninsula to Cochin and Goa, then on to Ormuz, up the Persian Gulf to Basra and then down the Tigris and Euphrates to Aleppo and Tripoli. Fitch arrived back in London on 29 April 1591, eight years after he had left, having visited the whole extent of the spice route spanning from the Levant to South East Asia. He appeared in London after being long presumed dead and until his real demise 20 years later, his eyewitness accounts served as a firebrand and blueprint for the early English missions to the Indian Ocean.

Legacy of the Four Great Travelers

The reports of these trailblazing four adventurers fired up the Dutch and English to follow the Portuguese to the riches of the Indian Ocean. As the 16th century ended, the Indian Ocean trade network was no longer a mystery to them, and they exuberantly entered into a power struggle with Portugal and each other for its control.