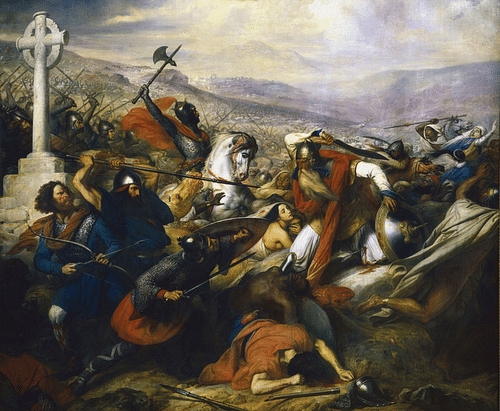

The Battle of Poitiers aka the Battle of Tours took place over roughly a week in early October of 732. The opposing sides consisted of a Frankish army led by Charles Martel (r. 718-741) against an invading Muslim army under the nominal sovereignty of the Umayyad Caliphate (c. 661-750) based in Damascus, Syria.

These two forces came together as Umayyad power sought expansion and plunder in European lands, while Frankish lords sought to defend and consolidate hold over their territory. Some have argued that this brief conflict influenced the fate of Christian civilization in Europe, while others see it as a simple border skirmish. The truth, it seems, lies somewhere in-between.

Though resulting in a Frankish victory, it was not simply Frankish power or the Battle of Tours alone which ultimately halted Umayyad expansion into Western Europe. Internal division within the Umayyad Caliphate itself, affecting its ability to wage war in the region was a major factor. In a broader context, Tours was not a determinant confrontation between the two sides, nor did it effectively deter or immediately diminish Umayyad strength in the region. Rather, the significance of Tours can be found in the circumstances occurring in the wake of Charles’s quick victory over Umayyad power.

Umayyad Expansion

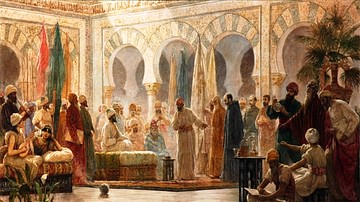

The Umayyad Caliphate was an evolving political and religious empire that grew out of Arabia in the 7th century, after the death of the Prophet Muhammed in 632. Between 632 and 709, Umayyad power expanded east into Persia, north into Byzantine lands, and west across North Africa, creating an enormous but politically unstable empire. One family, led by the governor of Syria, Muawiya (r. 639- 661 as governor; 661-680 as caliph) gained a dominant stake in the political and military control of this expansive force. Muawiya established his capital in Damascus around 661, where he consolidated his power and authority.

In just a few brief decades Umayyad power extended as far west as Morocco and into the Iberian peninsula, where they quickly conquered the existing Visigothic Kingdom. Populating their armies with North African tribesmen (Berbers) who had converted to Islam, they greatly disrupted the existing balance of power capturing the majority of cities south of the Pyrenees by 711. As early as 712, Umayyad armies led by Arab generals and manned by Berber tribesmen began raiding north of the Pyrenees into the borders of Frankish lands.

Frankish Power in Western Europe

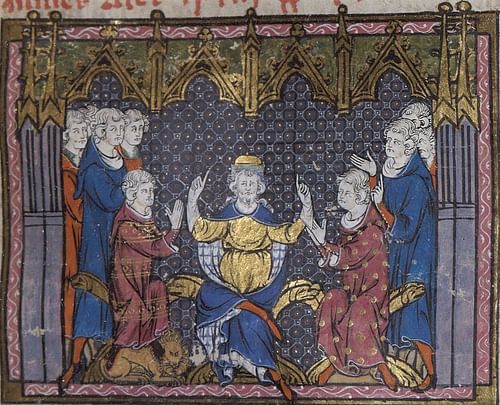

Early Frankish tribes came to power in the wake of the Roman Empire’s decline around the end of the 5th century. Renowned as great warriors, these Germanic tribesmen helped to fill the power vacuum left as Roman power receded across the province of Gaul (roughly corresponding to modern-day northern France, Belgium, and western Germany). As early as 481, a Frankish leader named Clovis united the disparate Frankish tribes, converted to Christianity, and established the Merovingian Dynasty, which would rule for roughly 250 years.

The Merovingian royal court was a violent one, with assassinations occurring so frequently it began to inhibit their ability to rule effectively. Such instability helped create an opportunity for an alternate position of power known as the major domus, or Mayor of the Palace, to slowly establish itself. Over time, it was through the mayors that the real power of Frankish authority was exercised.

When one of the more important early mayors, Pepin II (r. 687-714) died, a succession crisis ensued among his potential heirs. Ultimately, Pepin’s illegitimate son Charles (r. 714-741) emerged as the preeminent power. Charles spent most of his reign consolidating his power, fighting, and putting down rebellions, which arose upon Pepin II’s death. Charles fought eleven major campaigns from 715-731, gaining valuable experience, prestige, and allies that could be called upon when needed. However, it took time for Charles to consolidate control and some regions like Aquitaine in the south tried to claim independence. Aquitaine unintentionally played an important role as a buffer region between the Umayyads and Charles, while he worked to gain control over rebellious lords.

Umayyad-Frankish Conflict

Aquitaine was a semi-independent province in the early 8th century, nominally claimed by the Frankish kingdom, though ruled by a competent military commander, Eudes (669-735), who sought independence upon Pepin II’s death. Aquitaine bordered recently conquered Umayyad lands, so Eudes, not Charles, had the first contact with the Umayyads. Eudes did have some success, most notably against a major assault on the city of Toulouse in 719, where he was proclaimed as a hero of Christendom. Despite scattered victories, Umayyad armies continued raiding into Aquitaine over the years until, in 732, they smashed Aquitanian forces at Bordeaux, sacking the entire area.

Abd al-Rahman ibn Abd Allah al-Ghafiqi (d. 732) was the governor of Spain and commander of the raid into Frankish lands which defeated Eudes. Most raids prior to this campaign came from east of the Pyrenees because Arab forces controlled areas on the Mediterranean coast like Septimania, whose cities could be easily resupplied by sea. So, when Abd al-Rahman appeared over the western edge of the Pyrenees in 732, he surprised Eudes conquering Bayonne and Bordeaux in June 732. His army defeated, Eudes was forced to ride north seeking aid from Charles, though the two men were not fond of one another. Luckily for Charles and Eudes, the Umayyad army spent months plundering Bordeaux giving them time to assemble a force and march south to face this new threat.

The Battle of Tours

The Battle of Tours took place on 10 October 732 somewhere between Tours and Poitiers. The location of the battle is estimated to be near the conjunction of the Clain and Vienne rivers in a relatively open plain with surrounding woodlands. Abd al-Rahman’s army relied heavily on peoples of North African origin (Berbers), while Frankish forces also consisted of a mélange of nationalities likely speaking a range of languages. Both armies used infantry, though Umayyad forces relied more on mounted cavalry and were thought to hold a slight advantage through the use of the stirrup, which the Franks are not thought to have adopted yet. The Umayyad army was estimated at roughly 20,000-25,000 strong, while Frankish forces may have ranged from 15,000-20,000. Prior to the final battle a standoff between the two forces ensued for about a week, where smaller skirmishes were fought.

Surviving accounts of the battle are a little confused, though Frankish forces eventually came out victorious. One such account, Isidore of Beja’s Chronicle recalls the battle in the following passage:

For almost seven days the two armies watched one another waiting anxiously the moment for joining the struggle. Finally they made ready for combat. And in the shock of the battle the men of the North seemed like North [sic] a sea that cannot be moved. Firmly they stood, one close to another, forming as it were a bulwark of ice; and with great blows of their swords they hewed down the Arabs. Drawn up in a band around their chief, the people of the Austrasians carried all before them. Their tireless hands drove their swords down to the breasts [of the foe].

(Medieval Sourcebooks, Arabs, Franks, and the Battle of Tours)

Another passage by an anonymous Arab chronicler recounts the battle in the following way:

The Moslem horsemen dashed fierce and frequent forward against the battalions of the Franks, who resisted manfully, and many fell dead on either side, until the going down of the sun.

(Internet Medieval Sourcebooks Project, Anon Arab Chronicler: The Battle of Poitiers, 732)

Charles was aware of the Umayyads' reliance on cavalry and general offensive tactics, so he set his forces up in a phalanx to repel their charges. He was also using mainly local levies and militias who were more comfortable fighting on foot anyway, an ideal defensive tactic against cavalry charges. Fighting continued until a rumor spread through the Umayyad camp that their baggage train was being ransacked by the Franks, causing panic and a breakdown of discipline. The Arab commander Abd al-Rahman was killed trying to reestablish control over his troops, after which Umayyad resistance appears to have dissolved. An anonymous Arab Chronicler discusses these events in the following passage:

And while Abderrahman [sic] strove to check their tumult, and to lead them back to battle, the warriors of the Franks came around him, and he was pierced through with many spears, so that he died. Then all the host fled before the enemy, and many died in the flight…

(Medieval Sourcebooks, The Battle of Poitiers, 732)

Umayyad forces retreated during the night, leaving the Franks victorious. It was left to Eudes and his remaining troops to chase the Umayyads back across his lands and over the Pyrenees while Charles simply turned his forces around and marched back north. It was in Charles’ interest not to completely destroy the Umayyad raiders as they fled because they kept Eudes occupied in Aquitaine with his resources and attention focused south.

Debate over this battle questions the significance of Tours as an influential turning point in history. Charles’s victory in 732 did help to deter Umayyad settlement in Frankish territory, at least for that year. However, Tours was not necessarily the decisive conflict it is sometimes portrayed to be. For instance, Arab raids were launched in 734, 736, and their largest invasion occurred in 739 where they almost reached as far as Dijon before being beaten back by Frankish and Lombard forces. Certainly, these were not the actions of a defeated or even a demoralized force. Realistically, it seems that the only thing that really halted Umayyad raiding was internal political dissension within the Caliphate itself. J. F. C. Fuller discusses the influence of a Berber revolt in Morocco in the following passage:

About the time of the battle of Tours, internal dissensions broke out within the Arabian Empire, for though the Arabs were united by the bond of Islam they continued to maintain their tribal institutions and with them their old feuds and factions. Of the latter the two most important were the Maadites and the Yemenites…When the Maadites gained the upper hand, the Berbers of Africa refused to obey them, rose in revolt and most of what is now Morocco seceded…But the most important point to note is that, because of the revolt immediately after Abd-al-Rahman’s defeat at Tours, the Arab leaders in Spain were cut off from the Caliph in Damascus, and because of the revolution in Morocco they were no longer able to recruit their Berber armies. (347)

Without a steady supply of troops for their armies and easy plunder to entice men to join, Umayyad armies in Spain receded behind the Pyrenees, weakened and less able to continue raiding into Frankish lands. Therefore, the importance of Tours was not necessarily in the battle itself, as it had little impact over either sides’ ability to wage war against one another. The significance of Tours was mostly from the aura of prestige and military authority created around Charles as the savior of Christendom in the wake of his victory over the Muslim advance.

After Tours, Charles was recognized as the ultimate authority in the realm, which helped him centralize power around himself. One of the ways he did this was by paying his loyal followers with landed estates belonging to the Church. Recognized as the defender of Christendom from his victory at Tours, he was able to negotiate for and seize several estates owned by the medieval Church and distribute these lands to his loyal vassals. In this way, Charles helped to both reinforce the allegiance of his followers through gifts, while increasing his hold over lands in his kingdom by putting trusted military commanders in charge of them. According to McEvedy:

As the saviour [sic] of Christendom, he was able to force the Church to disgorge some of its vast holdings of land; these lands he gave to his retainers in return for their continuing service as knights. This contract, which transformed what had been a personal following into an instrument of use to his successors, proved to be the starting point for a new way of organizing the military. (34)

This form of payment through land distribution helped Charles centralize power around himself while enhancing his ability to raise troops for future conquests. For instance, when Eudes died just three years later in 735, Charles was in a much better position to march into Aquitaine and turn his heirs into vassals, ending any prospect of independence for the duchy.

Through his actions after Tours, Charles helped pave the way for his famous successor Charlemagne (r. 768-814) to rule over a relatively stable and powerful kingdom upon assuming the throne. Charles was so successful in his efforts that he established a new Frankish dynasty replacing the Merovingians with one centered around his family, known as the Carolingian Dynasty (c. 750-887). Arguably, the basis for these events can be traced partly back to the Battle of Tours in 732. Indeed, it was his victory at Tours that earned him the sobriquet 'Martel', or the 'hammer'.