Ashurbanipal's collection of Sumerian and Babylonian proverbs formed part of the famous Library of Ashurbanipal (7th century BCE) established at Nineveh for the express purpose of preserving the knowledge of the past for future generations. They are thought to have influenced the works included in the biblical Book of Proverbs, among other later wisdom texts.

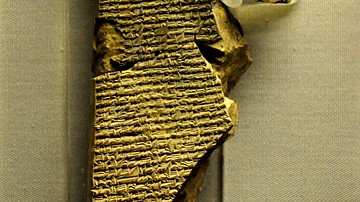

The works were written in Akkadian script and expressed common sense observations as well as insightful reflections. The oldest of the Sumerian proverbs would have been recorded from oral tradition in the Early Dynastic Period (2900-2334 BCE) in Sumerian, later preserved in Akkadian, while the Babylonian proverbs would date from the Old Babylonian Period (2000-1600 BCE) and later. So-called 'Babylonian proverbs' or 'Akkadian proverbs' are often Sumerian in origin, simply copied or reworded in later scripts.

Some of the proverbs of both sets are easily understood while others, relying on topical references now lost, make less sense to a modern reader. For example, "The en priest eats fish and eats leeks; but cress makes him ill" (5.6) was probably easily understood by an ancient Sumerian but has no resonance for a modern-day audience while "A house built by a righteous man is destroyed by a treacherous man" (23.4) remains relevant. Even so, the line about the en priest is still thought-provoking in that someone over 2,000 years ago felt that observation important enough to record it.

The works were first discovered by archaeologists Sir Austen Henry Layard and Hormuzd Rassam between 1850-1853 at Kouyunjik, Iraq in the ruins of the ancient city of Nineveh when they discovered the Library of Ashurbanipal. More proverbs were discovered during later excavations up through the 1930s. The precise location of specific tablets found at Nineveh is unclear as those from Ashurbanipal's library and the library of the North Palace were accidentally mixed together when they were brought to the British Museum, where they continue to be housed.

The proverbs were inscribed in cuneiform on clay tablets of various sizes and provide modern-day scholars with insight into the process of the Mesopotamian educational system as many clearly show an instructor's hand and a student's copy, while others represent homework assignments, and still others are highly polished and completed texts. In addition to the light the works shed on the education of scribes in ancient Mesopotamia, they also offer an introduction to the lives of the people in general regarding how they viewed the world, what they valued, and what they feared, all of which are familiar to anyone today.

Scribal Schools & Proverbs

The proverbs were clearly an important aspect of the educational system of the edubba ("House of Tablets"), the Sumerian scribal school established by the time of the Early Dynastic Period. The curriculum of the edubba continued, more or less unchanged, throughout the rest of Mesopotamia's history. Students were usually male (although there is evidence of female scribes), and all came from upper-class families who could afford to pay the tuition and had the luxury of sending their child to school for between 10-12 years instead of to work. Slaves were even educated by especially well-off masters who required literacy in conducting trade or by priests who needed literate accountants and secretaries for the temple.

As most of the proverbs were one-line statements, they were used as texts at the earliest stages of a student's education (which began as early as eight-years-old). Before a student could even attempt writing these sentences, however, they needed to master the basics of cuneiform script, which, after c. 3200 BCE, had 600 characters. A student also needed to learn how to form their own writing tablet out of clay and create their own writing implement, the stylus, from a sharpened reed. The student would then practice making the signs and characters, pressing the wedge-shaped tip of the stylus into moist clay, before they moved on to writing words and sentences.

Scholar A. Leo Oppenheim has outlined the progression of a student from their earliest attempts to completed works. This progress is clearly explained by Assyriologists Megan Lewis and Joshua Bowen of Digital Hammurabi:

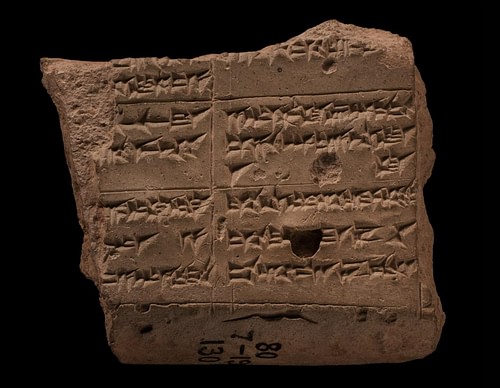

- Stage 1: 'Lentil-Shaped' tablets were used for the student to practice on making the proper wedges and signs and then lists of words.

- Stage 2: Somewhat larger tablets were used on which the instructor would write the text on the left side and the student would copy the same on the right. The right side of these tablets was often thinner than the left owing to the student erasing mistakes. The reverse of the tablet contained an older lesson the student had already mastered.

- Stage 3: Single-columned tablets were used and held a quarter or more of a long composition that had been completed and memorized.

- Stage 4: Large, multi-columned tablets held completed and polished compositions created from memory.

The Sumerian and Babylonian proverbs found at Ashurbanipal's library (as well as at other sites such as Sultantepe, Nippur, Uruk, etc.) demonstrate how they were used for all four of these stages. Scholar Jeremy Black explains how the proverbs were implemented in scribal training throughout Oppenheim's four stages:

Some of the tablets are small and round with only one two-or-three-line proverb written in good handwriting on the front (presumably by a teacher or advanced student) and again on the back rather more clumsily, presumably by a pupil who was learning it for the first time. Another, much larger standard tablet type typically bears 10-20 lines (5-10 proverbs) on the rectangular obverse, again in two copies: the model to be copied on the left, and the student's attempt to replicate it on the right. On the back of such tablets the student typically copied out a much longer extract from an earlier exercise or from an earlier part of the proverb collection. The third type of tablet is typically a rather smaller rectangle, bearing the student's copy alone of a similar-sized extract – 5-10 proverbs. Finally, there are large multi-columned tablets containing the whole of a collection, or significant fractions of it, which students appear to have written out on completing that stage of their education. (282)

Proverbs, therefore, served as the standard educational text from a scribe's first introduction to literacy through proficiency at graduation.

Proverbs in Daily Use

Once graduated, however, Mesopotamian scribes carried the proverbs with them, recorded others, created their own, and developed some of the concepts into longer didactic works, often in the form of fables. Scholar Samuel Noah Kramer comments:

The Sumerian men of letters included in their numerous proverb collections not only sayings of all kinds, such as maxims, truisms, adages, bywords, and paradoxes, but fables as well. These approach quite closely the classical "Aesopic" fable in that they consist of a short introductory passage in narrative form. (123)

Many proverbs feature oxen, donkeys and, especially, dogs personifying various aspects of life and clarified by the context of a line. Sometimes the dog is clearly a personification of 'hunger' or of 'laziness' or 'fate' – and sometimes the dog is just a dog, as in this proverb which is a simple observation on how dogs behave: "The smith's dog could not overturn the anvil; he therefore overturned the waterpot instead" (Kramer, 121).

Some proverbs seem paradoxical and their meaning obscure while others, such as "Friendship lasts a day; Kinship endures forever" are quite clear (Kramer, 121). Several proverbs are given in more than a single, pithy line as in this one relating what to treasure and what to guard against:

The desert canteen (oasis) is a man's life

The shoe is a man's eye

The wife is a man's future

The son is a man's refuge

The daughter is a man's salvation

The daughter-in-law is a man's devil.(Kramer, 121)

As Kramer notes, the ancient Mesopotamians used proverbs in the same way people do in the present day. The Sumerian proverb, "Upon escaping from the wild ox, the wild cow confronted me" is just an earlier version of the modern saying, "Out of the frying pan, into the fire" (122). These early proverbs of the Sumerians influenced the creation of later ones by the Babylonians and others and, eventually, the Hebrew scribes responsible for the best-known works from the biblical Book of Proverbs.

The Text

The following passages are taken from The Literature of Ancient Sumer, translated by Jeremy Black et al., and from The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature, translated by the same. The Babylonian proverbs come from Ancient History Sourcebook drawing on the original source of George A. Barton's Archaeology and The Bible, 1920. The below are only a sampling of a much larger collection and have been selected as a general representation of Mesopotamian proverbs.

Sumerian Proverbs

1.4. It became cloudy, but it did not rain. It rained, but no one undid their belt. Although the Tigris was on its high tide, no water reached the arable lands. It rained on the riverbank, but the dry land did not get any of it.

1.8. "Though I still have bread left over, I will eat your bread!" Will this endear a man to the household of his friend?

1.11. You don't speak of that which you have found. You speak only of what you have lost.

1.31. One does not return borrowed bread.

1.55. If you're poor, you're better dead than alive; if you've got bread, you can't afford salt; if you've got salt, you can't afford bread.

1.91. My girlfriend's heart is a heart made for me.

2.14. Fate is a dog walking always behind a man.

2.71. Tell a lie and then tell the truth; it will be heard as a lie.

2.81. One does not marry a three-year-old wife as a donkey does.

2.121. The good thing is to find it; the bad thing is to lose it.

5.6. The en priest eats fish and eats leeks; but cress makes him ill.

5.67. No one walks for a second time at the place where a lion has eaten a man.

5.78. A dog said to his master: "If my pleasure is of no importance to you, then my loss should not be either."

5.97. A dog which is played with turns into a puppy.

5.112. He is a dog without a tail.

7.8. The lord cursed Unug, but he himself was cursed by the lady of Inanna.

7.14. The sheepshearer is himself dressed in dirty rags.

7.31. He gathered everything for himself but had to slaughter his pig.

7.79. The sun never leaves my heart, which surpasses a garden.

7.81. A stranger's ox eats grass while one's own ox lies hungry.

7.104. Those who get excited should not become foremen. A shepherd should not become a farmer.

9.15. Nanni cherished his old age. He had not finished the building of Enlil's temple. He [had not finished] the building of the wall of Nippur. He had abandoned the building of the E-ana. He had captured Simurrum but had not managed to carry off its tribute. Mighty kingship was not bestowed upon him. Was not Nanni thus brought to the Underworld with a depressed heart?

14.1. Let the favor be repaid to him who repays a favor.

14.19. Both the palace and the netherworld require obedience from their inhabitants.

21.2. Into a plague-stricken city one has to be driven like a pack-ass.

23.4. A house built by a righteous man is destroyed by a treacherous man.

25.6. The palace is a slippery place, where one slips. Watch your step when you decide to go home.

27.1. The palace bows down, but only of its own accord.

28.1. The palace – one day a lamenting mother, the next day a mother giving birth.

29. Even the palace cannot avoid the wasteland. Even a barge cannot avoid straw. Even a nobleman cannot avoid corvee work.

31.4. What flows in is never enough to fill it, and what flows out can never be stopped – don't envy the king's property!

31.6. When a man sailing downstream encounters a man whose boat is traveling upstream, an inspection is an abomination [to the gods].

Babylonian Proverbs

1. A hostile act you shall not perform, that fear of vengeance shall not consume you.

2. You shall not do evil, that life eternal you may obtain.

3. Does a woman conceive when a virgin, or grow great without eating?

4. If I put anything down it is snatched away; if I do more than is expected, who will repay me?

5. He has dug a well where no water is, he has raised a husk without kernel.

6. Does a marsh receive the price of its reeds, or fields the price of their vegetation?

7. The strong live by their own wages; the weak by the wages of their children.

8. He is altogether good, but he is clothed with darkness.

9. The face of a toiling ox you shall not strike with a goad.

10. My knees go, my feet are unwearied; but a fool has cut into my course.

11. His ass I am; I am harnessed to a mule – a wagon I draw, to seek reeds and fodder I go forth.

12. The life of day before yesterday has departed today.

13. If the husk is not right, the kernel is not right, it will not produce seed.

14. The tall grain thrives, but what do we understand of it? The meager grain thrives, but what do we understand of it?

15. The city whose weapons are not strong the enemy before its gates shall not be thrust through.

16. If you go and take the field of an enemy, the enemy will come and take your field.

17. Upon a glad heart oil is poured out of which no one knows.

18. Friendship is for the day of trouble, posterity for the future.

19. An ass in another city becomes its head.

20. Writing is the mother of eloquence and the father of artists.

21. Be gentle to your enemy as to an old oven.

22. The gift of the king is the nobility of the exalted; the gift of the king is the favor of governors.

23. Friendship in days of prosperity is servitude forever.

24. There is strife where servants are, slander where anointers anoint.

25. When you see the gain of the fear of god, exalt god and bless the king.

Conclusion

As with the other texts discovered in the ruins of Ashurbanipal's library in the 19th century, the Sumerian and Babylonian proverbs changed people's understanding of their history and their previous interpretation of the Bible. The discovery of The Epic of Gilgamesh, which contained a story of the Great Flood, and the Myth of Adapa, on the fall of man, both predating the biblical narratives by thousands of years, meant the Bible could no longer be claimed to be an original work nor, as had been believed, the oldest book in the world.

The biblical proverbs were now understood as having developed from these earlier works but, if anything, this only increased their relevance and humanity. As Kramer comments:

One of the significant characteristics of proverbs in general is the universal relevance of their content. If you ever begin to doubt the brotherhood of man and the common humanity of all peoples and races, turn to their sayings and maxims, their precepts and adages. More than any other literary products, they pierce the crust of cultural contrasts and environmental differences, and lay bare the fundamental nature of all men, no matter where and when they live. (117)

The discovery of the Sumerian and Babylonian proverbs of Ashurbanipal's collection, and those found elsewhere, connected the people of the modern era with those of the ancient past on the most basic and profound level in expressing the same familiar concerns, hopes, humor, relationships, fears, and joys. The ancient proverbs continue to provide that same kind of connection with an immediacy not experienced in longer works, making them the best of emissaries between the past and the present.