Women in the New Testament are presented for the most part along the contours of both Jewish and Greco-Roman concepts of the social construction of gender roles. Women’s value to society was in their role in procreation. There are some exceptions, however, in the gospels and particularly in the letters of Paul.

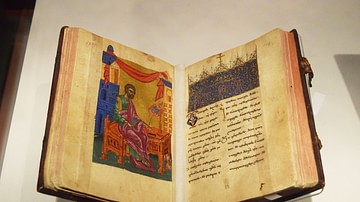

The four gospels (Mark, Matthew, Luke, and John) were written 40-70 years after the death of Jesus. Thus, we only know about Jesus’ views on women from their reports, filtered through their own cultural and religious ideas. Like the stories of women in the Old Testament, the gospel writers utilized women to critique a loss of faith or lack of insight in relation to men.

Jesus & Women in the Gospels

Beginning in the last century, with the rise of feminism and feminist theology, it became popular to label Jesus a feminist. Feminism is a modern construct, but the label is applied to what is deemed the deliberate inclusion of women in his ministry. Given the social/cultural position of women in the ancient world, this claim is often made that Jesus liberated women from oppressive Judaism as well as Greco-Roman culture.

There is no preaching on the status of women in any of the gospels, but there are several stories of Jesus’s encounters with women. Particularly in Matthew, Jesus was always being accused of eating (sharing his couch) with "tax collectors and sinners" (and it is always phrased in that combination, e.g. Matthew 9:10). However, the accusations always stem from the polemic of Jesus’ opponents. By tradition, the "sinners" are assumed to be prostitutes. In the gospels, many of the women are presented juxtaposed to the men; they have more understanding of who Jesus is. Matthew’s Jesus claimed that prostitutes will enter heaven before the Pharisees.

Luke related the story of such a prostitute washing the feet of Jesus while he had dinner at the home of a Pharisee. She applied perfume and wiped his feet with her tears (Luke 7:36-49). The interpretation was that she performed this act as part of the anticipated funeral rituals for Jesus’ upcoming death. The passage includes a parable on forgiveness, even to the lowly.

The named disciples in the gospels are all men, symbolizing the restoration of the twelve tribes, but several women are mentioned as both traveling with the group as well as supporters of Jesus' ministry:

The Twelve were with him and also some women who had been cured of evil spirits and diseases: Mary (called Magdalene) from whom seven demons had come out; Joanna the wife of Chuza, the manager of Herod's household; Susanna; and many others. These women were helping to support them out of their own means. (Luke 8:1-3)

"Out of their own means" indicates that these women were from the higher classes who had access to their husbands’ funds or income from estates.

In general terms, Jesus appeared to support marriage with a reference to Genesis:

"But at the beginning of creation God 'made them male and female.' 'For this reason a man will leave his father and mother and be united to his wife, and the two will become one flesh.' So they are no longer two, but one flesh. Therefore what God has joined together, let no one separate." (Mark 10:6-9)

"Anyone who divorces his wife and marries another woman commits adultery against her. And if she divorces her husband and marries another man, she commits adultery" (Mark 10:11-12). The gospels also show Jesus welcoming children which can be interpreted as condoning marriage.

Jairus was a synagogue leader and apparently a follower. Friends had sent for Jesus because his daughter was ill, but she died before he could get there. Jesus informed the grievers that she was simply asleep. He then went to her and said: "Talitha kum" which means "little girl, get up" in Aramaic (Mark 5:41). Luke included the raising of a widow of Nain’s dead son in the middle of the funeral. We know nothing about the ethnic identity of this woman, but Luke modeled much of the ministry on the Prophets Elijah and Elisha. Both Prophets spent time with Canaanite widows, restoring their sons to life.

When Jesus traveled to Tyre (Phoenicia), a local woman begged Jesus to cure her daughter who was possessed by a demon.

"First let the children eat all they want," he told her, "for it is not right to take the children’s bread and toss it to the dogs." "Lord," she replied, "even the dogs under the table eat the children’s crumbs." Then he told her, "For such a reply, you may go; the demon has left your daughter." (Mark 7:27-29).

This story is important in the fact that Gentiles (non-Jews) were beginning to outnumber Jewish followers. It serves the rhetorical purpose that Jesus himself approved of the mission to the Gentiles.

The most popular story in which to analyze the liberation of women in the gospels is found in the story of the hemorrhaging woman. A woman who had been "bleeding for twelve years" touched Jesus’ garment and was healed (Mark 5:24-34). Women were ritually impure for seven days of their menstrual cycle; childbirth involved purity separation for thirty days. Such purity rules related to one’s presence in the Temple which was a sacred space. Impurity was resolved with the separation of mundane life, and the passage of time. This story was used polemically to assert that Judaism oppressed women. However, all ancient cultures had ritual purity restrictions.

Marys in the Gospels

There are several women named Mary in the gospels. This is because it was the Greek (Maria) for Miriam, the sister of Moses and a popular role model: Mary, mother of Jesus; Mary Magdalene; Mary, mother of James and Joses, (Mary) Salome (who is also identified as the mother of the sons of Zebedee); Mary of Clopas; Mary of Bethany, sister of Martha and Lazarus. Without detail, some of these women are identified depending upon context and placement in the narratives.

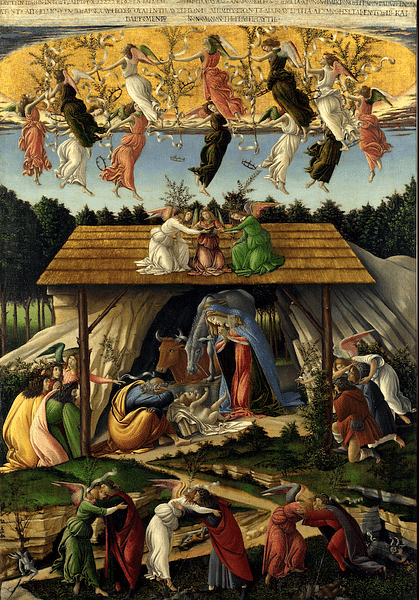

Mary, the Mother of Jesus

The earliest mention of Mary as Jesus' mother is in Mark’s gospel (c. 70 CE), but it is in Matthew (c. 85 CE) and Luke (95 CE) that we have the role of Mary in the nativity of Jesus. Both utilized the concept that the spirit of God came upon Mary as a virgin, and both claimed that this fulfilled what the Prophets had predicted. Luke included an annunciation to Mary from the angel Gabriel. Annunciation stories in the book of Genesis were used to relate divine intervention in the birth stories of women.

Luke’s nativity began with the birth of John the Baptist. Using the typology of barren women, Luke reported that Elizabeth and Zechariah were old and barren. An angel appeared to Zechariah when he was serving in the Temple and told him that Elizabeth would bear a son, John. Luke then related the visit of her cousin, Mary, when the fetus in Elizabeth’s womb "leaped for joy" (Luke 1:44), at the coming of the mother of his lord. Only Luke cited this familial relationship. John’s gospel has the mother of Jesus instrumental in the first of the miracle stories in that gospel. At the wedding at Cana, she directed Jesus to miraculously turn the vats of water into wine.

Mary & Martha

Both Luke and John contain stories of two sisters, Mary and Martha. In Luke, they appear to live independently:

As Jesus and his disciples were on their way, he came to a village where a woman named Martha opened her home to him. She had a sister called Mary, who sat at the Lord’s feet listening to what he said. But Martha was distracted by all the preparations that had to be made. She came to him and asked, "Lord, don’t you care that my sister has left me to do the work by myself? Tell her to help me!" "Martha, Martha," the Lord answered, "you are worried and upset about many things, but few things are needed—or indeed only one. Mary has chosen what is better, and it will not be taken away from her." (10:38-42)

John appears to have known this story but adds the detail that they were sisters of Lazarus whom Jesus had raised from the dead:

Here a dinner was given in Jesus’ honor. Martha served, while Lazarus was among those reclining at the table with him. Then Mary took about a pint of pure nard, an expensive perfume; she poured it on Jesus’ feet and wiped his feet with her hair. ... But one of his disciples, Judas Iscariot, who was later to betray him, objected ... "Leave her alone," Jesus replied. "It was intended that she should save this perfume for the day of my burial. You will always have the poor among you, but you will not always have me." (John 12:2-7).

Mary Magdalene

When the disciples abandoned Jesus after his arrest and fled, the gospels relate that the women remained loyal, looking on from a distance. The lists do not agree but contain all these women:

- Mary Magdalene

- Mary the mother of James and Joseph, the mother of the sons of Zebedee,

- Mary the mother of James the younger and of Joses

- Salome

John has "his mother, and his mother’s sister, Mary the wife of Clopas, and Mary Magdalene" (19:25). The women went to the tomb Sunday morning to finish the funeral rituals (the Sabbath had intervened). Again, the lists do not match: "Mary Magdalene and Mary the mother of James, and Salome" (Mark 16:1); "Mary Magdalene and the other Mary" (Matthew 28:1), "Mary Magdalene, Joanna, Mary the mother of James, and other women" (Luke 24:10). John singularly has Mary Magdalene who received a post-resurrection appearance by Jesus (20:11-18).

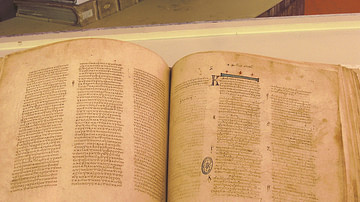

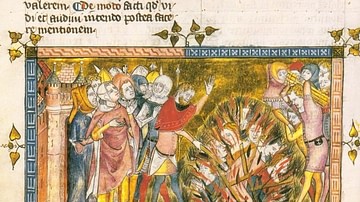

In the various lists of women in Jesus’ circle, Mary Magdalene is consistently included in all four gospels. Despite 1400 hundred years of tradition, and the constant portrayals by Hollywood, Mary Magdalene was never described as a prostitute in the gospels. She was not directly named a disciple, although the Greek for "follower" could imply a similar meaning. It was Pope Gregory I (540-604), who associated Mary Magdalene with two stories from the gospels: the sinful woman who anointed Jesus, and the story of the woman caught in adultery. Only found in later manuscripts of Luke and John, there is a story of a woman who was going to be stoned to death for adultery (not prostitution, as prostitution in the ancient Mediterranean was not a crime). Jesus rescued her from the mob. In both manuscripts, the woman is not named, and the Eastern Orthodox Churches do not accept this identification of Mary Magdalene.

Women in the Pauline Communities

The details of the roles and status of women in the earliest communities are found in the letters of Paul the Apostle (50s-60s CE) and the Deutero-Pauline letters. Paul named several women, both Jewish and Gentile, and often included details of their contributions to the community. Paul claimed that some of the apostles traveled with their wives. Many of the names are Greek, but we cannot determine their origin; many Jews in the cities of the Roman Empire also had Greek names.

Women traveled with their husbands or brothers and often worked in pairs: Prisca, Junia, Julia, Nereus’ sister, Mary (Romans 16). He referred to Junia as an apostle, although we are not sure if this designation set her apart from others. Junia was also “imprisoned for her labor,” but we do not know the details.

Christians met in houses, not church buildings, and it appears that many of the named women in Paul’s letters had large enough houses in which to hold their meetings. Being the head of a household was the most likely way in which women were given opportunities for leadership. He praised Phoebe for her hospitality, in the community at Cenchreae (near Corinth). Paul provided her with three titles: diakonos (deacon), sister, and prostatis (a female patron or benefactor). He praised Chloe and her people, which indicates that Chloe managed a household (1 Corinthians 1:11).

Paul believed that Christ would return soon, and then the entire cosmos would be transformed. This meant that all social conventions would be upended: "There is neither Jew nor Gentile, neither slave nor free, nor is there male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus" (Galatians 3:28). Teaching his communities to live as if the kingdom of God was already here is most likely the reason for the elevation of women in Paul’s communities.

Women in the Acts of the Apostles

The Acts of the Apostles (written by Luke), narrates the stories of how Christianity was introduced by missionaries in the cities of the Roman Empire. The named women reflect the contributions of women in the movement.

Luke reported that after Jesus ascended, his followers met in an upper room where "They all joined together constantly in prayer, along with the women and Mary the mother of Jesus, and with his brothers" (Acs 1:14). This mention indicates that Mary had some standing in the community after Jesus died.

Another woman mentioned by name is Tabitha Dorcas who apparently ran her own business, making tunics especially for the poor:

In Joppa there was a disciple named Tabitha (in Greek her name is Dorcas); she was always doing good and helping the poor. About that time, she became sick and died, and her body was washed and placed in an upstairs room. (Acts 9:36-37)

The believers sent for Peter who was nearby, who came and raised her from the dead.

Another passage mentions Lydia when Paul was in Philippi:

On the Sabbath we went outside the city gate to the river ... We sat down and began to speak to the women who had gathered there. One of those listening was a woman from the city of Thyatira named Lydia, a dealer in purple cloth. She was a worshiper of God. The Lord opened her heart to respond to Paul’s message. When she and the members of her household were baptized, she invited us to her home. "If you consider me a believer in the Lord," she said, "come and stay at my house." And she persuaded us. (Acts 16:13-15)

After this, Paul left Athens and went to Corinth. There he met a Jew named Aquila, a native of Pontus, who had recently come from Italy with his wife Priscilla, because Claudius had ordered all Jews to leave Rome. Paul went to see them, and because he was a tentmaker as they were, he stayed and worked with them. (Acts 18:1-3)

The story of Priscilla and Acquila is one those rare gems in New Testament scholarship where we have characters or events that are found outside the gospels. Paul mentioned them in 1 Corinthians. The expulsion of the Jews from Rome is found in the Roman historian Suetonius’ (69-122 CE) Lives of the Caesars.

The Changing Roles of Women: The Pastorals

1 and 2 Timothy, and Titus in the New Testament, are collectively known as the Pastorals. They contain information that was important for pastors or leaders of Christian communities. Written in Paul’s name, these letters date from 80 CE to the end of the 1st century CE.

In the early teaching that social conventions would be upended, Paul urged widows in Corinth not to remarry, for the kingdom was coming soon. Greco-Roman society had traditionally pressured widows to remarry. Offering a way out of this social responsibility, women may have flocked to these new communities. And they most likely lived in the bishop’s house, which was apparently causing a scandal.

Timothy applied rules for widows. Widows who have children must be supported by them and their families. No widow under the age of 60 would be taken in. The letter reports that younger widows only care about their dress and sit around and gossip all day. "So I counsel younger widows to marry, to have children, to manage their homes and to give the enemy no opportunity for slander." (1 Timothy 1 5:14) At the same time, the status of Christian women became diminished:

I do not permit a woman to teach or to assume authority over a man; she must be quiet. For Adam was formed first, then Eve. And Adam was not the one deceived; it was the woman who was deceived and became a sinner. But women will be saved through childbearing—if they continue in faith, love and holiness with propriety. (1 Timothy 2:12-15)