The stories that make up what is known today as Norse mythology once informed the religious beliefs of the people of regions including Scandinavia and Iceland. To the Norse, the world was an enchanted place of gods, spirits, and other entities that needed to be honored to maintain personal and communal balance.

The Norse deities arrived in Scandinavia with Germanic migrations c. 2300 - c. 1200 BCE and were transmitted orally by poets (known as skalds) presumably from about that time until the rise of Christianity in the region c. 1000 CE when they began to be committed to writing. The world of Norse mythology encompasses the time from the beginning of the world until its end in the flames of Ragnarök which would lead to the birth of a new world that maintained the order established by the old gods at the beginning of time. It is possible, however, that in the original vision, there was no rebirth, only the end of all things, encouraging adherents to appreciate the time they had in a world which, like themselves, was doomed from its inception.

This understanding could have developed, however, even if the concept of rebirth was part of the pre-Christian story of Ragnarök in that, whatever new world came next, it was not the one the people had known. Those living in the Viking Age (c. 790 - c. 1100) recognized they were already in the "end times" as the first herald of Ragnarök – the death of the god Baldr – had already happened and the world was progressing daily toward its end.

To navigate this world, one relied on the entities of the invisible realms surrounding that of mortals, primarily the gods of Asgard (the Aesir), who had established order in the beginning and maintained it against the threat of chaos. One needed to also be aware of other beings, however, such as elves, dwarves, and other elemental spirits one did not wish to offend and who were much preferred as allies than antagonists.

The Norse belief system was as integral a part of the people’s lives as that of any other culture of antiquity or religious belief in the present day. It was the last pagan system to fall to Christianity but was so potent a force among the people that it was preserved in the works of Christian scribes. In the present, it remains one of the most popular and influential mythological systems, inspiring films, television shows, and popular literary works such as The Lord of the Rings and Game of Thrones to name only two.

Its influence has gained further ground through the modern faith of Asatru ("faith in the Aesir"), which has revived the old religion and raised a temple to the Norse gods in Iceland. Even so, there are many aspects of the mythology often overlooked or misunderstood, of which ten follow below.

Norse Mythology Written by Christians

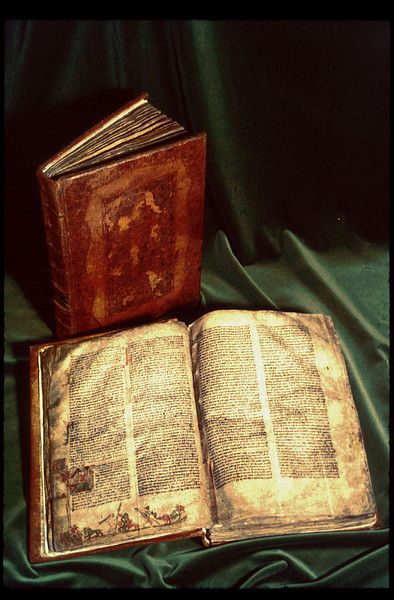

Although the pre-Christian Norse had the writing system of the runic alphabet, runes were used for brief messages such as inscriptions on memorials, not for longer works. As noted, the great tales of the gods and heroes were transmitted orally until the arrival of Christianity which, because it was based on the revelation of scripture, encouraged literacy. Christian scribes preserved the tales either to argue against their validity or, it seems, as historical curiosities or for reasons that are unclear. The two main sources for all extant Norse mythology are the Poetic Edda and the Prose Edda, both from the 13th century. The Poetic Edda is a compilation of verses from around the 10th century while the Prose Edda is a narrative written by the Icelandic mythographer and scholar Snorri Sturluson (l. 1179-1241) around 1220. A number of modern-day scholars have attempted to reconstruct pre-Christian Norse beliefs using textual and archaeological evidence, but any conclusions must finally be speculative because there is no written record of the tales before the arrival of the Christian missionaries.

Days of the Week Named after Norse Gods

The popularity of the deities of the Norse pantheon is evident in the names of the days of the week in English, influenced by Germanic and Scandinavian languages brought to Britain before and during the Viking Age. These languages, in turn, were influenced by Latin, brought to various regions by the armies of the Roman Empire. The seven-day week was adopted by the Roman emperor Constantine the Great in 321 CE, replacing the 8-day week the Romans had inherited from the Etruscans. The seven days were all named in honor of a Roman deity, still evident in the days’ names in Romance languages, but in English took on Norse names.

- Sunday – honoring Sunna, Norse goddess of the sun

- Monday – in honor of Mani, Norse god of the moon and brother to Sunna

- Tuesday – named after Tyr, god of war, whose sacrifice helped bind Fenrir

- Wednesday – honoring Odin (also given as Woden) king of the gods

- Thursday – Thor’s Day, in honor of the god of thunder and the sky

- Friday – in honor of Frigg or Freyja who may have once been a single goddess

- Saturday – honoring the Roman god Saturn among whose attribute was renewal, and the seventh day of the week was laundry day for the Norse, so they kept the Roman name

Gods & Giants are Related

Although the giants of the realm Jotunheim became the enemies of the gods of Asgard, they were the original entities who gave birth to the gods. The first creature to emerge in the Nine Realms of Norse cosmology was the giant Ymir followed by the cow Audhumla. Audhumla uncovered the god Búri by licking the ice, and Búri mated with the giantess Bestla, who gave birth to the gods Odin, Vili, and Vé, while Ymir gave birth to the giants through self-fertilization. Odin and his brothers killed Ymir and the other giants, but two, Bergelmir and his wife, escaped and produced the other giants who would afterwards become the sworn enemies of the gods. The relationship between the gods and giants is epitomized in the figure of Loki, the trickster god, whose father was a jötunn (someone from Jotunheim) and mother a goddess. A jötunn was not necessarily a giant – both Loki and his daughter Hel (also a jötunn) are depicted as normal-sized beings – but the jötnar (plural of jötunn) seem to have a familial relationship with the giants, and both are associated with Jotunheim. The concept of the giants as unrelated to the gods, therefore, is incorrect as is the claim that every jötunn was a giant.

First Humans Made from Trees

According to the poem Völuspá from the Poetic Edda, the first humans were the male Ask and the female Embla who were found by the gods Odin, Hœnir, and Lodurr on a nameless shore and given life. Odin gave them spirit in the form of breath, Hœnir gave them intelligence and a voice, and Lodurr provided blood to warm their bodies and give them good coloring. Sturluson adapted this story in the Prose Edda where the gods find two trees (usually given as an Ash tree and Elm tree) and create the first humans from these. The identification of Embla with an Elm tree has been challenged (she possibly came from a vine) but is usually accepted. These first two humans are mirrored by the couple Lif and Lifthrasir who appear after Ragnarök to repopulate the world.

Loki is Not Thor’s Brother

Although the Marvel Cinematic Universe has popularized Loki as Thor’s brother, the two are not related in Norse mythology. Loki, a jötunn, is Odin’s blood brother though how that relationship was forged is unknown. In the poem Lokasenna ("Loki’s Taunts") where he insults a number of the Asgardians at a banquet, he references his relationship with Odin without elaborating upon it. An original audience is assumed to have known the story of how Odin and Loki formed their bond, but this was either never committed to writing or was lost. Thor would be more of an honorary nephew to Loki than anything else – if that – and in the Lokasenna, he is the only god Loki seems to respect and fear.

Thor’s Hammer due to Loki’s Antics

At the same time, Loki is not above causing whatever trouble he may have in mind for Thor. In one story, when Thor’s hammer is stolen, Loki proposes the plan for Thor to dress as Freyja to fool the giant who stole it into letting his guard down so they can get it back. Although the plan works, it still humiliates Thor who must dress as a woman. The very existence of Thor’s famous hammer is also due to Loki who decides one morning to cut the hair of Thor’s wife, Sif, while she is sleeping. He knows this will enrage Thor but does it anyway. Thor threatens his life, and Loki promises to replace her hair by going to the dwarves and asking them to make her a new golden head of hair. Since Loki cannot resist causing trouble, he challenges the dwarves to a contest to make even grander objects than they already have while, in the form of a gadfly, tormenting them so they make mistakes. One of the magical objects created is Mjölnir, the hammer of Thor, whose handle is shorter than a regular hammer because of Loki’s antics.

Gods Are Not Immortal

Unlike the deities of the pantheons of other cultures, the Norse gods are not immortal; they are only unusually long-lived and owe their youth and vitality to the goddess Idunn and her magical apples. It is thought that, originally, it was Idunn herself who enabled the gods to remain young and healthy, but by the 13th century, the apple motif had been introduced and was developed by Sturluson in the Prose Edda. In the section Skáldskaparmál, Loki is abducted by a giant in the form of an eagle who will only release him if he promises to lure Idunn and her magical apples beyond the walls of Asgard. Loki does so, and Idunn is taken by the giant. The gods begin to grow old and grey, and Loki must then fly to the giant’s realm and bring the goddess and her apples back to Asgard. The best-known depiction of the gods as mortal, however, comes from the tale of Ragnarök in which many die in a great battle.

Ship Naglfar Made from Fingernails of the Dead

Ragnarök is the end of the world when the gods and the heroes of Valhalla fight against the forces of chaos, and the Nine Realms are destroyed by fire and flood. A little-known detail of the final battle concerns the ship Naglfar which will carry the army of the dead, provided by Hel, to the battlefield to face the gods. Naglfar is made entirely from the unclipped fingernails (and possibly toenails) of the dead. The ship will not be able to sail until it is completed and can only be completed by harvesting the nails of the dead. This aspect of the story encouraged careful personal hygiene – which the Vikings were famous for, contrary to their popular depiction as dirty or unkempt – in that one would keep one’s nails short and well-cared for to stave off the completion of Naglfar and so the arrival of the end of days.

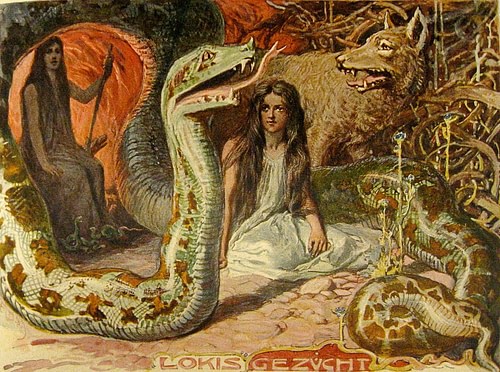

Loki’s Children Launch Ragnarök

Although Loki aligns himself with the gods of Asgard and often proves himself helpful, he and his children are the central antagonists of the gods at Ragnarök. Loki mates with the giantess Angrboda ("she who offers sorrow"), who gives birth to the wolf Fenrir, the serpent Jörmungandr, and the jötunn Hel, keeping all three with her in Jotunheim. Odin hears of Loki’s children through a prophecy that they will one day cause the gods great trouble and has them taken from their mother. He throws Jörmungandr into the sea, sends Hel to the dark realm below the earth as Queen of the Dead, and has Fenrir bound to a rock on an island. Loki is also finally imprisoned after he engineers the death of Baldr and insults the gods at their feast. At Ragnarök, Loki and these three – as well as two of his other children, the wolves Sköll and Hati, lead or supply the forces of chaos who battle the gods resulting in the deaths of Odin, Thor, Tyr, Heimdall, and others.

Rebirth after Ragnarök May Have Been Christian Construct

Many of the best-known gods die at Ragnarök, and the Nine Realms fall as the fire giant Surtr sets the world on fire with his flaming sword, but, afterwards, life begins again in a new cycle. The surviving deities, including Frigg, Freyja, Sif, Idunn, Thor’s sons, and Odin’s sons, return to the place where Asgard once stood and tell the tales of Odin and the great battle to a new generation of gods. Two humans, Lif and Lifthrasir, who hid themselves during Ragnarök, come out and repopulate the world and life goes on. The description of this new world where fields "bear harvest without labor" and there is no sickness resonates, for some scholars, with Christian imagery and evokes the Garden of Eden suggesting that this was a later addition to a much older vision. Scholar Daniel McCoy, for example, notes that this kind of rebirth is inconsistent with pre-Christian Norse belief, but, as noted, since the myths were all recorded in the Christian era, it is difficult to tell what form they might have taken prior to the arrival of Christianity. Grave goods excavated from tombs and ship burials strongly suggest a belief in an afterlife, and it is clear there were pre-Christian realms of the dead awaiting the souls of the deceased so the rebirth motif of the Ragnarök tale may be much older than scholars like McCoy have claimed.

Conclusion

Adherents of the old faith did not worship their gods in temples (although temples to the gods were raised, notably the famous Temple at Uppsala, Sweden, described by Adam of Bremen in the 11th century) but at outdoor shrines and sacred sites where the power of the invisible realms was most potent. They had no name for their religion but referred to it as sidr ("custom" or "tradition"), which came to be interpreted to mean "the old ways" once Christianity had supplanted it and was known as "the new way". Norse beliefs continued to influence the culture and practices of Scandinavia and Iceland – as well as other regions – long after Christianity had become dominant, however, and continue to do so today.

The neo-pagan religion of Asatru has revived Norse religious belief and practices and, in Iceland and Denmark, is the fastest-growing religion. The faith claims to represent "the old ways" as closely as possible and emphasizes respect for the earth and invisible entities as well as one’s ancestors and traditions. One of the harbingers of Ragnarök was drastic climate change followed by a breakdown of traditional customs and relationships, and Asatru has called attention to these same problems in the modern age resulting from too great a focus on individual profit and comfort at the expense of the communal – global – good. Asatru seeks to create the kind of balance encouraged by Norse mythology by removing it from the realm of "myth" and returning it to an active faith in which gods, spirits, and humans work together in harmony to maintain order and celebrate the earth and all its inhabitants, both seen and unseen.