The first plantations in the Americas of sugar cane, cocoa, tobacco, and cotton were maintained and harvested by African slaves controlled by European masters. When African slavery was largely abolished in the mid-1800s, the center of plantation agriculture moved from the Americas to the Indo-Pacific region where the indigenous people and indentured servants were forced to grow sugarcane, tea, coffee, and rubber.

In the late 1800s, a new round of plantations reemerged in Central America where mostly Mayan bonded servants harvested banana and coffee. In the current century, plantation agriculture has been focused on Laos and Myanmar and the large islands of Sumatra, Borneo, and New Guinea. The labor force has been largely forced local labor.

Atlantic (1432-1850)

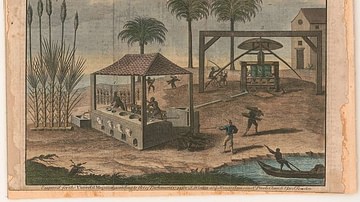

The first sugar cane plantations were planted in 1432 after the Portuguese colonization of Madeira on the Atlantic coast of North Africa. The Portuguese discovered Brazil in 1500, and it did not take them long to begin establishing sugar cane there. The first sugar was produced in 1518, and by the late 1500s, Portuguese Brazil had become the leading supplier of sugar to the European markets.

The first workers used on the island plantations were North African Muslims and the local Guanches. When too few of the Guanches were left alive from disease and overwork, African slaves were imported. In Brazil, the Portuguese began by subjugating the local Tupi to work in their mines and harvest their fields; however, the Tupi proved to be poorly adapted to the routine, sedentary lifestyle of farming and were particularly uncooperative slaves. They were very subject to western diseases and found it relatively easy to run away and hide in the dense forest. The Portuguese solution to this problem was to turn to African slavery. By the mid-16th century, African slavery predominated on the sugar plantations of Brazil, although the enslavement of the indigenous people continued well into the 17th century.

Ultimately, the Brazilian sugar industry found stiff competition from the Caribbean, first from the tiny island of Barbados, and then a hodgepodge of British-, French-, and Dutch-controlled islands including British Antigua and Nevis, French Martinique, Guadeloupe and St. Dominique (now Haiti), and French- and British-controlled sections of St. Kitts. British Jamaica would become the crown jewel of Caribbean sugar production, after a long and difficult settlement period. The first Europeans in Jamaica were the Spanish in 1510, but it did not become a major sugar producer until the British invaded in 1655.

As sugar production spread across the Caribbean, it fueled massive growth in African slavery. The Caribbean Islands were inhabited when the Europeans arrived, the most numerous occupants were the Arawaks (or Tainos) who were found across most of the Greater Antilles (Cuba, Jamaica, Hispaniola, and Puerto Rico), and the Caribs who resided in the Lesser Antilles. Within a few decades of the arrival of Christopher Columbus (1451-1506), the Tainos were almost extinct due to brutal, cruel treatment, and susceptibility to the diseases brought by the Europeans.

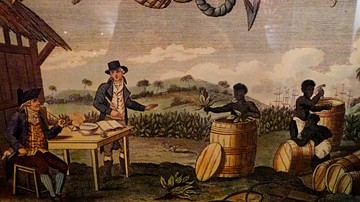

Cocoa was the second plantation crop to emerge in Brazil after sugar. It grew naturally in abundance in the Brazilian Amazônia and the Grão Pará and Maranhão territories. Until about 1640, the cocoa consumed by Europeans was harvested from the wild in northeastern Brazil by Túpi labor gangs run by Jesuit missionaries. The first cocoa was also cultivated by the Jesuits in their missionary gardens in the colonial capital city, Salvador de Bahia in the second half of the 17th century along with sugar cane. In 1679, Peter II of Portugal (r. 1683-1706) issued a directive that encouraged all Brazilian landowners to plant cacao trees on their property, and the first cocoa plantations were begun in southern Bahia using slave labor. Cacao cultivation became of foremost economic importance to Bahia and Amazonia in equatorial Brazil, both under Portuguese colonial and, after 1823, Brazilian independent rule. As with sugarcane, African slaves played the central role in the gathering and processing of this commodity.

Tobacco became an important plantation crop in North America in the 16th century. A Dutch trader brought the first 20 African slaves in 1619 and many more followed as the Dutch were more than willing to trade slaves for tobacco that they could profitably sell in Europe.

As the British factories' insatiable need for raw cotton grew during the Industrial Revolution, US cotton production kept pace by expanding from the original British colonies of South Carolina, Virginia, and Georgia into the vast, rich Mississippi Delta. By the early 1800s, cotton-growing was king in the southern US, and the surplus slave populations of the southeastern tobacco states were relocated.

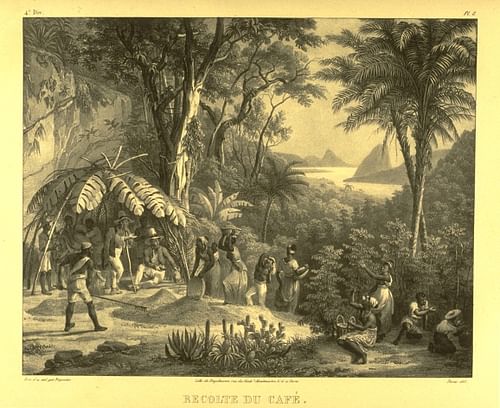

Coffee also became a major crop in Brazil at about the same time as cotton in the US, and by 1850, coffee had almost displaced sugar in the São Paulo region. By that time, four times more slaves were toiling on coffee than sugar. After the mid-1800s, the Brazilian plantation owners began to entice poor Europeans (mostly Italians) to come and work the plantations as colonos or sharecroppers. They were given a home, a little land to grow their own crops, and assigned a number of coffee trees to tend, harvest, and process. The colonos were, in fact, indentured servants who were required to pay off the cost of their transportation and any cash advances before they could leave the plantation. Most plantations had armed guards who kept the sharecroppers in place and in line.

The immigrants initially came in a trickle of thousands from 1850 to 1870, but between 1884 and 1914, over a million arrived. The Brazilian government greatly encouraged this migration, by starting to cover the costs of their transportation in 1884. Under the colono system, coffee production boomed in Brazil, going from 5.5 million bags in 1890 to 16.3 million in 1901.

Africa (1820 -1910)

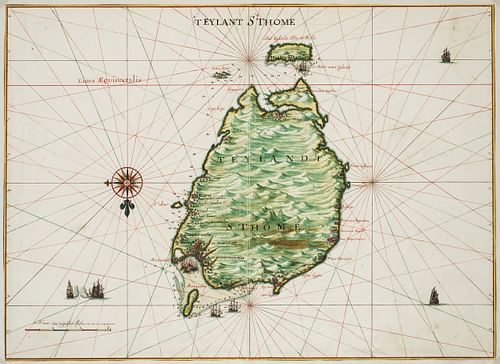

Coffee and cocoa were introduced to São Tomé and Príncipe as plantation crops (rocas) from Brazil, just a few years before the country gained its independence from Portugal. The islands had a prosperous sugar industry until the 1600s Brazil had eclipsed it. In the interim, São Tomé and Príncipe had become a major entrepôt of African slaves captured on the mainland. Initially, coffee received the most attention, but coffee could only be grown at the higher elevations, leaving much of the richest farmland underutilized. Cocoa plantations steadily grew throughout the 1800s, and by the end of the century, São Tomé was the world's largest producer of cocoa. Some 70,000 slaves were brought to São Tomé between 1880 and 1908 from nearby Africa. When slavery was legally abolished in 1875, the Portuguese shifted to contract workers from Angola, Cape Verde, and Mozambique. Unfortunately, the living and working conditions of these indentured laborers were little better than the slaves.

Filling the islands’ plantation labor quota was achieved through three primary methods:

- inducing illiterate Africans to "sign" long-term indentured labor contracts

- manipulating the colonial penal system to allow for the deportation of petty criminals to São Tomé and Príncipe as convict laborers

- slave purchases in Portuguese Africa masked by corrupt bureaucrats who turned a blind eye in return for financial gain.

The result was the creation of a captive workforce on São Tomé and Príncipe that differed from chattel slavery only in name, not in effect.

Indonesia (1870-1950)

While plantation agriculture was booming in the Americas from the early 1500s to the mid-1800s, this system of agriculture was largely ignored in Asia. The Portuguese, Dutch and British were much more focused on forcing the local smallholders to provide them with commodities than building large farms to produce their own crops. The Dutch in particular took control of large production areas of nutmeg, clove, sugar, and coffee through a corvée system of slavery.

As the sugar industry in the Caribbean waned as slavery was abolished in the 1830s, the Dutch seized this opportunity to build a vast cultivation system in Java to produce sugar, and millions of the local people were forced to work in sugar processing and transport. The system became massive; and at one point in the mid-19th century, sugar production in Java accounted for one-third of the Dutch government’s revenues and 4 percent of Dutch GDP. Java became one of the world’s most financially lucrative colonies.

In 1870, an Agrarian Law was passed in the Dutch Republic that abolished forced labor and allowed private companies to lease land in sparsely populated areas. This led to widespread international investment in large plantations and a great expansion in the late 1800s of coffee, tea, and tobacco production in western Java and nearby Sumatra. Rubber, palm oil, and sisal joined these crops at the turn of the century.

Over time the labor pool shifted from forced family units to indentured servants. The plantations of Indonesia came to rely on the mass recruitment of illiterate peasants from Java and Singapore, who were technically free to sign on and were also paid for their labor. However, once they had signed on, they had no say in where they were taken or what kind of work they would have to do. Some wound up in the Caribbean, where it was impossible for them to ever save enough money to pay for their return home. They were used for extremely hard labor, and if they fled this, they were severely punished. The plantation owners used a wide array of ploys to force them to sign new contracts including making loans, encouraging betting losses, and providing alcoholic drinks and even opium.

India & Sri Lanka (1840-1920)

In the 1840s, the British found tea grew well in the Kandyan Highlands of Sri Lanka, and they began clearing the rainforest to form plantations. The British planters used the local Sinhalese villagers as their labor force to clear the forest but turned to the Tamil people of southern India as indentured workers ("coolies") to harvest their crops. The workers were recruited by "sirdars" who also worked in the plantations and were sent back to their home villages with a little money to entice prospective recruits. Upon arrival, the coolies were organized into work gangs under a "kangany" who served as an intermediary between the plantation management and workers. Kanganies were paid a daily bonus for each worker that came to work and often were the paymasters.

The British began establishing massive tea plantations in India by the mid-1800s, and in the late 1800s in nearby Sri Lanka (then known as Ceylon). When a coffee rust started to decimate this acreage that distressed plantation owners began to turn their eyes towards tea and then rubber. The first significant acreages of rubber (hevea) were established at the turn of the 18th century in Sri Lanka and the Malay Peninsula, and by 1912, there were over a million acres of it.

Several systems of labor recruitment emerged, including day hiring of locals and others from away. However, the labor pool was too small and flexible to meet the constant demands of the plantation. It became much more popular to hire contract or indentured workers from distant localities, where famine, overcrowding, or poverty made people desperate for employment. The major recruitment points were first in China followed by India and to a more limited extent Java. In Australian Papua and New Guinea, the plantation owners were reluctant to import so many Chinese and Indians and instead legislated a tax on the locals, forcing them to work on the plantations because they had no other source of cash.

Central America (1860-1920)

In the 1860s, it was discovered that coffee was well adapted to the Verapaz highlands of the Pacific coast of Guatemala, and numerous huge plantations were established across land long occupied by Mayans who were subsequently forced to harvest the coffee. Even those who had moved to the altiplano to avoid the colonists were forced to migrate down to the coffee fields during the harvest season. Many died of influenza and cholera, and those that survived took the diseases back to their villages. The people of Guatemala took to guerrilla warfare but were hunted down and murdered by the troops of President Barrios (in office 1873-85); those who helped the rebels were forcefully resettled. The whole country of Guatemala became almost a penal colony, dominated by a huge standing army and local militias, but the coffee economy of Guatemala boomed.

Coffee economies were also built on the forced labor of indigenous people in Mexico, El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Honduras. Only in Costa Rica were the natives not the primary workforce, as most Mayans had already been exterminated during the Spanish invasion. Similar to Guatemala, most of the countries in Central America became bloody battlegrounds, when the oppressed Mayans rebelled.

Sisal (Agave sisalana) or Henequen also became a major crop in northwestern Yucatan in the mid-19th century when what had been cattle haciendas began planting it for export to the USA. Their henequen industry was responsible for creating a slave-like labor system where workers were held by debt peonage and were banned from leaving their employers. Their major labor pool was again the desperately poor local peoples. In 1840, one-third of these people lived on haciendas, but by 1910, 75 percent of rural Yucatecan residents were living there.

Laborers at henequen haciendas were given rent-free housing and employment, but their wage was rarely enough to cover their expenses. Throughout the 1840s, these laborers were paid 16-17 cents per day in food and wages and quickly became indebted as they were charged for most of their other necessities. This debt bound them to the haciendas, and they were forbidden to leave. In 1882, the government of Yucatán passed a law that stated that if a worker escaped and another hacienda owner harbored him, that hacienda owner could be subject to arrest. This gave rise to bounty hunters in Yucatán.

As the 20th century dawned, Central America also began producing bananas on plantations for the US market and other Western nations. Huge multinational fruit companies, such as Dole, Del Monte, and Chiquita, essentially took control of operations in Latin America, gaining control over much of the farmlands, and manipulating government officials. The workers hired to man the plantations were landless peasants, who were paid better wages than those toiling on sugar and coffee plantations, but they were treated almost as slaves. The field managers acted almost as overseers, many being from the southern US, carrying fond memories of slavery before the Civil War. As the century progressed, banana workers became increasingly restive about their brutal work conditions. Thus began a long tortuous history of violent labor unrest and bloody reprisals by the banana companies, local dictators, and even the US military. Throughout the 1920s, labor unrest spread to all of the Republics of Central America.

Indonesia & Malaysia (2000-today)

In the 21st century, indigenous people and indentured servants are being forced again to harvest coffee, rubber, cassava, and especially oil palm, following the age-old blueprint of plantation agriculture. Palm oil is now found in probably half of the processed food and household products in the United States, Canada, Australia, and Europe. There has been a rebirth of plantation agriculture in Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar (CLM) and the large islands of Sumatra, Borneo, and New Guinea, driven by the same factors as a century ago - high commodity prices and access to cheap land.

Vast tracts of tropical rainforest are being ravaged to make way for oil palm plantations in the two largest palm oil-producing countries, Indonesia and Malaysia. Bird and butterfly species diversity has dropped by 75% where this devastation has occurred, and Orangutans and Sumatran tigers are on the verge of extinction. As plantations systematically replace the rainforest, the local people who had relied on them have no choice but to work on the plantations. They toil under hot, degrading conditions for meager salaries that barely allow them to support their families. In many cases, their children join them in their backbreaking labors without pay. Local governments are doing little to combat this human and environmental exploitation, enjoying the graft and profits flowing from the oil palm industry.

The widespread growth of the plantation system is not restricted to oil palm. Stimulated by the exponential growth of the biofuel industry, large corporate entities are currently buying huge swaths of land in Guatemala, Malawi, Mozambique, and elsewhere to establish sugar cane plantations. These so-called land grabs rely on government support to displace indigenous people and destroy the native habitat. These large-scale land acquisitions present short-term benefits to the local communities in the form of jobs and capital for rural development but destroy local social systems and make them dependent on outsiders for their livelihood. And so, history repeats itself. The expansion of the plantation system today is following the same script played out in the past, starting with sugar cane in the 1600s, banana, tobacco, cotton and coffee in the 1700s, and tea and rubber in the 1800s.