The buccaneers who roamed the Spanish Main and the pirates who plundered the Caribbean and the Indian Ocean during the Golden Age of Piracy (1690-1730) needed a place of refuge where they could share out and enjoy their loot. Pirate havens like Port Royal on Jamaica, Tortuga on Hispaniola, and New Providence in the Bahamas provided safe harbours, the possibility to sell looted cargo to crooked traders, and were within easy reach of the main shipping routes. As the colonial authorities finally got a grip on piracy from 1720 onwards, so the pirate havens declined, many of them becoming a pirate’s very last port of call: the place of their execution.

The Lure of the Pirate Dens

Pirates needed safe harbours where they could hide from the authorities and share out their loot. Ideally, a base was close to the routes taken by merchant shipping, the pirates’ primary target, and, even better, close to a strait where these ships were obliged to navigate through. It also needed to be a place of refuge during the winter or storm season. Pirates needed to be able to repair their ships, and so a base with shallows was ideal as a vessel could be more easily careened. Such locations had the added advantage that large naval vessels could not easily access them.

The havens were a safe place for pirates to rest their weary sea legs and let their hair down. Here they quickly spent their ill-gotten loot on wine, women, and gambling. Pirates sold captured cargoes to unscrupulous dealers who had set up business in the various pirate havens in the Caribbean and the Indian Ocean. The dealers were on to a good thing since they acquired goods at a much cheaper rate than from legitimate merchant vessels in any other port, and the pirates were happy enough to get their cash, even if they were obliged to sell at a price much below the real value. The dealers then smuggled their dubious goods into legitimate ports where it was sold through the channels it would have reached if the pirates had not interrupted the trade process.

Pirates struck deals with corrupt colonial officials if they could, getting a better price for their plunder than they would have in a haven. Perhaps the most infamous of the rotten governors was Charles Eden, governor of North Carolina, who gave such notorious and unrepentant pirates as Edward Teach (aka Blackbeard, d. 1718) and Stede Bonnet (d. 1718) pardons, even allowing the former to establish a pirate base at Ocracoke Island. Another infamous governor who fenced loot for pirates was Colonel Benjamin Fletcher in New York before his dismissal in 1698.

Barbados

Leading up to the Golden Age, piracy had already been rife in the Caribbean for some time. Barbados and St. Kitts were the first British possessions in the West Indies, and they were used for their very remoteness as a useful place to deposit undesirables, ensuring very few would ever be able to make it back to the homeland. During and after the English Civil War (1642-51), Oliver Cromwell sent Irish and Welsh captives to the Caribbean as indentured servants. The lack of any real apparatus of colonial government meant the islands became almost entirely lawless until around 1720 when the governors began to actively pursue such pirates as Bartholomew Roberts (c. 1682-1722).

Ile-a-Vache

Ile-a-Vache ('Cow Island') was a pirate haven off the southwest coast of Haiti used by many French pirates and by Sir Henry Morgan (c. 1635-1688), the most successful of all buccaneers (privateers and pirates who targeted enemies of their state).

Madagascar

Located some 250 miles (400 km) off the coast of southern Africa, Madagascar was the most important pirate haven in the Indian Ocean (others included nearby St. Mary’s Island, Johanna Island, Mathelage, Réunion Island, and Mauritius). The British had attempted to take control of Madagascar but failed in 1645, as did the French, abandoning their efforts in 1674. Caribbean buccaneers began to use Madagascar as a base from the 1680s as they realised the potential for piracy against Indian Ocean ships.

Although inhabited, the pirates benefitted from the ongoing tribal warfare that meant no single indigenous group dominated the island and so sought to remove the foreigners. On the contrary, pirates were welcomed as a source of firearms and as customers to buy or traffic slaves. Pirates were able to make good use of the many hidden harbours on the island which was also rich in freshwater, meat, and fruit. From here, pirates attacked the treasure ships of the Portuguese Empire as well as the rich pilgrim ships of the Indian states. There were also plenty of heavily-loaded merchant vessels sailing back to Europe from Asia, most of them owned by the French, Dutch, and British East India Companies.

At the beginning of the 17th century, there were around 1,500 pirates on the island. Famous Golden Age pirates who used Madagascar as a base of operations at one time or another in their careers of crime included Henry Every (b. 1653), Edward England, Thomas Tew, and Captain Kidd (c. 1645-1701). When piracy became much more difficult thanks to an increased presence of the British Royal Navy, most pirates became settlers on the island, although not with any great success. Visitors in 1711 noted that the European communities there were greatly impoverished, a far cry from the romantic image promoted by the British press and literature of pirate kings living a life of luxury and wanton abandon on a tropical isle.

New Providence, Bahamas

New Providence harbour on New Providence Island took over from Tortuga as the region's main base for pirates. The small island reached its peak as a pirate haven from the 1670s, first for buccaneers chased out of Jamaican waters and then, from around 1713, for pirates who attacked anybody they fancied regardless of nationality. There were good harbours, and plenty of freshwater, meat, timber, and fruit on the island. The main city was called Nassau from 1695. Such pirates as Blackbeard, Jack Rackham (d. 1720), Benjamin Hornigold (d. 1719), and Samuel Bellamy (d. 1717) used the island as a base. In total, there were some 600 pirates sailing from Nassau who raided shipping and ports from the Caribbean to Maine.

From 1718, Governor Woodes Rogers (1679-1732), a staunch enemy of piracy, rebuilt the fortress and stationed cannons at strategic points in the harbour to ward off any pirates thinking of returning. The Bahamas suffered another period of neglect under Rogers’ successor and became a minor pirate haven again until full colonial control was re-established.

Petit Goâve

Petit Goâve was a port on the southwest coast of Saint Domingue (modern Haiti). It attracted buccaneers from the 1670s after the decline of Tortuga and was particularly popular with French pirates and the notorious Dutchman Laurens de Graff since it was far from the (non-corrupt) French colonial authorities yet close to the Spanish Main. By 1700, the buccaneers had been replaced by outright pirates, and Petit Goâve became a mere footnote in French affairs in the Caribbean.

Port Royal, Jamaica

Port Royal was the main port of Jamaica, a British possession from 1655. Known in its early days by its Carib-Spanish name Cayagua ('Water Island') and then anglicized as Cagway, it was given a powerful fortress by the British, but the withdrawal of the Royal Navy left it exposed to Spanish warships. From 1657, Governor Edward D’Oyley, encouraged buccaneers of several nationalities to make the harbour their base and concentrate their plundering on Spanish ships, issuing letters of marque as authority to do so. England’s war with Spain ended in 1660, but many of the buccaneers continued their attacks on legitimate shipping. Subsequent governors were wont to encourage piracy since the presence of many well-armed ships in the harbour significantly lessened the threat from Spain, the Netherlands, and France.

Port Royal became a pirate hotspot in the second half of the 17th century simply because it was so far from the authorities in London and those officials on the island were more pragmatic. Its advantages included a naturally protected harbour that could hold up to 500 ships and a strategic location right in the middle of the Caribbean-Americas shipping routes.

Buccaneers like Sir Henry Morgan, who repeatedly attacked Spanish ships and colonial ports, were based on Jamaica. Morgan was even appointed Lieutenant-governor in 1675. Port Royal became awash with goods and riches, so much so, one contemporary author described it as having more cash than London. By 1680, the haven’s prosperity is evidenced by the presence of over 100 taverns. There were, too, so many gaming houses and brothels that a visiting clergyman described Port Royal as "the Sodom of the New World" (Breverton, 260) in reference to the biblical city infamous for its debauchery. This clergyman did not even bother to stay but returned to England on the very same ship on which he had arrived "since the majority of its population consists of pirates, cut-throats, whores and some of the vilest persons in the whole of the world, I felt my permanence there was of no use" (ibid).

In 1681 the Jamaican authorities finally outlawed piracy, and the pirates moved to other havens such as New Providence. Port Royal was destroyed on 7 June 1692 by a combination of earthquake and tsunami. Several thousand people were killed in the disaster. Although half of Port Royal slipped forever into the ocean, the spot would eventually return to prominence as a place where several notorious pirates were hanged and operate as a British naval base.

Providence Island

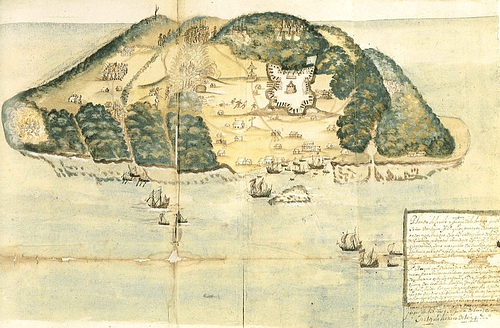

Providence Island, aka Isla de Providencia, and neighbouring Santa Catalina are islands off the coast of Central America used by pirates for their strategic location smack in the middle of the Cuba to Venezuela shipping routes. Providence Island had a good harbour, which was easily defended from its high cliffs. It was first settled by the English from 1630. As elsewhere, piracy was encouraged since it brought trade and a means of defence against Spanish attacks. Indeed, the islands came under Spanish control from 1641 to 1666, and it was not fully out of Spanish hands until Sir Henry Morgan used Providence as a base for his attacks on Panama in 1670 and 1671.

Rhode Island

The ports of Providence and Newport on Rhode Island were used as pirate havens in the second half of the 17th century and the first decades of the 18th century. They hosted such infamous criminals as Blackbeard, Henry Every, and Thomas Tew. Following less corrupt and sterner governance, Rhode Island lost its appeal to pirates, especially following a number of trials and public hangings.

Tortuga, Hispaniola

Tortuga (Ile de la Tortue), located in northwest Hispaniola (modern Haiti and the Dominican Republic), received its name for the resemblance of the island to a turtle when seen from afar. The island became a haunt of cattle hunters and then a pirate base of significance in the mid-17th century when French buccaneers chose it for its proximity to the major regional shipping routes. The base had the additional advantage that there was plentiful meat from cattle and pigs introduced there by early Spanish settlers, and if necessary, the pirates could retreat to the interior’s mountains, as they did when Spanish forces attacked from Santo Domingo in 1630-1631, 1635, and 1638.

In 1642, the French authorities on St. Kitts appointed Jean Le Vasseur, a nobleman and gifted engineer, as the governor of Tortuga, but he struck out on his own, built a fortress that bristled with more than 40 cannons, and declared his colony independent. For the next decade, Tortuga became the most important buccaneer/pirate haven in the Caribbean. Le Vasseur grew rich from his handsome cut of all pirate business in his mini-state. A Spanish force again tried its luck in 1655, but an English fleet rescued Tortuga, and both French and English settlers were welcomed. The pirates had not gone away, though, and continued to be attracted by the advantages of the base. The French took over again in 1665, but they realised the pirates were an excellent deterrent to the Spanish and so left Tortuga pretty much as it was, concentrating instead on colonising the other side of Hispaniola, Saint Domingue. Francois L’Olonnais (1630-1668) famously used Tortuga as a base from which to attack Venezuela in 1667. The island was repeatedly attacked by French and Spanish forces in the 1670s and so many pirates moved on to Petit Goâve by the close of the century, even if a few pirates remained loyal to Tortuga until piracy was banned there by the French authorities in 1713.

Another place with a similar name was used by pirates as a place of repose and from which to attack merchant vessels: the Dry Tortugas, a series of shoals of the Florida Keys.

The End of the Havens

When the authorities, pressured by legitimate businesses and shipowners, shut down havens like New Providence in 1718, piracy in the Caribbean became much more difficult as there was nowhere to sell stolen goods. In the 1710s, colonial Governors like Woodes Rogers in the Bahamas were sent out from London specifically to wipe out piracy in their jurisdiction. The new wave of governors in the Caribbean and the colonies on the eastern coast of North America had both a carrot and stick to achieve their brief. The stick was naval warships, informants, and the hangman’s noose, while the carrot was a royal pardon from King George I of Great Britain (r. 1714-1727) and the promise of land and work in the colonies.

The British government was greatly concerned that piracy was so rife it was driving out honest settlers from its colonies and leaving them so unpopulated they were becoming a great temptation for foreign powers to take over. Many pirates did accept a pardon, but some did not, notably Jack Rackham, Charles Vane, and Edward Teach, but such men were living on borrowed time, and either the Royal Navy or the hangman would get their men soon enough. While some places did suffer economically with the withdrawal of pirates and the trade they brought, the greater presence of the Royal Navy in the Atlantic, the East India Company in the Indian Ocean, and the eradication of corrupt or lapse governors meant piracy became a much more difficult living to earn as the 18th century wore on. In addition, many buccaneers, pirates, and smugglers had done so well out of piracy that they had by now invested their gains in legitimate businesses and plantations. The colonies were no longer the lawless Wild West places they had been as ports and towns finally gained in stature and respectability when institutions of law and justice were firmly established. These colonies came to more closely resemble the communities of the home countries that had first sent out settlers, and the pirates now bothered no one except fiction writers.