The spices clove, nutmeg, and mace originated on only a handful of tiny islands in the Indonesian archipelago but came to have a dramatic, far-reaching impact on world trade. In antiquity, they became popular in the medicines of India and China, and they were a major component of European cuisine in the medieval period. European countries fought mightily for control of the spice trade.

Natural History

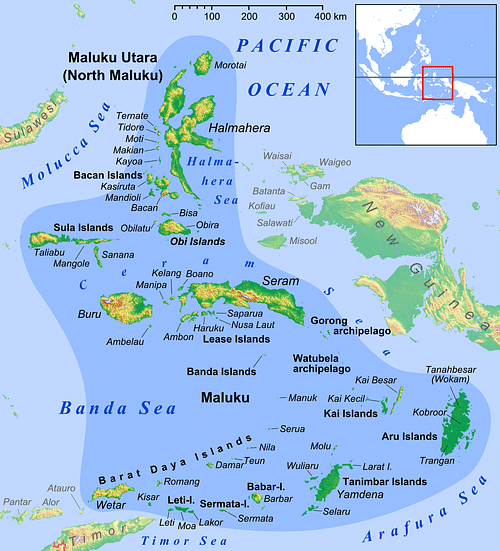

The name clove refers to the dried, unopened buds of the evergreen tree, Syzygium caryophyllata in the myrtle family. Cloves were native to only five tiny, volcanic islands in the East Indian Archipelago: Ternate, Matir, Tidore, Makian, and Bacan, all belonging to the Maluku Islands or the Moluccas.

The nutmegs are the dark reddish-brown seeds within the fruits of Myristica fragrans, of the Myristicaceae family. These seeds are surrounded by a deep red, fleshy net-like membrane, or aril, which is the mace. The nutmeg tree was native to sheltered valleys on the hot, tropical Banda Islands in the Maluku region of Indonesia.

Clove in Antiquity

The first mention of clove is in the Chinese literature of the Han period, around the 3rd century BCE. The spice called hi-sho-hiang ("bird’s tongue") was first used as a breath freshener; officers of the court were required to place cloves in their mouth before discussions with their sovereign. Cloves were used much more widely in medicines than food preparation. They were considered an internal warming herb, which helped dispel cold and warm the body. They were used as tonics and stimulants and were prescribed as a digestive aid and antiseptic. Cloves were used to treat a wide range of ailments including intestinal distress, impotence, diarrhea, vomiting, and cholera. They were made into a poultice to treat cracked nipples, scorpion stings, toothaches, and pretty much any abscess that caused pain.

Cloves also played an important role in ancient Indian society, although they arrived there several centuries later than in China. Cloves became popular in traditional Ayurvedic medicine and were used to treat a wide range of problems including colds, asthma, indigestion, vomiting, toothache, laryngitis, low blood pressure, and impotence. In the ancient Sanskrit text, Charaka Saṃhita (1st century CE), it is stated that "one who wants clean, fresh, fragrant breath must keep nutmegs and cloves in the mouth" (Dalby, 50).

The Roman writer Pliny the Elder (23-79 CE) was the first to describe cloves in the West in his Natural History (70 CE) where he recorded that "there is also in India a grain resembling that of pepper but larger and more fragile, called caryophyllom, which is reported to grow on the Indian lotus tree; it is imported here for the sake of its aroma". Roman emperor Constantine the Great (r. 306-337 CE) is said to have presented Saint Silvester, the bishop of Rome (314-335 CE), with gold and silver vessels filled with incense and spices, including 150 pounds (68 kg) of cloves. The Greek physician Paul of Aegina wrote in the 5th century CE: "It is of the nature of a flower of some tree, woody, black, almost as thick as a finger; reputed aromatic, sour, bitterish, hot and dry in the third degree; excellent in relishes and other prescriptions" (Dalby, 50). In his 6th-century CE Twelve Books on Medicine, the eminent Byzantine physician Alexander of Tralles recommended cloves for seasickness, gout, and appetite stimulation.

Nutmeg & Mace in Antiquity

Nutmeg and mace are frequently mentioned in the oldest scriptures of Hinduism in India, the Vedas, composed between 1500 and 1000 BCE. Nutmeg was recommended for improved digestion and was prescribed for headache, neural problems, fevers from colds, bad breath, and digestive problems. Later Indian texts described nutmeg as an important medicine for cardiac complaints, consumption, asthma, toothaches, dysentery, flatulence, and rheumatism.

Nutmeg and mace’s arrival in China was much later than in India; the first reference of what could have been nutmeg does not appear until the 3rd century CE in Ji Han’s Nanfang Caomu Zhuang (Record of Southern Plants and Trees). In it, he mentions a fragrant spice that comes from a tree whose flowers are colored like a lotus. Nutmeg is not commonly mentioned in the Chinese literature until the 8th century when it is used to treat diarrhea, dysentery, abdominal pain and bloating, reduced appetite, and indigestion.

Nutmeg and mace were largely unknown to the West until the 5h or 6th century CE. Pliny was the first to write about a tree he called comacum, which had a fragrant nut, but it is not certain if he was really referring to nutmeg. The 1st-century CE Greek physician Dioscorides also vaguely refers to a red bark of unknown origin called macir. The first clear references to nutmeg and mace are not found until the Byzantine medical texts of the 6th century, which refer to a red bark, macis (mace), and a musky nut, nux muscata (nutmeg).

Nutmeg, Mace & Clove in Arabian Medicine & Cuisine

The study of medicine was a major focus of Islamic scholars. During the 9th century and into the 10th, Harun al-Rashid of the Abbasid Caliphate and his son collected works of Greek medicine and other scientific texts from throughout the civilized world. These were taken to the Grand Library of Baghdad, the "House of Wisdom", where the entire body of Greek medical texts, including all the works of Galen, Oribasius, Paul of Aegina, Hippocrates, and Dioscorides, were translated into Arabic. Based on their studies, Muslim physicians believed that sickness was the result of bodily imbalances, and these imbalances could be restored if the diet consisted of the right balance of herbs and spices including nutmeg and clove. These spices played a prominent role in the 9th-century medical texts written by the famous Arab physician, Isaac ibn Amran. His works, written in Arabic and translated into Hebrew, Latin, and Spanish, became the foundation of the medical curriculum of medieval Europe.

The Arabs were the first to use cloves and nutmeg extensively in food preparation. In fact, spices were greatly appreciated all across the Middle East for their fragrance and medicinal properties, as well as for their enhancement of flavor in food. Herodotus, the ancient Greek writer, geographer, and historian, wrote in the 5th century BCE of the spices of Arabia that "the whole country is scented with them, and exhales an odor marvelously sweet" (The Histories, Book III). The Iraqi Ibn Sayyar al-Warrag listed cloves repeatedly in his 10th-century Kitab al-Tabikh (The Book of Cookery), the earliest known Arabic cookbook. In his highly regarded Al-Qanun fi al-Tib (The Canon of Medicine, 1025), Ibn Sina recommended "three-eighths of a dram of nutmeg with a small quantity of quince-juice" for "weakness of the stomach," and he described nutmeg as a potent anesthetic concoction. Cloves and nutmeg played a dominant role in the popular, 13th-century Syrian cookbook Kitab al-Wuslah ila l-Habib and in an anonymous Andalusian cookbook.

Nutmeg, Mace, & Cloves in European Cuisine

Before about the 12th century, medical practice in Europe was far behind the Muslims as there was little research being conducted, and because the medieval church considered disease a punishment from God, doctors could do little for their patients. It was not until new translations, observations, and methods of the Islamic world became available that western medicine began to move forward. Insights and methods from Islamic doctors brought many new advances to European medicine, including the widespread treatment of disease with spices.

It is a bit hazy when nutmeg and cloves moved from the medicine cabinet into European cuisine, although their purported 'hot' and 'humid' properties were recommended for centuries in wintertime meals, according to the ancient teachings of Galen. In 716, the Frankish king Chilperic II is known to have granted the monks of Corbie Monastery a toll exception on their annual spice allotment of 30 pounds pepper, five of cinnamon, and two of cloves. There are records from the medieval monastery of St Gall in Switzerland that monks used cloves to season their fasting fish in the 9th century. In the 10th century, Andalusian traveler Ibrahim ibn Ya’qub noted that the burghers of Mainz (Germany) used cloves to season their food. When the king and queen of Scotland celebrated the Feast of the Assumption in 1256, their food was spiced with 50 pounds each of ginger, pepper, and cinnamon, 4 pounds of cloves, and 2 pounds each of nutmeg and mace. At the marriage of the Duke of Bavaria-Landshut in 1476, the banquets required 205 pounds of cinnamon, 286 pounds of ginger, and 85 pounds of nutmeg.

Because of their distant supply lines, the spices were very costly in the Early and High Middle Ages, which restricted them to the wealthy and added greatly to their desirability. However, as the 11th and 12th centuries progressed, there was a steady rise in the popularity of Asian spices, stimulated by the Crusades and those who returned enchanted by the rich cuisine of Constantinople. The Venetians saw a window of opportunity and began to supply the European market with much greater quantities of spice. As Turner comments:

[By the late 12th century,] medieval cooks dreamed up hundreds of different applications, leaving practically no types of food without spice. There were rich and spicey sauces for meat and fish, based on an almost limitless number of combinations of cloves, nutmeg, cinnamon, mace, pepper, and other spices, ground and mixed in with a host of locally grown herbs and aromatics. (105)

The popularity of spices in both cuisine and medicine reached its historical peak during the late Middle Ages in Europe. Food in medieval households was highly processed and richly spiced. Uncooked food was rarely eaten, even vegetables and fruit. The spices were used to season all types of food including meat, fish, soups, sweet dishes, and wine. It even became popular in medieval banquets to pass around a spice platter from which guests could choose extra seasonings for their already richly accented meals. The noted expert on medieval gastronomy, Paul Freedman, tells us that "spices were omnipresent in medieval gastronomy" and "something on the order of 75% of medieval recipes involves spices" (50).

Early Trade of Nutmeg, Mace, & Cloves

Long before nutmeg, mace, and cloves became important to the outside world’s palates and medicines, there was vigorous interisland trade among the Spice Islands and the outer islands of Halmahera, Seram, Kei, and Aru. This trade was centered on the sago palm (Metroxylon sagu), which was the primary food source of the small, volcanic Maluku and Banda Islands, where little else grew but coconut and spices. The Bandanese became the undisputed leaders of the interisland trade of sago for spices, traveling in fleets of kora-kora canoes, propelled by rowers on platforms of bamboo lashed five feet away on either side of the canoe proper.

The sago palm was the staple food of hundreds of thousands of people, but it received little attention from the outside world until 1869, when the great Victorian naturalist and Darwin’s contemporary, Alfred Russel Wallace (1823-1913), described its characteristics at length in his epic The Malay Archipelago. About its taste, Wallace wrote:

The hot cakes are very nice with butter, and when made with the addition of a little sugar and grated cocoa-nut are quite a delicacy. They are soft, and something like corn-flour cakes, but have a slight characteristic flavor which is lost in the refined sago we use in this country …. They were my daily substitute for bread with my coffee. (van Wyhe, 514)

Even with this heavy internal trading of spice for sago palm, the source of nutmeg and clove remained a mystery to the outside world for almost a millennium. Even the Arabians and Indians who sailed all across the Indian Ocean were long clueless about their origin. In the year 1000, the Arabic writer Ibrahim Ibn Wasif-Shah in his Summary of Marvels made this fanciful description about cloves and its source:

… somewhere near India is the island containing the Valley of Cloves. No merchants or sailors have ever been to the valley or have ever seen the kind of tree that produces cloves: its fruit they say is sold by genies. The sailors arrive at the island, place their items of merchandise on the shore, and return to their ship. Next morning, they find, beside each item, a quantity of cloves.

One man claimed to have begun to explore the island. He saw people who were yellow in color, beardless, dressed like women, with long hair, but they hid as he came near. After waiting a little, the merchants came back to the shore where they had left their merchandise, but this time they found no cloves, and they realized that this had happened because of the man who had seen the islanders. After some years absence, the merchants tried again and were able to revert back to the original system of trading.

The cloves are said to be pleasant to the taste when they are fresh. The islanders feed on them, and they never fall ill or grow old. It is also said that they dress in the leaves of a tree that grows only on that island and is unknown to other people.

(Dalby, 50-51)

The entry of the nutmeg and cloves into world trade was long dependent on Malay and Indonesian sailors, with the Javanese being the primary players. As the 1st century CE dawned, three separate trading spheres were operating in the Indian Ocean and the South China Sea:

- Sailors from India and Sri Lanka were traveling to and from Bali, Java, and Sumatra across the Bay of Bengal.

- Indonesian seafarers were conducting trade within the center of the vast archipelago itself.

- Indonesians reached out into Southeast Asia and China.

Trade emporiums arose in Java and Sumatra, where Indian and later Arabian sailors could access all the spices and commodities of Southeast Asia and distribute them across the Indian Ocean. The Indian and Arabian ships typically sailed only as far east as the Strait of Malacca, and Indonesian ships made the other two journeys to eastern Indonesia and China. It was not until the High Middle Ages that Arabian and Indian sailors themselves knew the true home of the spices, clove, nutmeg, and mace.