The Forty-Two Judges were divine entities associated with the afterlife in ancient Egypt and, specifically, the judgment of the soul in the Hall of Truth. The soul would recite the Negative Confession in their presence as well as other gods and hope to be allowed to continue on to the paradise of the Field of Reeds.

The ancient Egyptians have long been defined as a death-obsessed culture owing to their association with tombs and mummies as depicted in popular media and, of course, the famous discovery of the Tomb of Tutankhamun by Howard Carter in 1922 CE. Images of the jackal-headed god of the dead Anubis or the black-and-green mummified form of Osiris have also encouraged this association in the public imagination.

Actually, however, the Egyptians loved life and their seeming preoccupation with death and the afterlife was simply an expression of this. There is no evidence that the ancient Egyptians longed for death or looked forward to dying in any way – in fact, precisely the opposite is abundantly clear – and their elaborate funerary rituals and grand tombs stocked with grave goods were not a celebration of death but a vital aspect of the continuation of life on another, eternal, plane of existence. To reach this idealized world, however, one needed to have lived a virtuous life approved of by Osiris, the judge of the dead, and the Forty-Two Judges who presided with him over the Hall of Truth in the afterlife.

The Afterlife

The Egyptians believed that their land was the best in the world, created by the gods and given to them as a gift to enjoy. They were so deeply attached to their homes, family, and community that soldiers in the army were guaranteed their bodies would be returned from campaigns because they felt that, if they died in a foreign land, they would have a harder time – or possibly no chance at all – of attaining immortality in the afterlife.

This afterlife, known as The Field of Reeds (or Aaru in ancient Egyptian), was a perfect reflection of one's life on earth. Scholar Rosalie David describes the land which awaited the Egyptians after death:

The underworld kingdom of Osiris was believed to be a place of lush vegetation, with eternal springtime, unfailing harvests, and no pain or suffering. Sometimes called the `Field of Reeds', it was envisaged as a `mirror image' of the cultivated area in Egypt where rich and poor alike were provided with plots of land on which they were expected to grow crops. The location of this kingdom was fixed either below the western horizon or on a group of islands in the west. (160)

To reach this land, the recently deceased needed to be buried properly with all attendant rites according to their social standing. Funerary rites had to be strictly observed in order to preserve the body which, it was thought, the soul would need in order to receive sustenance in the next life.

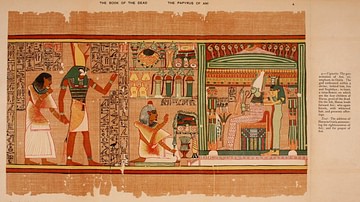

Once the body was prepared and properly entombed, the soul's journey began through the afterlife. Funerary texts inside the tomb would let the soul know who they were, what had happened, and what to do next. The earliest of these were the Pyramid Texts (c. 2400-2300 BCE) which then evolved into the Coffin Texts (c. 2134-2040 BCE) and were fully developed as The Egyptian Book of the Dead (c. 1550-1070 BCE) during the period of the New Kingdom (c.1570-c.1069 BCE). The god Anubis would greet the newly departed soul in the tomb and usher it to the Hall of Truth where it would be judged by Osiris and an important aspect of this judgment was conference with the entities known as the Forty-Two Judges.

The Forty-Two Judges

The Forty-Two Judges were the divine beings of the Egyptian after-life who presided over the Hall of Truth where the great god Osiris judged the dead. The soul of the deceased was called upon to render up confession of deeds done while in life and to have the heart weighed in the balance of the scales of justice against the white feather of Ma'at, goddess of truth and harmonious balance. If the deceased person's heart was lighter than the feather, they were admitted to eternal life in the Field of Reeds; if the heart was found heavier than the feather it was thrown to the floor where it was eaten by the monster Amemait (also known as Ammut, `the gobbler', part lion, part hippopotamus and part crocodile) and the soul of the person would then cease to exist. Non-existence, rather than an after-world of torment, was the greatest fear of the ancient Egyptian.

Although Osiris was the principal judge of the dead, the Forty-Two Judges sat in council with him to determine the worthiness of the soul to enjoy continued existence. They represented the forty-two provinces of Upper and Lower Egypt and each judge was responsible for considering a particular aspect of the deceased's conscience. Of these, there were nine great judges:

- Ra - the supreme sun god in his other form of Atum

- Shu – the god of air and peace

- Tefnut – goddess of moisture

- Geb – god of the earth

- Nut – goddess of the sky

- Isis – goddess of life, fertility, magic

- Nephthys – sister of Isis, goddess of the dead

- Horus – god of the sun and sky

- Hathor – goddess of love, fertility, joy

Of the other judges, they were depicted as awe-inspiring and terrible beings bearing names such as Crusher of Bones, Eater of Entrails, Double Lion, Stinking Face and Eater of Shades, among others (Bunson, 93). The Forty-Two Judges were not all horrifying and terrible of aspect, however, but would appear to be so to that soul who faced condemnation rather than reward for a life well-lived. The soul was expected to be able to recite the Negative Confession (also known as the Declaration of Innocence) in defense of one's life in order to be considered worthy to pass on to The Field of Reeds.

The Negative Confession

The Negative Confession was recited in concert with the weighing of the heart to prove one's virtue. There was no one set verse known as “the Negative Confession” – each verse, included in funerary texts, was tailored to the individual. A soldier would not recite the same confession as a merchant or scribe. The most famous of these is the Papyrus of Ani, a text of The Egyptian Book of the Dead, composed c. 1250 BCE. Each confession is addressed to a different god and each god corresponded to a different nome (district) of Egypt:

1. Hail, Usekh-nemmt, who comest forth from Anu, I have not committed sin.

2. Hail, Hept-khet, who comest forth from Kher-aha, I have not committed robbery with violence.

3. Hail, Fenti, who comest forth from Khemenu, I have not stolen.

4. Hail, Am-khaibit, who comest forth from Qernet, I have not slain men and women.

5. Hail, Neha-her, who comest forth from Rasta, I have not stolen grain.

6. Hail, Ruruti, who comest forth from Heaven, I have not purloined offerings.

7. Hail, Arfi-em-khet, who comest forth from Suat, I have not stolen the property of God.

8. Hail, Neba, who comest and goest, I have not uttered lies.

9. Hail, Set-qesu, who comest forth from Hensu, I have not carried away food.

10. Hail, Utu-nesert, who comest forth from Het-ka-Ptah, I have not uttered curses.

11. Hail, Qerrti, who comest forth from Amentet, I have not committed adultery.

12. Hail, Hraf-haf, who comest forth from thy cavern, I have made none to weep.

13. Hail, Basti, who comest forth from Bast, I have not eaten the heart.

14. Hail, Ta-retiu, who comest forth from the night, I have not attacked any man.

15. Hail, Unem-snef, who comest forth from the execution chamber, I am not a man of deceit.

16. Hail, Unem-besek, who comest forth from Mabit, I have not stolen cultivated land.

17. Hail, Neb-Maat, who comest forth from Maati, I have not been an eavesdropper.

18. Hail, Tenemiu, who comest forth from Bast, I have not slandered anyone.

19. Hail, Sertiu, who comest forth from Anu, I have not been angry without just cause.

20. Hail, Tutu, who comest forth from Ati, I have not debauched the wife of any man.

21. Hail, Uamenti, who comest forth from the Khebt chamber, I have not debauched the wives of other men.

22. Hail, Maa-antuf, who comest forth from Per-Menu, I have not polluted myself.

23. Hail, Her-uru, who comest forth from Nehatu, I have terrorized none.

24. Hail, Khemiu, who comest forth from Kaui, I have not transgressed the law.

25. Hail, Shet-kheru, who comest forth from Urit, I have not been angry.

26. Hail, Nekhenu, who comest forth from Heqat, I have not shut my ears to the words of truth.

27. Hail, Kenemti, who comest forth from Kenmet, I have not blasphemed.

28. Hail, An-hetep-f, who comest forth from Sau, I am not a man of violence.

29. Hail, Sera-kheru, who comest forth from Unaset, I have not been a stirrer up of strife.

30. Hail, Neb-heru, who comest forth from Netchfet, I have not acted with undue haste.

31. Hail, Sekhriu, who comest forth from Uten, I have not pried into other's matters.

32. Hail, Neb-abui, who comest forth from Sauti, I have not multiplied my words in speaking.

33. Hail, Nefer-Tem, who comest forth from Het-ka-Ptah, I have wronged none, I have done no evil.

34. Hail, Tem-Sepu, who comest forth from Tetu, I have not worked witchcraft against the king.

35. Hail, Ari-em-ab-f, who comest forth from Tebu, I have never stopped the flow of water of a neighbor.

36. Hail, Ahi, who comest forth from Nu, I have never raised my voice.

37. Hail, Uatch-rekhit, who comest forth from Sau, I have not cursed God.

38. Hail, Neheb-ka, who comest forth from thy cavern, I have not acted with arrogance.

39. Hail, Neheb-nefert, who comest forth from thy cavern, I have not stolen the bread of the gods.

40. Hail, Tcheser-tep, who comest forth from the shrine, I have not carried away the khenfu cakes from the spirits of the dead.

41. Hail, An-af, who comest forth from Maati, I have not snatched away the bread of the child, nor treated with contempt the god of my city.

42. Hail, Hetch-abhu, who comest forth from Ta-she, I have not slain the cattle belonging to the god.

This confession is similar to others in basic form and includes statements such as: "I have not stolen. I have not slain people. I have not stolen the property of a god. I have not said lies. I have not led anyone astray. I have not caused terror. I have not made anyone hungry” (Bunson, 187). A line which often appears is “I have not learnt that which is not” also sometimes translated as “I have not learned the things that are not” which referred to believing in falsehoods or, more precisely, false truths which were anything contrary to the will of the gods which might appear true to a person but was not.

For example, a man who had recently lost his wife was fully expected to mourn his loss and entitled to a period of grief but, if he should curse the gods for his loss and stop contributing to the community because of his bitterness, he would have been considered in error. He would have “learned the things that are not” by believing he was justified to persevere in his grief instead of being grateful for the time his wife had been with him and the many other gifts the gods gave him daily. The Negative Confession allowed the soul the opportunity to prove it understood this and had lived according to the will of the gods, not to its own understanding.

Conclusion

The Egyptian Book of the Dead provides the most comprehensive picture of the Forty-Two Judges as well as spells and the incantation of the Negative Confession. According to scholar Salima Ikram:

As with the earlier funerary texts, the Book of the Dead served to provision, protect and guide the deceased to the Afterworld, which was largely located in the Field of Reeds, an idealized Egypt. Chapter 125 was an innovation, and perhaps one of the most important spells to be added as it seems to reflect a change in morality. This chapter, accompanied by a vignette, shows the deceased before Osiris and forty-two judges, each representing a different aspect of ma'at. A part of the ritual was to name each judge correctly and give a negative confession. (43)

Once the Negative Confession had been made by the soul of the deceased and the heart had been weighed in the balance, the Forty-Two Judges met in conference with Osiris, presided over by the god of wisdom, Thoth, to render final judgement. If the soul was judged worthy then, by some accounts, it was directed out of the hall and toward the Lily Lake where it would meet with the creature known as Hraf-haf (meaning He-Who-Looks-Behind-Him) who was an ill-tempered and insulting ferryman whom the deceased had to find some way to be kind and cordial to in order to be rowed to the shores of the Field of Reeds and eternal life.

Having passed through the Hall of Truth and, finally, proven themselves worthy through kindness to the un-kind Hraf-Haf, souls would, at last, find peace and enjoy an eternity in bliss. The Field of Reeds perfectly reflected the world one had enjoyed in one's earthly existence, right down to the trees and flowers one had planted, one's home and those loved ones who had passed on before. All an ancient Egyptian needed to do to attain this eternal happiness was to arrive in the Hall of Truth with a heart lighter than a feather after having lived a life worthy of approval by Osiris and the Forty-Two Judges.