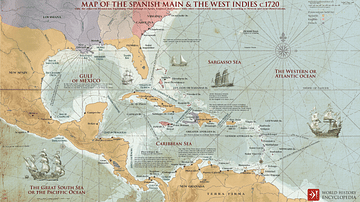

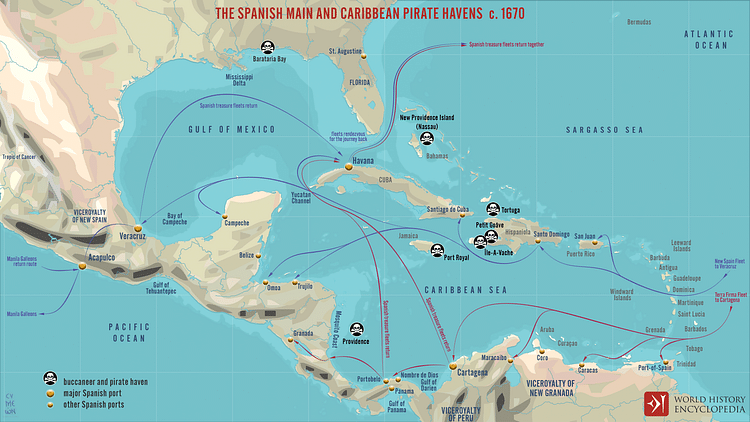

The treasure ports of the Spanish Main such as Cartagena, Portobelo, Panama, and Veracruz were used to collect the riches the Spanish Empire had extracted from the Americas, ready for transport in the two annual treasure fleets back to Europe. The huge quantities of gold, silver, and other precious goods involved made these ports a tempting target for foreign powers and privateers like Francis Drake (c. 1540-1596 CE) and Henry Morgan (c. 1635-1688 CE). The Spanish Crown invested heavily in defensive fortifications, making such ports as Havana and San Juan de Ulúa formidable objectives for even large fleets of rival naval warships.

The Riches of the Spanish Empire

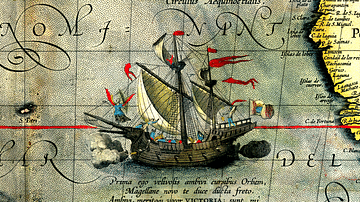

The Spanish conquered such peoples as the Aztecs in Mexico and the Incas in South America in the first half of the 16th century, and they stripped these cultures of anything valuable, melting down objects of gold and silver, in particular. Massive quantities of silver also came from mines which the Spanish took over. This raw silver was frequently minted into pesos or pieces of eight, a coin that became the de facto international currency of the Americas. There were, too, the Manila galleons which shipped precious Eastern goods like silk and spices from the Philippines to Acapulco in Mexico. Treasure ships then transported huge quantities of this loot in annual trips from Mexico and Central America, across the Atlantic to Spain. By 1600, 25,000 tons of silver alone had been transported to Spain. The quantities of loot declined from the 1620s, but nevertheless, the treasure ship convoys continued until the 1730s, with a small fleet continuing from Mexico alone between 1754 and 1789. At their peak, a treasure fleet could consist of up to 90 merchant vessels and at least eight warships.

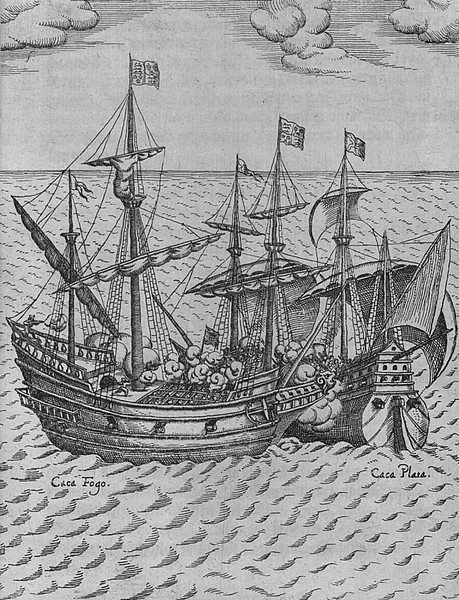

Early privateers like the Elizabethan mariners the Spanish disparagingly called the "sea dogs" did get away with capturing some treasure ships before Spain armed them better. English and Dutch naval fleets also occasionally captured treasure ships at sea in the 16th and 17th centuries, but generally, they were too powerful a target for later pirates and privateers like the buccaneers. In fact, storms and reefs caused much more havoc to the treasure fleets than enemy ships. The Spanish galleons, bristling with cannons, travelled in convoys from 1555 (an idea instigated by Captain-General Pedro Menendez de Avilés) and were additionally protected by a specific task force, the Armada de la Guarda de la Carrera de las Indias. This fleet of 6 to 16 warships was created in 1521 to patrol the waters between the final stretch of the route, the Azores to Spain. From the 1540s, the task force accompanied galleons all the way from the Caribbean to Europe.

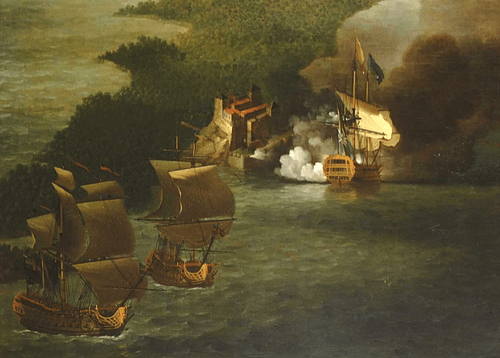

Presented with these difficulties, the other European navies, privateers, and pirates targeted not the mighty treasure fleets but the depots where the riches were accumulated before being loaded onboard galleons: the American treasure ports. Depots like Cartagena, Panama, and Portobelo were persistently targeted by large amphibious forces of multinational buccaneers who were sponsored – either officially or otherwise – by colonial authorities such as British Jamaica and French Hispaniola. The Spanish responded to these attacks from the 1560s and built bigger and better fortifications with suitably enlarged garrisons. Over the next two centuries, though, the Spanish were obliged to continuously defend their crumbling empire against large British, Dutch, and French naval fleets, which now sailed from bases in the Caribbean. The New World had become a theatre of war every bit as dreadful as the European continent had been for two millennia.

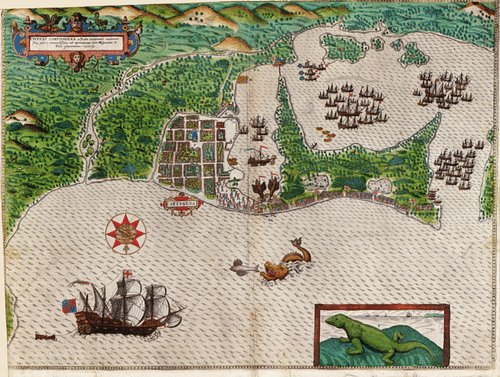

Cartagena

Cartagena, in what is today Colombia, acted as a collecting point for gold, silver, emeralds, and pearls from Colombia and Venezuela. The city, sheltered in a wide deepwater bay, was known as the "Queen of the Indies" (as the Americas were then known). Cartagena, not so well protected in its early days, was attacked by French privateers in 1543. The English privateers John Hawkins (1532-1595) and Francis Drake attacked the port in 1568 and 1586, respectively. Hawkins was unsuccessful, but Drake did capture the town, albeit for relatively little plunder and no ransom. Consequently, Cartagena's defensive fortifications were greatly improved with a massive fortress and bastion built on the narrow spit of land that protected the harbour in 1602. Even if ships avoided the fortresses' many cannons, they would still have to negotiate the narrow channel accessing the harbour with its treacherous shallows and hidden reefs. Even then, additional fortresses like the Castillo San Felipe de Barajas (1647) provided an opportunity for a lethal defensive crossfire. Finally, a circuit wall was built from 1614 and ensured that Cartagena was all but impregnable.

Not even the large armies of the buccaneers took on the challenge presented by Cartagena, but it was finally captured in April–May 1697 when the French combined buccaneers with naval warships to crack the Spaniards' toughest treasure port. The city's weakness had been the isolation of each of its fortresses, and the French had picked them off one by one. Cartagena did successfully resist a British force of 180 ships in 1741. The city's fortifications were again improved from 1769 following the fall of Havana earlier in the decade so that the entire citadel became a maze of massive fortifications and cannon batteries. Colombian rebel forces besieged and took Cartagena in 1815 and 1821.

Havana

Havana in Cuba was not a treasure port as such, but it was the keystone of the Spanish Main and acted as the final departure point for the Atlantic crossing where all the treasure fleets could receive supplies for the voyage. From 1610, Havana was also an important shipyard, building a significant number of Spanish galleons for service in the Caribbean.

The early port, like other Spanish colonies, received a European-style medieval castle, but this was not enough to deter the French privateer Jacques de Sores who brutally attacked Havana in July 1555, although there was next to no gold or silver to be found. As a consequence of this raid, in 1558 Havana received a new and greatly improved defensive fortification, the Fuerza Real, which was the first bastion fortress to be built in the Americas. The great fortress known as the Castillo de los Tres Reyes Magos del Morro ("Castle of the Three Wise Kings"), or simply Morro Castle for short, was built from 1589 to 1630 and was designed by the gifted Italian engineer Bautista Antonelli. The castle boasted many sharp-angled bastions that followed the contours of the rocky east side of the harbour. There were multiple firing platforms for cannon batteries, a curtain wall, and a large outer dry moat, effectively making Havana's narrow harbour entrance a no-go area for enemy ships.

From 1674, a stone circuit wall was built which enclosed the city by the 1690s but which was not finally completed until 1797. The city's defences were manned by ten companies of militia and over 600 regular soldiers, the largest garrison on the Spanish Main and one which increased to a total military force of 6,000 men by the mid-18th century. The garrison protected the town's 30,000 inhabitants and operated the 180 guns mounted along 4.5 km (2.8 miles) of defensive walls.

Havana did fall to a large British force consisting of 200 ships and 11,000 men in August 1762, when the invaders gained the heights opposite the port and relentlessly pounded each fort in turn until they submitted. The occupation was brief, with Havana being returned under the 1763 Treaty of Paris, and so Cuba would remain in Spanish hands until 1898. The fall of Havana led to King Charles III of Spain (r. 1759-1788 CE) investing heavily in improved defences throughout the Spanish Main and particularly at the treasure ports. Western Havana received a new fortress with the design of a five-pointed star, the Castillo de Santo Domingo de Atarés. At the same time, the heights of La Cabaña, which the British had used to bombard Havana, was given the largest fort in the Americas, completed in 1774 at the enormous cost of 60,000,000 silver pesos.

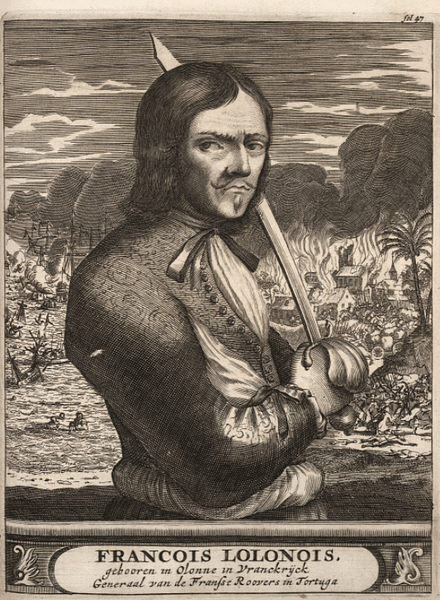

Maracaibo

Maracaibo is on the coast of what is today Venezuela. By the mid-1660s, Maracaibo had around 4,000 residents and was the centre of the regional pearl trade. It was protected by a fortress with 16 cannons, but this did not deter the French buccaneer François L'Olonais (c. 1630-1668), who made multiple attacks on the Spanish Main. L'Olonais' slaughter of his hapless victims earned him a nickname as the "Flail of the Spanish" (Fléau des Espagnols). In 1667, he attacked Maracaibo with a force of 600 men and eight ships. Attacking from the land side and so avoiding the fortress' cannons, the town was captured and looted. L'Olonais then extorted a ransom from the Spanish authorities for the safe return of Maracaibo, and he received 30,000 pieces of eight. Maracaibo was attacked again in April 1669 by another force of buccaneers, this time led by the Welshman Captain Henry Morgan. The town was sacked, and not even three Spanish war galleons could prevent the buccaneers from making off with a fortune in loot.

Panama

The port of Panama, located on the Pacific coast of the Isthmus of Panama, was founded in 1519, and it was where the Spanish gathered the massive quantities of silver they extracted from the mines of South America. The biggest mine was Potosi in Peru (discovered in 1545), which annually produced nine million silver pesos at its peak in 1600; it was still producing a handsome two million pesos in 1700. Panama was at its height around 1607 when there were 6,000 inhabitants (4,000 of whom were black slaves). From here the silver was packed onto mules and taken across the Isthmus of Panama to the Atlantic port of Nombre de Dios (founded 1510). From 1596, the latter, being swampy and plagued with fever-carrying insects, was replaced by Portobelo which had a much better harbour and greater potential for defence.

The fortune in silver that was collected in the isthmus tempted several attacks from privateers. In February 1573, Francis Drake arrived on the scene, describing the moment to his men thus: "I have brought you to the treasure house of the world" (Cordingly & Falconer, 15). Drake seized the mule train taking precious metal to Nombre de Dios and grabbed 15 tons of silver and 100,000 gold pesos (enough cash to build 30 warships of the period). Drake was at it again in March 1579 when he captured the Nuestra Señora de la Concepción (aka Cacafuego), a treasure ship which was taking 26 tons of silver, 13 chests of plate, and 36 kg (80 lbs) of gold from Peru to Panama. Drake was obliged to remove the ballast from his ship, the Golden Hind, in order to find room for these riches.

Not all attacks were successful. The privateer John Oxenham (c. 1535-1580) took control of Panama for a year from 1576, but his ships were destroyed by a Spanish naval fleet. The Englishman was captured, tortured, and executed. The captured members of Oxenham's crew were either hanged there and then or sent to work as galley slaves in Spanish ships.

Following another attack on the isthmus by Drake in 1595-6, Panama was largely left alone until it was hit by a large buccaneer force led by Henry Morgan in January 1671. Having taken the San Lorenzo fortress that protected the Chagres River entrance to Panama and then attacking from the land side, the marauders took over the poorly-defended city – its single fort had a mere six cannons – and Panama was burned to the ground. The locals later rebuilt their port a little way down the coast, a site that eventually became Panama City. The original Panama was abandoned and reclaimed by the jungle.

Portobelo

Portobelo (aka Puerto Bello), in what is today Panama, was one of Spain's big three treasure ports. It was the final depot for the huge quantities of silver gathered from mines in South America, and it was the site of a large annual trade fair. After Francis Drake's final raid, carried out just before his death from dysentery in January 1596, the port was well protected by three separate fortresses bristling with 60 cannons in all. These, however, did not prevent an attack in January 1601 by William Parker (d. 1617).

Aware that Portobelo's defences were poorly maintained and undermanned, Henry Morgan attacked in July 1668. He used 23 canoes to land 500 men a few miles from the town and then marched to surprise the Spanish who were expecting an attack from the sea. After the victory, prisoners were tortured to reveal their valuables and a ransom demanded for the buccaneers to withdraw. The ransom was paid by the Governor of Panama, and along with the loot taken from the city, Morgan made off with 250,000 silver pesos.

Portobelo was attacked several more times, notably in February 1680 by John Coxon and Bartholomew Sharp (d. 1688). Of all the Spanish Main ports, Portobelo seemed an irresistible target to the British, and they again briefly captured it in November 1739 when Vice Admiral Edward Vernon executed his orders to "destroy the Spanish settlements in the West Indies and distress their shipping by any method whatever" (quoted in Wood, 164). As a consequence of this new wave of attacks, Portobelo's defences were again improved in the 1750s and now presented 24 cannons on two levels instead of the previous arrangement of 18 on one level.

San Juan de Ulúa - Veracruz

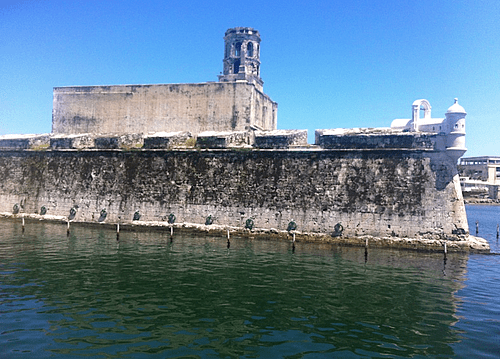

San Juan de Ulúa was the fortress island that protected the harbour of Veracruz on the Atlantic coast of what is today Mexico. Veracruz was founded in 1519 by Hernán Cortés who scuttled his ships so that his men would not be tempted to return home until this part of the Americas was conquered. The wood from these ships was used for Veracruz's first fortification. Veracruz soon became the collection point both for silver gathered from Mexico and the precious eastern goods brought by the Manila galleons to Acapulco and then transported across land to Veracruz. As was typical of Spanish settlements in the Americas, the town was laid out in a regular grid pattern of blocks and streets. It was further fortified by the Spanish from 1535, improved again in 1582 with a stone fort replacing the old one, and it was given a circuit wall in the 1630s, but as the settlement never grew to any significance, Veracruz was not deemed worthy of attack for most of the 17th century. Back in September 1568, John Hawkins and Francis Drake had attacked Veracruz but came off worse when the Spanish treasure fleet sailed into harbour. The new viceroy of the Spanish Empire, Don Martín Enríquez, had infamously offered peace terms to the English fleet but then treacherously went back on his word, an about-turn that the English would use as justification for privateering elsewhere on the Spanish Main for the next 40 years.

The next major attack came over a century later when the Dutch privateer Laurens De Graaf (c. 1651-1702) attacked the port in May 1683 and managed to make off with the loot meant for a treasure fleet. The Spanish responded to this loss by building on San Juan de Ulúa a new two-towered fortification, which bristled with more than 100 cannons. Unfortunately, parts of these walls became so drifted up with shifting sands that it was possible to walk over them, a poignant reminder of the never-ending difficulties the Spanish had in building and, more importantly, maintaining their defensive fortifications across a huge empire.