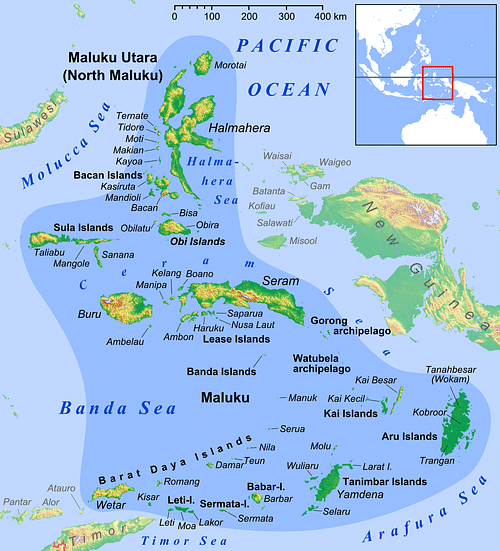

Clove, nutmeg, and mace are native to only a handful of tiny islands in the middle of the vast Indonesian archipelago – cloves on five Maluku Islands (the Moluccas) about 1250 km (778 mi) west of New Guinea, and nutmeg on the ten Banda Islands approximately 2,000 km (1,243 mi) east of Java. Despite their popularity in European cuisine, the origin of the spices was unknown to Europeans until the early 16th century.

The secret was finally broken by the Portuguese in 1512, soon after they discovered the route to the Indian Ocean. After beating back a threat from the Spanish, the Portuguese Empire took over most of the spice trade and held sway for almost a century. Eventually, the Dutch and English made it a three-way struggle for control, which the Dutch won, and they dominated the spice trade until the late 18th century.

The First Europeans on the Spice Islands

For over a thousand years, the entry of clove, nutmeg, and mace into world trade was dependent on Indonesian sailors, who carried them to the Malay Peninsula, Java, and Sumatra, where Indian and Arabian sailors accessed them and distributed them across the rest of the Indian Ocean. The Arabs also carried the spices through the Red Sea to Alexandria or via the Persian Gulf to Levantine ports, from where Venetian traders took them to Europe. The enterprising Arabs held the location of the Spice Islands secret from the Europeans for centuries, keeping the price exorbitant.

It was not until the early 1500s that the Europeans learned whence the spices came, not long after Vasco da Gama (1469-1524) discovered the route around Africa to India and Southeast Asia. The Portuguese Viceroy of India (Estado da India), Albuquerque, was told of the Spice Islands by sailors in the port of Malacca on the Malay Peninsula, which had been for centuries the central meeting ground of Indian, Arab, and Chinese merchants. Albuquerque hired local guides and sent ships on an exploratory mission under the command of António de Abreu and his lieutenant Francisco Serrão. They arrived in the Bandas in 1512 and were able to fill the hulls of their ships with cloves, nutmeg, and mace.

Abreu was then successful in returning to Malacca, but Serrão's overstuffed ship floundered and broke up on a reef. He and his shipwrecked crew were rescued and brought to the Maluku Island of Ternate by the local Sultan Sirrullah, who hoped to use Serrão to ally himself with the powerful Portuguese and tip the balance of power in the area. At that time, Ternate was in fierce competition with the nearby island of Tidor. Serrão became Sirrullah's personal advisor, led a band of mercenaries, and remained on the island until his death.

The second group of Europeans to arrive in the Spice Islands were the remnants of Ferdinand Magellan's (c. 1480-1521) crew after he had lost his life in the Philippines. Their coming began a competition between Portugal and Spain for control of the Spice Islands, whose legal ownership was very much up in the air. The Treaty of Tordesillas, signed in 1494 between the two Iberian countries, had divided any newly discovered lands between them along a meridian west of the Cape Verde Islands but did not establish a line of demarcation on the other side of the world. This meant that both countries could lay claim to the Spice Islands, as long as Portugal traveled there from the east and Spain from the west.

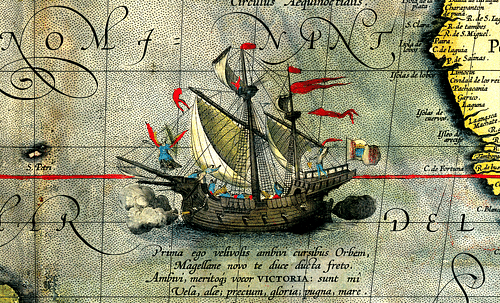

Magellan's remaining two ships sailed on after his death, following a rather haphazard route towards Tidor, and arrived there on 5 November 1521. The Victoria continued towards home on 21 December, while the Trinidad lingered for repairs. Both ships were in dismal condition, and the Victoria barely survived the passage around the stormy tip of Africa, and along the way half its crew died of scurvy and starvation. On 6 September 1522, the remaining crew finally made it back to Spain. By then, only 18 of the original 270 men who had left with Magellan remained. Still, there were enough spices in the hold for the journey to be highly profitable.

The Trinidad, captained by Gonzalo Gómez de Espinosa, waited until 16 April 1522 to leave. Fearing the route around the Cape, the Trinidad made its way north searching for easterlies until the battering of frigid storms, starvation and scurvy forced de Espinosa to turn back to the Maluku Islands seven months later. As he approached Ternate, he found to his horror that a fleet of seven Portuguese ships led by Antonio de Brito had arrived, looking to take control of the Spice Islands.

De Brito sent an armed party to capture the Trinidad:

His soldiers boarded Trinidad expecting to overwhelm the crew but were repelled by the grievous spectacle of men near death, a foul and unhealthy stench that no one dared to brave, and a ship on the verge of sinking. In spite of the crew's condition, De Brito took them as captives and made de Espinosa and his debilitated crew build a fortress at Ternate with the timbers of the Victoria. They were then further exported as forced laborers at several ports across the Indian Ocean. Only commander Espinosa and two other crew members ever got back to Spain. (Bergreen, 180)

The Portuguese on Ternate

The sultan of Ternate allowed the Portuguese to build a fort in 1522 and establish a trading colony, but the relationship between the Ternates and Portuguese quickly grew strained. Over the next half-century, a series of Portuguese governors would be sent to this distant outpost who grew increasingly greedy and brutal. The sultans of Ternate continued to serve at the whims of the Portuguese for decades, but by the mid-16th century began to assert themselves. One major figure was Sultan Hairun who reigned from 1535 to 1570. He started as a Portuguese puppet, and at one point even converted to Christianity, but he became increasingly agitated by the brutality of the Portuguese and eventually aligned himself with the Muslims of Tidor. He was assassinated in 1570 and was replaced by his son Babullah, who led an uprising supported by the Sultanate of Tidor and Muslims from as far away as Aceh and Turkey. He and his followers laid siege to the Portuguese fort and after four years finally took it and rid themselves of the Portuguese. From then on Ternate was a strong, fiercely Islamic, and anti-Portuguese state.

Spanish Efforts

Soon after the arrival of the Victoria in Spain, Charles I of Spain (r. 1516-1556) sent a second expedition to the Spice Islands, led by García Jofre de Loaísa. They were given three goals:

- seek and rescue the Trinidad, which had not yet returned

- colonize the Spice Islands

- find the location of the mythical land of Ophir, mentioned in the Bible as the source of the silver, gold, and gems used to decorate Solomon's Temple.

Loaísa sailed south along the African coastline, then west to Brazil and down the continent before heading to the Spice Islands around the tip of South America. His fleet suffered extreme weather in the Strait of Magellan, and two ships were lost. The raging storms continued in the Pacific and four more ships got separated. Only one galleon, the Santa Maria de la Victoria, reached the Spice Islands in September 1526, and by this time Loaísa had died. The survivors were able to establish a fortress on Tidor but had to abandon their now unseaworthy ship, leaving them no way to get news back to Spain.

With no news of the Loaísa expedition, Charles sent another fleet to the Maluku Islands in 1526 commanded by Sebastian Cabot, who got no further than the west coast of South America before he quit the search and instead explored the interior of the Rio de la Plata. Charles then ordered Hernán Cortés in New Spain (Mexico) to send a rescue mission. Cortés sent a three-ship fleet, but only one of these made it to Tidor, and while it did find the survivors, it could not find favorable winds to get back across the Pacific and was captured by the Portuguese.

Finally, with several armadas lost or unreported, the Spanish sovereign reached the conclusion that the Spice Islands were not worth his effort, and in 1529 decided to make a deal with the Portuguese. In the resulting Treaty of Zaragoza, the Spaniards sold their rights to the Maluku Islands to the Portuguese for 350,000 ducats, and a dividing line between territories was fixed at 17° east of the Maluku Islands. There was an escape clause that allowed the Spanish to have the islands back if they reimbursed the Portuguese, but this never happened. In 1580, the Iberian Union joined the two kingdoms and their Indian Ocean colonies together.

Dutch Conquests & the VOC

For a century, the Portuguese Empire reigned supreme in the Indian Ocean. It was not until 1595 that nine Amsterdam merchants joined together and organized the first Dutch expedition. They chose Cornelis de Houtman to lead it and provided him with four ships. The plan was to follow the traditional Portuguese route around the Cape of Good Hope and then head to Bantam, the main pepper port of Java, and then search for the Spice Islands. The whole affair proved to be a major fiasco, filled with bloody infighting. They never made it to the Spice Islands and brought back very few spices.

A second expedition was sent out in 1598 with six ships, led by Jacob van Neck, with Wybrand van Warwijck and Jacob van Heemskerk, each commanding a ship. Van Neck was a shrewd manager and returned to the Netherlands in July 1599 with four ships loaded with spices. Van Warwijck's ship set off for Ternate, while van Heemskerk's sailed to the Banda Islands. Van Warwijck reached Ternate without incident, was received well, loaded his ship with spices, and headed home, reaching Amsterdam in September 1600. Van Heemskerk got a much cooler reception; however, with lavish gifts and diplomacy, he finally won the trust of the Bandanese and was able to fill his ship with nutmeg. He arrived safely home in late 1600.

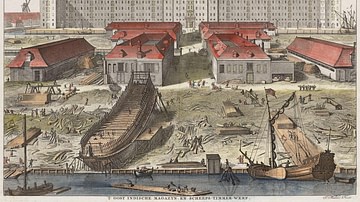

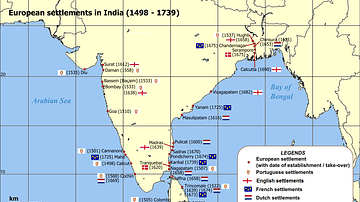

Following van Neck's successful venture, dozens of additional expeditions made the trip to the Spice Islands. To consolidate resources, the government formed the Dutch East India Company (Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie or VOC) in 1602, which was given the power to govern the East and was allowed to run its own shipyards, build forts, keep armies, and make treaties. The first VOC fleet sailed on 18 December 1603, and within a few years, the Company had established a network of hundreds of bases across Asia. By 1605 there were factories on Java, Sumatra, Borneo, the Spice Islands, the Malay Peninsula, and the mainland of India. The whole operation was ruled by a Governor-General who operated essentially as a head of state.

Portuguese Withdrawal

In 1604, the Englishman Henry Middleton was sent to the Indian Ocean with four ships; he arrived at the west Javan port of Bantam on 21 December. Two of the ships were loaded with pepper and sent back home, while Middleton and the remaining two ships traveled to Ambon Island in the Moluccas. Upon arrival, Middleton got permission to trade by convincing the local Portuguese commander that Kings James I of England (r. 1603-1625) and Philip III of Spain (aka Philip II of Portugal, r. 1598-1621) had signed a peace treaty. This was indeed true, but Middleton could not have known this, as the treaty was signed five months after he had gone to sea. Just as they were about to begin loading the ships, an ominous sight appeared on the horizon – a VOC armada. The Dutch had sent a fleet to challenge the Portuguese control of the island, and the English had stumbled into the middle. The English beat a hasty retreat, while the Portuguese suffered a full-scale invasion. Little did Middleton know that he was about to fall into the middle of another Dutch–Portuguese confrontation.

Middleton arrived at Tidore on 27 March just as the Dutch and their allies were about to attack. He was able to convince the Portuguese to allow him to fill his hulls with cloves by staying out of the war. A few days later, the Dutch did successfully take over the Spanish fort on Tidore and began the harassment of the Portuguese on Ternate. The Portuguese finally withdrew from the Maluku Islands in 1663, when it became clear that the cost of maintaining their strongholds exceeded the benefits.

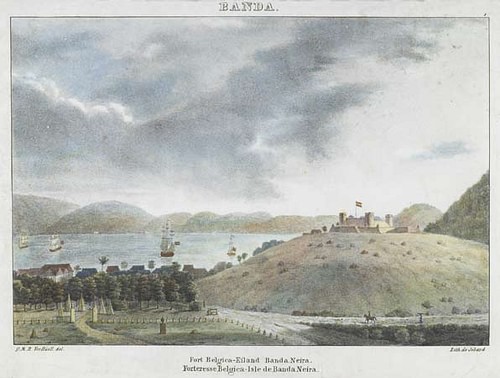

In 1607, Dutch admiral Pieter Willemszoon Verhoeff was sent with a fleet of 13 ships to capture Portuguese Malacca and then build a fort on the Banda Island of Neira. Both missions ended in failure. Verhoeff attacked Malacca but could not take the heavily fortified city. He then headed to the Banda Island of Neira. The leaders of the islands, the Orang Kaya, called a meeting to supposedly negotiate prices and instead ambushed him and two of his officers, decapitated them, and murdered another 46 Dutch soldiers. This ambush would be used repeatedly to justify Dutch oppression and ultimately the near extermination of the Bandanese. One of the men who survived the massacre was Jan Pieterszoon Coen, who carried at that time the modest title of assistant merchant. Upon his return to the Netherlands in 1610, Coen gave the company's directors a report on trade possibilities in Southeast Asia, and he would ultimately become the Director-General.

English-Dutch Confrontations

As Coen and the VOC worked to dominate the spice trade, the English tried desperately to keep a piece of the action for themselves. Coen had begun his reign as VOC director by transferring the VOC headquarters from Bantam to Jakarta and had converted the warehouse there into a fort. In 1618, Sir Thomas Dale was sent from England to break up Coen's growing monopoly, and in a pitched battle, the undermanned fleet of Coen was forced to flee to Ambon for reinforcements. While Coen was away, the sultan of Bantam also decided to enter the fray, forced the English to withdraw, and laid siege to the Dutch fort. When Coen returned in 1619, he was able to push the Bantam forces out of Jakarta, and then he burned the city to the ground. On its ashes, he built the new Dutch city of Batavia, which became the headquarters of the VOC in Southeast Asia.

While the English and Dutch were fighting over Jakarta, another battle was raging between them on the tiny Banda Island of Run. Captain Nathaniel Courthope had reached Run in 1616 and signed a contract with the locals who accepted James I as their sovereign. Under siege by the Dutch, Courthrope held out for 1,540 days before he was killed. Ironically, Coen received word that the Dutch and English leaders back home had reached an agreement in 1620 to cooperate in the East Indies. They were to leave each other's existing trade settlements alone and cooperate against common enemies. A frustrated Coen, however, let the battle over Run play out and named a huge swath of Java as the "Jakarta Kingdom" to keep it out of English hands.

In January 1621, Coen decided to make a full-scale conquest of the Banda Islands. Using Japanese mercenaries, the Dutch took the Island of Lonthor after suffering fierce local resistance that was supported by English-supplied cannon. In response, Coen, and the Dutch massacred thousands of inhabitants, replacing them with slaves from other islands and deporting some 800 inhabitants to Batavia. Only about 1,000 of the original 15,000 survived on the island.

At this point, Coen thought the best future strategy would be to completely colonize the East Indies with Dutch settlers, who would then handle the East India trade. To sell his plan to the VOC directors, he traveled back home in 1623. While there, he was hit with a major scandal, the so-called "Amboyna Massacre" where a group of Englishmen from the small settlement of Cambello in Ambon were taken into custody by the Dutch factors, questioned, tortured, and sentenced to death. They were suspected of working with the locals in a plot to take over the Dutch settlement. Coen was not directly involved, but he was held morally responsible as the leader of the VOC, and he was temporally forbidden to return to Batavia. It was not until 1627 that he was able to go back, traveling incognito, and he died of dysentery there in 1629.

End of the Dutch Spice Monopolies

Throughout the 17th and the early 18th century, the VOC held onto their near-monopoly in the clove trade through their ruthless stranglehold on the Banda Island trade. Nutmeg production in Tidore and Ternate also fell increasingly under their control. In 1652, the leaders of both islands agreed to a spice eradication program (extirpate), where they would allow, for an annual payment, the removal of all clove trees not owned by the VOC. This program was rigidly enforced by the Dutch who made regular expeditions that became notorious for their brutality.

It was the French who finally broke the Dutch clove monopoly in 1770 when Pierre Poivre, a horticulturist and administrator, smuggled out some seedlings from the Spice Islands and planted them on the Isle de France (now Mauritius) and Isle Bourbon (now Réunion). In 1812, an Arab named Harmali bin Saleh transplanted cloves from Réunion to Zanzibar and established plantations which ultimately took over the bulk of world production. Zanzibar dominated the world market until 1964.

During the Napoleonic Wars, the English temporarily seized the Banda Islands. Before the Dutch could regain control, the English uprooted hundreds of nutmeg seedlings and moved them to their own colonies in Ceylon, Singapore, and India, breaking the Dutch monopoly on nutmeg and mace. This ended a Dutch stranglehold on the Indonesian spice industry that had held up for well over 100 years.