The Roman army fought many conflicts throughout its long history, though perhaps none so indelible as the Pyrrhic War from 280 to 275 BCE. This war between Rome and a league of Greek colonies in southern Italy led by the city of Tarentum marks a significant turning point in the Mediterranean world, effectively demonstrating the superiority of Roman political and military policy.

Surprisingly, Tarentum and their hired Greek mercenary general named Pyrrhus (c. 318-272 BCE) initially defeated the Roman army in two out of three major battles, though suffered such heavy casualties that these victories were considered strategic losses. It is from this conflict that the term 'Pyrrhic victory' is derived, denoting a victory that is so damaging to the winning side that it is technically a defeat.

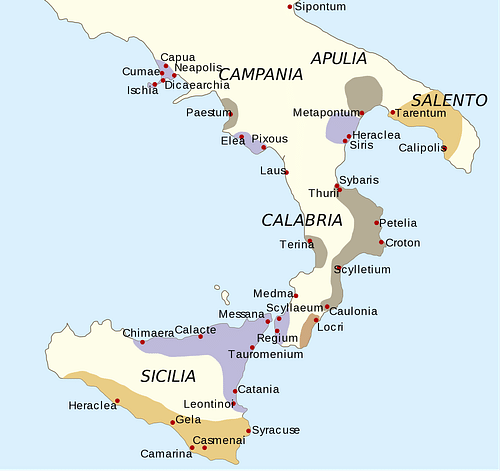

Roman Expansion & Greek Colonization

The Pyrrhic War is important for a variety of reasons, though specifically, it signals a shift away from the established method of Greek warfare to a new approach epitomized by the Roman Republic (509-27 BCE) and its system of allies. Alexander the Great (r. 336-323 BCE) had stormed across most of the known world only 50 years earlier, with Greek (Macedonian) military tactics leading the way. The city of Rome was growing at this time as well though, benefiting from a prime geographic location and drawing upon culturally advanced neighbors like the Etruscan civilization to the north and Greeks to the south.

Roman foreign policy at this time came from a perceived need to defend against foreign threats to their city. The sack of Rome by the Gauls, 390 BCE, left a lasting impression on the Roman psyche and perceptions of their own safety. It encouraged the Romans to embark on a series of defensive wars with their neighbors to create a buffer of security around their territory. One of the consequences of Roman expansion at this time was the acquisition of allied cities that were similar in culture, custom, and language to the Romans. Rome's ability to absorb these communities, culturally and politically, greatly enhanced its military strength, providing manpower to field large armies when threatened.

Roman armies gained valuable experience from 343-290 BCE by fighting three successive conflicts known as the Samnite Wars. These wars helped to consolidate power, allies, and territory across Italy while providing practice to the Roman army by fighting many opponents over varied terrain. In his book Hannibal, the historian Theodore Dodge explains this in more detail in the following passage:

The Samnite wars, more than any other, laid the foundation of the greatness of Rome, solidified the army organization, taught the men to fight in mountains as well as on the level, and to contend with the various difficulties, uncertainties and surprises incident to meeting a succession of new opponents. (105)

By the time the Roman army faced Pyrrhus and his Tarentine allies in 280 BCE, they were a formidable and adaptive fighting force.

In opposition to Rome, the city of Tarentum was a former Greek colony thought to have been founded by the Spartans in the 8th century BCE. Many Greek city-states went through a period of colonial expansion in the 8th and 7th centuries BCE, distributing their cultural and political communities across the Mediterranean. Some Greek cities found that they needed to send off entire segments of their population due to poor soil quality at home making it difficult to feed growing populations. Though nominally independent, these colonies retained cultural and linguistic ties to their mother cities back on mainland Greece. Indeed, these cultural and ethnic ties to the Greek mainland would serve as an avenue for Tarentum when seeking military assistance against aggressive neighbors like Rome.

The Pyrrhic War

The cause of the conflict between Tarentum and Rome probably came from a misunderstanding between the two cities. The historian Appian of Alexandria (c. 95-165 CE) explains that Rome's fleet had wandered into Tarentine waters, resulting in the loss and capture of Roman ships. Livy (c. 59 BCE to 17 CE) also alludes to the mistreatment of Roman ships as a trigger for war in his description here:

When the Tarentines looted a Roman fleet and killed its commander, (282 BCE), the Senate sent them envoys to complain about this injustice, but they were maltreated. Therefore, war was declared (281 BCE). (Perioche, 12)

Whatever the actual circumstances surrounding the causes of the Pyrrhic War, Rome and Tarentum found themselves at odds with one another. Though less militarily inclined than the Romans, the Tarentines did retain connections to mainland Greece where they might find sympathetic leaders to help them. So, Tarentum sought for and found an experienced Greek general willing to come to their aid, as referenced by Mackay in the following passage:

In the past, the Greek communities had at times called upon generals and kings in mainland Greece to help them when in trouble, and in 281 B.C. the Tarentines approached Pyrrhus, the king of Epirus (an area of northwestern Greece). (48)

Pyrrhus of Epirus was sort of a Greek adventurer, general, king, and soldier. Pyrrhus was an interesting character who had marital ties to Ptolemaic Egypt, family ties to Alexander the Great, and had recently reigned as king of all Macedon. As an experienced leader, Pyrrhus was a logical choice for the Tarentines. Not only did the Tarentines seek his assistance but many other Greek city-states in southern Italy said they would contribute aid if he took up the cause against Rome, as they were looking to maintain their own independence. Pyrrhus had recently left the throne of Macedon and was more or less free to undertake a new adventure. Not only would Pyrrhus have access to troops promised by Italian cities but he also possessed his own professional army of experienced Greek mercenaries along with roughly 20 of his own war elephants.

280 BCE marked the beginning of actual fighting in the Pyrrhic War at the Battle of Heraclea in southern Italy. The Romans had raised a large consular army consisting of roughly eight legions (about 40,000 Roman and allied men) led by the consul Publius Valerius Laevinus. Pyrrhus had managed to amass his own large force of roughly: 26,000 heavy infantry, 2,000 archers, 500 slingers, 5,000 cavalry, and his 20 war elephants. Roman warfare at this time used a formation that spread the width of their lines fairly wide in comparison to the Greek phalanx, which worked more effectively in a narrower, more confined space.

The significance of how the two sides lined up for battle was that the wider Roman line could threaten to envelop around the sides of a narrower enemy line facing it, which it could then attack on their flanks. The Romans further divided their soldiers into smaller groups (maniples) of about 120 men segmented by age and experience along three separate lines in a checkerboard pattern. Roman maniples were much more versatile in battle than the standard Hellenistic phalanx, which performed well when facing forward but had trouble turning and maneuvering to address enemies from the sides or rear.

When the two forces clashed at Heraclea, both experienced mounting casualties from repeated charges against each other's formations. Luckily for Pyrrhus, the Roman army had not previously encountered war elephants, and when he brought them up toward the end of the day, they terrified the Roman horses who scattered. When the Roman cavalry mounts took flight, it exposed the flank of their infantry, which would turn the tide and clear the field. Regardless, casualties were heavy on both sides as Plutarch (c. 46-119 CE) explains here:

Dionysius states that nearly fifteen thousand of the Romans fell…on the side of Pyrrhus, thirteen thousand fell…These, however, were his best troops; and besides, Pyrrhus lost the friends and generals whom he always used and trusted most. (Parallel Lives, 17.4.)

Heraclea was significant because, although Pyrrhus technically won the battle, he lost an important part of his army along with his most experienced officers, who were nearly impossible to replace. It is estimated that Pyrrhus may have lost 15% of his entire force in this single engagement. The Romans, who also suffered casualties, could draw upon greater reserves of manpower and resources from allies to rebuild their strength. Though victory at Heraclea permitted Pyrrhus to receive some reinforcements from nearby cities, they could not adequately replace his experienced officers and battle-hardened soldiers brought from Epirus, limiting the effectiveness of his fighting force.

Greek vs. Roman Tactics

After Heraclea, differences in Roman vs. Greek custom toward warfare became apparent, and Pyrrhus would demonstrate a poor understanding of this. The Greek world fought military conflicts differently than the Romans, and naturally, Pyrrhus approached the Romans as a Greek victor seeking terms for Roman surrender because he had won the battle. Romans did not give up after losing a single battle though, and they were not inclined to treat for terms, especially because they had all the necessary tools in place to raise another army and continue fighting.

A truce declined, both sides prepared for the next battle over the coming months, which took place at Asculum in 279 BCE, roughly midway between Tarentum and Rome. Both sides had gathered large forces again, though the Romans employed anti-elephant wagons with hooks and burning torches attached in an adjustment to their battle lines this time. Once again, Pyrrhus' elephants turned the tide of battle despite the efforts of the Romans to disable them. Both sides fought valiantly almost to a stalemate upon departing the field. Plutarch notes casualties at roughly 6,000 Romans to Pyrrhus' 3,505. Though Asculum may technically be considered another Greek victory, Pyrrhus could not adequately replace his men as his forces were being slowly whittled away. Plutarch recounts Pyrrhus' situation after Asculum in the following passage:

…we are told that Pyrrhus said to one who was congratulating him on his victory, "If we are victorious in one more battle with the Romans, we shall be utterly ruined." For he had lost a great part of the forces with which he came, and all his friends and generals except a few; moreover, he had no others whom he could summon from home, and he saw that his allies in Italy were becoming indifferent, while the army of the Romans, as if from a fountain gushing forth indoors, was easily and speedily filled up again, and they did not lose courage in defeat, nay, their wrath gave them all the more vigour [sic] and determination for the war. (21.9-10.)

Pyrrhus simply did not have the same logistic capacity that the Romans did for replacing men. Roman access to resources and manpower was a direct result of the city's efforts to incorporate allied communities as Mackay explains: "The Romans clearly had a flair for incorporating such communities into their political and military system, through both direct absorption and the making of treaties" (49). Essentially, the Romans' resolve, system of allies, and political unity allowed them to continue a war effort in which they were technically losing, presenting Pyrrhus with a situation he was ill-equipped to deal with.

Realizing that he would be unable to fully defeat the Romans after Asculum, Pyrrhus decided to embark on a new adventure to Sicily in 278 BCE. He was long said to have been eyeing Sicily, Sardinia and Carthage itself, so he jumped at an invitation to do so, hoping to face weaker opponents than the Romans. Plutarch explains this episode in the following passage:

For at one and the same time there came to him from Sicily men who offered to put into his hands the cities of Agrigentum, Syracuse, and Leontini, and begged him to help them to drive out the Carthaginians and rid the island of its tyrants…Sicily appeared to offer opportunities for greater achievements…The Tarentines were much displeased at this, and demanded that he either apply himself to the task for which he had come, namely to help them in their war with Rome, or else abandon their territory and leave them their city as he had found it. (The Life of Pyrrhus, 25)

Though initially successful, Pyrrhus' adventure to Sicily yielded little long-term benefit, and he found himself back in Italy just two years later to face a fully rebuilt and retrained Roman army.

In 275 BCE, the final battle of the Pyrrhic War occurred at Beneventum. Pyrrhus attempted a night march through uncertain terrain to surprise one of the Roman consular armies under Manius Curius. His troops became lost, disorganized, and weakened during this difficult maneuver, leaving Pyrrhus at a disadvantage when battle commenced at daybreak. The Romans had also adapted to fighting against Pyrrhus' elephants, who had helped so much in earlier engagements. Elephants were unpredictable war machines at the best of times and were known to periodically spook, stampeding into their own troops as they fled, disrupting battle lines, and this occurred at Beneventum.

Though the battle was close, the Roman army had made necessary adjustments and appear to have won the day. After the battle, Pyrrhus sought refuge in Tarentum and soon thereafter left Italy for good. Roughly three years later in 272 BCE, Pyrrhus was killed in a minor scuffle in Greece, signaling an unremarkable end to a very remarkable life.

Conclusion

The Roman Republic would face many opponents throughout its long history, and in many circumstances, they lost battles. Romans actually lost battles all the time, but what made the Roman army so tenacious was not their invincibility, but their logistic capacity for rebuilding depleted forces. Furthermore, new Roman armies had the benefit of learning from prior mistakes which they could implement in future battles, increasing their effectiveness as wars dragged on. The political skill and unity demonstrated through the Roman network of allied cities directly contributed to their success, especially during the middle years of the Republic. This rather unique ability to access manpower for its armies gave Rome the opportunity to continue fighting and grinding its opponents down.

In contrast, the established Greek method of warfare where opponents sought treaties after one or a few significant engagements was entirely different from the Roman attitude toward war and arguably antiquated in comparison. The aftermath of Heraclea and Asculum during the Pyrrhic War are poignant examples of how the Greek and Roman systems of warfare differed. Though both sides possessed valiant soldiers, what turned the tide in this war was the political and logistic ability of the Roman military to raise new armies that could adapt to changing circumstances. Though Pyrrhus was able to achieve a few short-term victories, he lost too many valuable and irreplaceable men as his army was slowly whittled away. The Pyrrhic War marks a significant turning point for the balance of power in the Mediterranean world, away from the Greek and toward the Roman style of efficient and total war.