No other Roman emperor travelled as much as Hadrian (r. 117-138 CE). The 'restless' emperor spent more time travelling than in Rome, devoting half of his 21-year reign to the inspection of the provinces. His travels provided him with the political means of unifying the Roman Empire, but he may also have been personally motivated by his insatiable curiosity, philhellenism, and love of travel.

Memories of Hadrian have been inextricably linked with his long administrative journeys throughout the empire. The author of the Historia Augusta tells us that the emperor was "so fond of travel, that he wished to inform himself in person about all that he had read concerning all parts of the world" (HA Hadr. 17.8). The Christian writer Tertullian (155-210 CE) speaks of Hadrian as "omnium curiositatum explorator" (Apology 5.7), "an explorer of all curiosities". Cassius Dio (c. 164 to c. 229/235 CE) writes: "He personally viewed and investigated absolutely everything" (69.9.2).

However, Hadrian's travels were not only the result of a hedonistic wanderlust. He was a capable administrator and a competent military commander. His voyages were part of a global policy aimed at inspecting western and, in particular, eastern provinces, and at supporting local communities through donations. If Hadrian is often portrayed as a passionate intellectual with an insatiable curiosity and thirst for discovery, he was also a man determined to remind his provinces who was in charge.

Emperor on the Move

Hadrian's reign was marked by a series of long journeys, during which he visited virtually every province of his empire. Contemporary scholarship has paid much attention to determining exactly where Hadrian went, trying to reconstruct the itineraries of his three major journeys which are now possible through the evidence provided by ancient writers, inscriptions, coins, and papyri.

Hadrian's first extended trip is often forgotten since it occurred at the very beginning of his reign, between his accession to the throne in August 117 CE and his arrival in Rome in July 118 CE. Hadrian spent some time in the Syrian capital settling a new military and diplomatic order, which involved the withdrawal of troops from Trajan's (r. 98-117 CE) newly conquered provinces beyond the Euphrates and returning Mesopotamia and Armenia to their client kings. At the time of Trajan's death, the extent of the Roman Empire was at its greatest. The new emperor was concerned with securing the frontiers in the East where the conquests were proving difficult to hold and defend.

Hadrian travelled through one province after another, visiting the various regions and cities and inspecting all the garrisons and forts. Some of these he removed to more desirable places, some he abolished, and he also established some new ones. (Cassius Dio 69.9.1)

In the autumn, he left Antioch but did not directly travel back to Rome. Instead, he set out for the Danubian frontier to negotiate peace with the king of the Roxolani, a Sarmatian tribe who were mounting an offensive and attacking the limes (frontier line). According to the Historia Augusta, he returned to Rome via Illyricum, and in a rare instance, it is possible to follow his steps for a few days thanks to epigraphical sources. From 12 to 18 October, Hadrian was on the via Tauri between Cilicia and Cappadocia; from late October to 11 November, he followed the road from Ancyra (modern-day Ankara) to Juliopolis in Bithynia.

Between 121 and 125 CE, Hadrian travelled to Roman Gaul and through the northwestern provinces in Germany and Roman Britain, where he spent a few months erecting new borders for the empire. In 123 CE, he was in northern Spain in Tarraco (modern-day Tarragona), and then he travelled east to the Syrian capital to respond to news of danger and make a peaceful settlement with the Parthian king. In 123-124 CE, Hadrian moved through various parts of Asia Minor. He then returned to Athens where he financed an ambitious building programme, visited Delphi, and was initiated into the Eleusinian Mysteries at Eleusis. A few years later in 128 CE, the emperor sailed for the African provinces and then headed east again. He returned to Greece and moved on to the eastern frontier with a trip to Palmyra. In 130 CE, he travelled through Judea and Arabia on his way to Egypt. Then came a trip to Judea in 132 CE to deal with the Bar-Kochba Revolt.

Hadrian travelled because of his natural curiosity and a strong fondness for the East, but his long absences from Rome were part of a global policy aimed at unifying and stabilising the vast empire as well as consolidating his imperial authority. By inspecting the provinces, supporting local communities, and creating a direct link between the emperor and his subjects, Hadrian showed that he was a man of peace and that he could guarantee prosperity.

The Challenges of Travel

Travel was not unusual in Roman times and was mainly connected to either military or commercial activities. Before Hadrian, soldier-emperors such as Augustus (r. 27 BCE to 14 CE) and Trajan visited their empire for further conquests. When Hadrian came into power, he had already travelled to a large part of the Roman world. The early careers of many senators involved military service outside Italy and usually the governing of a province. Hadrian joined the legion as a military tribune at the age of 19 and was sent to the garrison of the legions of Pannonia. He went on to assume two more tribunates, in Oescus in modern-day Bulgaria and then in Mogontiacum (Mainz, Germany).

Later, Hadrian served with the legions of the Dacian Wars for most of the military campaigns led by Trajan. In 106-108 CE, he returned to Pannonia as provincial governor. In 112 CE, he made his way to Athens and spent some time there as eponymous archon, the highest magistrate in Athens. At the end of 113 CE, Hadrian followed Trajan eastward on a fateful expedition against Parthia. He became governor of Syria, establishing his headquarters in Antioch, where he was to take power after Trajan's death in Cilicia (southern Turkey) in August 117 CE.

These trips were made possible thanks to the efficient system of communication and the sophisticated transport network that consisted of road, maritime, and fluvial routes. The vehiculatio (sometimes also called cursus publicus), the imperial transport system founded by Augustus, also played a vital role in securing state communication and travel along the major thoroughfares of the empire. Information, goods, and services could be transported along the main roads, and a system of stopping places at regular intervals (mansiones) developed during the Roman imperial period. Another system of way stations serviced vehicles and animals: the mutationes. They dotted Roman roads every 12 miles or so and provided overnight accommodation, stables, and refreshments. However, the maintenance of this imperial posting service was particularly onerous and a burden that fell on local communities. Concerned about the efficient operation of the vehiculatio, Hadrian reorganised the system and assumed full imperial control, removing provincial responsibilities.

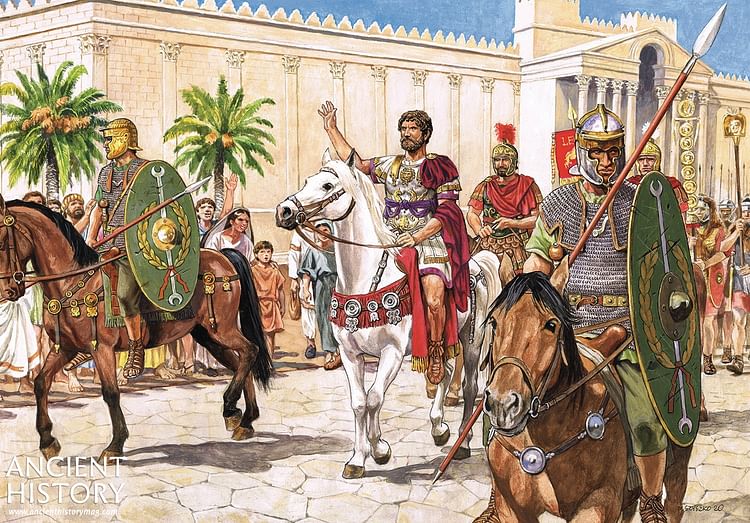

Hadrian made multiple stops along his route, and the only extant itinerary of his journeys between Cilicia and Cappadocia reveals that he travelled at a reasonable pace of approximately 37 kilometres (23 mi) per day, compared to the usual speed of the vehiculatio of 45 kilometres (28 mi) on average. Cassius Dio (69.9.3) mentions that Hadrian "walked or rode on horseback on all occasions, never once at this period setting foot in either a chariot or a four wheeled vehicle" and that he always walked around bareheaded, even in extreme weather. Aurelius Victor (c. 320 to c. 390 CE) adds that "he made a circuit of all the provinces on foot, outstripping the accompanying retinue" (Epitome de Caesaribus 14.4-5).

He [Hadrian] journeyed not only into frosty lands, but also into other lands in southern locations, in order to safeguard the provinces which, lying across the rivers of the Euphrates and the Danube, Trajan had annexed to the Roman Empire. (Fronto, Principia Historiae 11)

Considerable preparation and mastery of logistics would be vital to ensure the success of Hadrian's visits to the provinces. The movement of the imperial court involved considerable logistical support. Hadrian's travelling entourage may have included as many as 5,000 individuals, including his wife and her staff, imperial secretaries, personal friends and advisors, officials, servants, guards, architects, and craftsmen, but also men and women of letters. It was the Roman government on the move, a colossal travelling court that put a strain on the resources of the area through which it passed.

Documentary sources reveal that extensive preparations were required many months in advance. A papyrus attests that before Hadrian's arrival in Egypt in 130 CE, the city of Oxyrhynchus was stockpiling a generous supply of food, including 372 suckling pigs and 2,000 sheep, as well as dates, barley, olives, and olive oil. Hadrian was followed by a large number of petitioners hoping to present to him their plight. One famous anecdote is recounted by Cassius Dio: a woman approached Hadrian with a request. At first, he told her that he was too busy. She replied, "Then stop being an emperor!" He turned around and granted her a hearing. Dio also tells us how he liked to travel as an ordinary citizen and live like a soldier, getting personally involved in the training of his men.

To the Western Provinces (121-123 CE)

Hadrian spent less than three years in Rome before he embarked on an ambitious tour of the western provinces. He headed north to the Germanic regions, passing through Gaul. Hadrian probably landed at Massilia (Marseille) and sailed up the Rhône river to Lugdunum (Lyon), before continuing to Mogontiacum, the capital of Germania Superior, where he may have wintered. Hadrian's motive in going to Germany was to inspect the military installations between the Rhine and the Danube and erect a new border for the empire (the so-called Upper Germanic-Rhaetian Limes). The limit of the empire was to be marked by a continuous wooden palisade running from the Main to the River Neckar. Hadrian visited the fixed quarters of the legions where he lived with the troops, sharing their basic military diet and eating, like a Roman legionary, in the open. His concern was also on keeping the soldiers fit and active, and he insisted that rigorous training programmes be introduced to reinvigorate discipline among the soldiers. During his residence in Germany, Hadrian also visited the provinces of Raetia and Noricum.

Hadrian and his entourage then went to Britain to secure the frontier system across northern England. The emperor responded to an uprising of the Celtic Brigantes that had broken out earlier at the beginning of his reign, inflicting considerable casualties on the army. The details of Hadrian's movements within the province are tantalisingly sketchy as we have no record of where he went. The only reference in ancient literature to Hadrian's Wall and his actions while in Britain comes from the Historia Augusta. The author tells us that Hadrian "put many things to right and was the first to build a wall 80 miles long from sea to sea to separate the barbarians from the Romans" (HA Hadr. 11.2). The Wall crossed northern Britain from Wallsend on the River Tyne in the east to Bowness-on-Solway in the west, with further defensive installations along the Cumberland coast.

Hadrian's Wall was constructed north of the existing line of forts and other military installations, with guarded gates every 1.5 km (1 mi) and observation towers every 500 metres (1,640 ft). Ultimately, 14 forts were added to the Wall, each holding between 500 and 1,000 auxiliary troops, followed by an earthwork known as the Vallum to the south. However, this great fortification was not only intended to act as a fence against a northern enemy. It also allowed the efficient control of any traffic of people and goods. As in Germany, Hadrian probably inspected the legions of Britain and insisted on regular manoeuvres to maintain discipline.

Returning to the Continent in late 122 CE, Hadrian travelled through Gaul to reach Spain. He spent the winter of 122/3 CE in Tarraco (Tarragona) and took a trip to the sole Spanish legionary base at Legio (León). While there, news reached him that the Parthian king threatened war, and he sailed east.

First Journey to the East (123-125 CE)

By June 123 CE, Hadrian was back with his retinue in Antioch, where his rule had begun. The Historia Augusta tells us that he held a summit meeting with the Parthian king on the Euphrates. Again, Hadrian seems to have settled the dispute by diplomacy. From Antioch, he went on to inspect the Cappadocian frontier, then proceeded westwards along the Pontic shore through Galatia into Bithynia. It was at this time that Hadrian met Antinous (l. c. 110-130 CE), who became his inseparable companion for the next seven years. He spent 123/4 CE in Nicomedia, and in spring he went on to visit Nicaea and then a series of cities in the province of Asia, including Cyzicus, Ilium, Pergamon, Smyrna, and Ephesus. He also went hunting in Mysia and founded a new town, Hadrianutherae ("Hadrian's hunt"), on the spot where he had a successful bear-hunt.

In the autumn of 124 CE, Hadrian ended his eastern journeys by spending the winter of 124/5 CE in Athens. From Athens Hadrian embarked on a brief tour of the Peloponnese, visiting Argos and Sparta among other cities. He then travelled to Delphi and consulted the oracle. On his return to Rome, Hadrian sailed to Sicily, where he climbed to the top of Mount Etna to witness the sunrise.

Hadrian in Northern Africa (128 CE)

Still concerned about military matters, Hadrian embarked on a brief voyage to North Africa in the late spring of 128 CE. His arrival in Carthage coincided with the first rains after five years of drought. The city was temporarily renamed Hadrianopolis, and a new aqueduct was built on Hadrian's orders. He then made his way inland to visit the legionary fortress at Lambaesis in Numidia (modern-day Algeria). During his six-day stay, the legion put on a display of military exercises. Afterwards, on 1 July, Hadrian gave a speech before the assembled soldiers to praise them for their abilities. Some excerpts of his speech have survived on a fragmented inscription. On 7 July, Hadrian inspected an auxiliary cohort at Zaraï; from there he proceeded to an unknown destination to visit another cohort, then sailed back to Rome.

Second Visit to the East (128-134 CE)

Military matters were not Hadrian's only concern, and his final excursion saw him enjoying a tour of the empire, very much like a tourist, while also inspecting and fostering his relations with the local populations. This last trip to the East was to take six years. The emperor sailed for Athens in late 128 CE and spent the winter in Greece. Once again he was accompanied by his wife, Sabina, and a whole group of companions. Next spring, he sailed from Eleusis to Ephesus and travelled widely through Asia Minor. Many Greek cities recorded benefactions from Hadrian's visits in the form of buildings or even foundations. After spending the winter 129/130 CE in Antioch, Hadrian visited Palmyra in the Syrian desert.

From Syria, Hadrian went to Egypt, passing through Phoenicia and Judea. He first visited the tomb of Pompey the Great (l. 106-48 BCE) and then moved on to Alexandria. Here, Hadrian restored the Temple of Serapis and visited the Mouseion. Next, the party went on a cruise up the Nile. Along the way, he probably visited the pyramids of Giza, but on 24 October, a horrible accident occurred: Antinous drowned in the Nile. Within a week, Hadrian decided to build a new city where his lover had died, Antinoöpolis, and the youth was declared a god. Despite the tragedy, the touring party continued down the Nile and visited the colossal statues of Pharaoh Amenhotep III (c. 1386-1353 BCE), the so-called 'singing' Colossi of Memnon.

After spending the winter of 130/1 CE in Alexandria, Hadrian returned to Athens, where he contributed to further benefactions and inaugurated the Temple of Olympian Zeus. Then, in late spring or early summer 132 CE, news arrived of a revolt in Judea, and Hadrian returned to the province to take charge. The emperor's final return to Rome is certified by epigraphy on 5 May 134 CE. Hadrian then fell seriously ill and retired to the seaside resort of Baiae on the Bay of Naples, where he died on 10 July 138 CE.

Publius Annius Florus, a Roman historian and poet who befriended Hadrian, once wrote a short poem mocking Hadrian's travels.

I don't want to be a Caesar,

Stroll about the Britons,

Lurk about among the [...]

And about the Scythian winters. (HA Hadr. 16.3)

Hadrian's response showed his sense of humour:

I don't want to be a Florus,

Stroll about among the taverns,

Lurk about among the cool shops

And endure the round fat insects. (HA Hadr. 16.4)

In Hadrian's mind, travel and effective governance were closely tied. He had realised that the empire's survival depended on Rome and on the loyalty of the provinces. This visionary approach led to a relatively peaceful and prosperous era, which many see as the golden age of the Roman Empire.

This article was originally printed in Issue 31 of Ancient History Magazine.