The Battle of Edgehill in Warwickshire on 23 October 1642 was an early engagement in the English Civil Wars (1642-1651) and the first major battle of that conflict. The Royalist forces loyal to Charles I of England (r. 1625-1649) met an army sent by Parliament near Kineton; fought over a single afternoon and evening, the result was indecisive.

An early Royalist cavalry charge led by Prince Rupert (1619-1682) had been highly successful, but their departure from the field in pursuit of the enemy left the Royalist infantry dangerously exposed. Heavy fighting led to total casualties of around 1,500 and a draw, which indicated that the Civil War was likely to become a long and protracted one.

Civil War

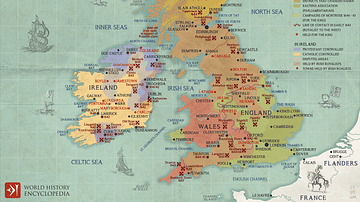

King Charles I considered himself an absolute monarch with absolute power and a divine right to rule, but his unwillingness to compromise with Parliament, particularly over money and religious reforms, led to a civil war from 1642 to 1651. Fought between the 'Roundheads' (Parliamentarians) and 'Cavaliers' (Royalists) in over 600 battles and sieges, the war was a long and bloody conflict. The northern and western parts of England largely remained loyal to the monarchy, but the southeast, including London, was controlled by Parliament.

In July 1642, the same month that Charles unsuccessfully besieged Hull, Parliament agreed to raise an army to face those forces being assembled by the king. The Parliamentarian army was to have 10,000 men commanded by Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex. Its real purpose was to meet the military threat from the Royalists, but officially, at least, it had a more general directive:

[To secure] the safety of the King's person, defence of both Houses of Parliament, and of those who have obeyed their orders and commands, and preserving of the true religion, the laws, liberty and peace of the kingdom.

(Bennet, 30).

This directive does encapsulate the general feeling at the time that Charles was not to be deposed but, rather, persuaded – by force, if necessary – to stop following policies the Parliamentarians believed originated from his evil counsellors. Nevertheless, the situation turned towards an all-out war when Charles made his intent clear and raised the royal colours at Nottingham on 22 August 1642.

There were several minor skirmishes and incidents as the Civil War stuttered to begin proper. A Royalist army won a skirmish at Powick Bridge on 23 September, but another had failed to take control of Warwick Castle. Parliament already controlled the Royal Navy, a significant impediment to Charles receiving reinforcements from the Continent and Ireland. Prince Rupert, Charles' nephew and commander of the Royal cavalry, did take the armoury of Leicester. Troops were mustered at various key locations in England on both sides while final talks were conducted to thrash out a peaceful settlement, likely for both sides a tactic merely to gain time to organise their forces. The war gods had already cast the die, and the first major land battle was at Edgehill (near Kineton, Warwickshire) on 23 October, as it turned out, one of the most significant of the entire war.

Armies & Deployment

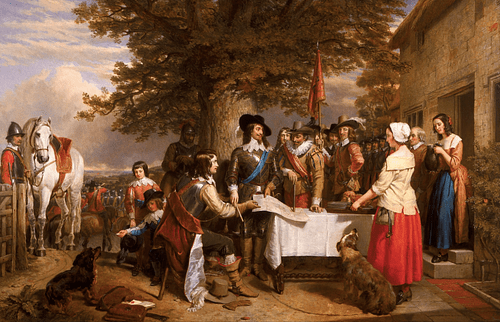

King Charles and the Earl of Essex commanded their respective armies in person. The king had wisely taken the high ground on Edgehilll, a ridge 3.2 kilometres (2 mi) long on the evening of Saturday 22 October. On the next morning, his army prepared to march down to face-off with the Parliamentarian army which had assembled near Kineton to the west. The king gave his troops a final pep talk, as described by the Royalist cavalry officer Sir Richard Bulstrode:

The King was that day in a black velvet coat lined with ermine, and a steel cap covered with velvet. He rode to every brigade of horse, and to all the tertia's of foot, to encourage them to their duty, being accompanied by the great officers of the army; his majesty spoke to them with great courage and cheerfulness, which caused huzza's thro' the whole army. (Hunt, 104)

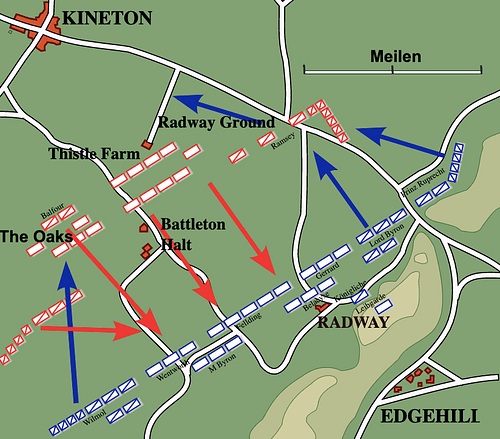

The Royalists had their cavalry on the flanks, while in the centre were mixed divisions of pikemen and musketeers. Historians continue to debate whether there were five or nine infantry brigades but do agree they were organised in squares like a checkerboard, which allowed the rear line to fill the gaps ahead if and when required. Pikemen were infantry armed with pikes: ash poles some 5.5 metres (18 ft) in length and topped by a metal spike. Musketeers fired matchlock muskets, typically operating in ranks, which fired more effective volleys than single fire. The dragoons, a sort of mixed infantry-cavalry, were positioned on both flanks. The Parliamentarian army was similarly organised and more or less equal in size to the 13-14,000 men led by the king. The former likely had more infantry, while the king had numerical superiority in cavalry. The Parliamentary infantry was likely organised into three divisions – two at the front and one at the rear – composed of 12 regiments in all. Both sides had artillery units, which opened the battle at 3 pm. Cannons were fired into the enemy for around one hour to soften them up and disrupt their formation, particularly of the tightly-packed pikemen. There were also several skirmishes between companies of dragoons.

Rupert's Cavalry Charge

Rupert's cavalry attacked from the right wing, at first with great success thanks to their tight formation, angled attack, and the riders all firing their pistols. A portion of the Parliamentary cavalry withdrew at the onslaught while others were less effective than they should have been, perhaps because they had fired their firearms before the enemy was within range. On the other flank, the Royalist cavalry led by Lord Wilmot also made gains. However, pursuing the retreating enemy horse, the departure of Rupert's cavalry from the field left the Royalist infantry centre dangerously exposed. There was no or, at least, only a very small royalist cavalry reserve which, in normal circumstances, would have protected the artillery and provided the infantry cover from an attack by the enemy's cavalry reserve. As the military historian M. Wanklyn notes, "This failure to retain a true reserve almost certainly lost Charles the chance of a decisive victory" (44). The Royalist army had been deployed in an entirely attacking arrangement, but this left no room for meeting a counterattack.

The Infantry Clash

The Royalist infantry had marched down the 90-metre (300 ft) high rise to meet the Parliamentarian army in a large open area then known as the Vale of the Red Horse. This was the moment the Royalist infantry commander Jacob Astley said his famous prayer: "O Lord! Thou knowest, how busy I must be this day; if I forget thee, do not thou forget me. March on boys!" (Hunt, 105). Essex's infantry and some cavalry which had been left in reserve charged at the Royalists. A unit led by William Balfour overwhelmed a battery of Royalist artillery, and even the Royal standard was briefly captured before two men disguising themselves as Parliamentarians, wearing the yellow sash field sign, grabbed it back again. Rupert's cavalry was by now looting Essex's baggage train far away at Kineton, but the Royal infantry held their own until around 5 pm, and the cavalry finally returned from its sortie. The fighting at close quarters was intense, but no significant advantage was gained by either side when nightfall and a lack of ammunition brought the fighting to a close.

Stalemate: The War Goes On

On 24 October, after a bitterly cold night in the field, which claimed yet more lives, Essex withdrew to Warwick Castle. Around 1,500 had been killed in the battle. Charles could have now moved on towards London, his original target, but his army delayed by capturing Banbury and establishing a garrison at Oxford. This delay gave the Parliamentarians time to assemble outside the capital, Essex joining forces with the London Trained Bands. Put off by the 20,000 men arranged against him, in November Charles withdrew from Turnham Green to Reading and then Oxford, which became the Royalist capital. It was a typical game of cat and mouse that typified much of the encounters yet to come. Unlike everyone had hoped, the war was not at all going to be all over by Christmas; this was going to be a long and bitter conflict.