Enheduanna (2285-2250 BCE) is the world's first author and was the daughter (either literally or figuratively) of the great empire-builder Sargon of Akkad (2334-2279 BCE). Her name translates from the Akkadian as `high priestess of An', the god of the sky or heaven, though the name `An' could also refer to the moon god Nanna (also known as Su'en/Sin) as in the translation, `en-priestess, wife of the god Nanna' or to the Queen of Heaven, Inanna, a goddes Enheduanna helped `create'. All these translations are distinct possibilities in that merging the gods of different cultures was perhaps Enheduanna's greatest talent. According to the scholar Paul Kriwaczek:

While the language of Sargon's court in the northern part of the alluvial plain was Semitic, and his daughter surely would have had a Semitic birth name, on moving to Ur, the very heartland of Sumerian culture, she took a Sumerian official title: Enheduanna - `En' (Chief Priest or Priestess); `hedu' (ornament); `Ana' (of heaven). (120)

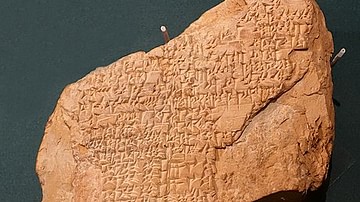

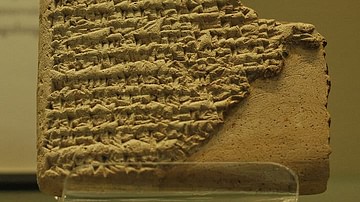

She is best known for her works, Inninsagurra, Ninmesarra, and Inninmehusa, all three hymns to the goddess Inanna which, according to the Enheduanna scholar Betty de Shong Meador, “effectively defined a new heirarchy of the gods (51). These hymns, translated as `The Great Hearted Mistress', `The Exaltation of Inanna' and `Goddess of the Fearsome Powers', gave to the people of Sargon's empire a personal and meaningful vision of the gods who steered their lives.

Early Life and Rise to Power

Nothing is known of Enheduanna's life prior to her appointment as Chief Priestess of the temple complex at Ur. Scholar Jeremy Black, among others, even questions whether the hymns attributed to her are actually her work or those of a scribe working under her and writing in her name. It is also unclear whether she was Sargon's biological daughter or whether the references to her relationship with Sargon are to be understood figuratively. She could have been his "daughter" in the sense of a trusted and devoted member of Sargon's extended "family" of bureaucrats who helped maintain his empire.

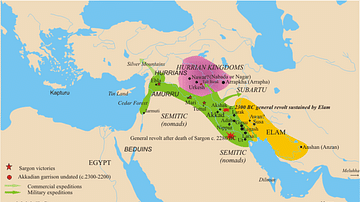

Sargon of Akkad (also known as Sargon the Great) reigned for fifty-six years over the Akkadian Empire which he founded and held together through military might and skillful diplomacy. Among his many shrewd diplomatic decisions was his attempt to identify the Sumerian gods of the people he had conquered with his own Akkadian gods, those of the conqueror. Understanding the power of religion to unify or divide, Sargon appointed only very trusted associates and family members to the most important positions in the Sumerian temples where they could then gently influence those who worshipped there.

Among these religious appointees, the most successful was Enheduanna who, through her hymns and poetry, was able to identify the different gods of the differing cultures with one another so strongly that the gentler and more localized Sumerian goddess Inanna came to be identified with the much more violent, volatile and universal Akkadian goddess Ishtar, the Queen of Heaven.

Enheduanna and Innana

Inanna was originally a local Sumerian deity associated with fertility and vegetation who, later, was elevated to the position of Queen of Heaven. The Sumerian poem, The Descent of Innana, which some have claimed Enheduanna had a hand in translating, has the Sumerian goddess descend from the heavens to the underworld to visit her recently-widowed sister Ereshkigal.

An important, and often-overlooked, aspect of this work is that it relies on an audience's acquaintance with an episode from The Epic of Gilgamesh in which Ishtar indirectly causes the death of Gugalanna - the Bull of Heaven - who was Ereshkigal's husband. If one knows that story, then Inanna's poor reception at Ereshkigal's court makes perfect sense. It would also be in line with Enheduanna's agenda of melding diverse cultural and religious beliefs to use the legend of Ishtar's fury over rejection by Gilgamesh into the back story of the poem. The claim that she translated the poem, however, is entirely speculative - the extant versions of The Descent of Inanna all come from centuries after Enheduanna's life - but the identification of Inanna with Ishtar is suggestive of a poet attempting to unify different religious visions.

That the poem presents Inanna-as-Ishtar, Queen of Heaven, rather than a localized deity, reveals the underlying shift in importance from Inanna pre-Enheduanna to Inanna after her priestess had influenced the understanding of this deity. Even if she did not translate the poem, her own poetic works influenced later translators. So closely were Inanna and Ishtar interwoven that the poem was famously known as The Descent of Ishtar until the 20th century when archaeological finds unearthed the works in praise of the Sumerian goddess Inanna.

Empire Builder

Whether Enheduanna actually did translate The Descent of Inanna is unimportant in that her work in shaping the understanding of the goddess (and, by extension, the other gods) would have influenced whoever did bring the Sumerian story of Inanna into Akkadian. In this way, Sargon melded the culture of the conquered with his own, crafting from the two a strong, united empire.

According to historian D. Brendan Nagle, “So successful was Enheduanna in smoothing over the differences between north and south that the king of Sumer continued to appoint his daughter to the position of high priestess of Ur and Uruk long after Sargon's dynasty disappeared” ( 9). Paul Kriwaczek also comments on Enheduanna's successful comportment as high priestess when he writes:

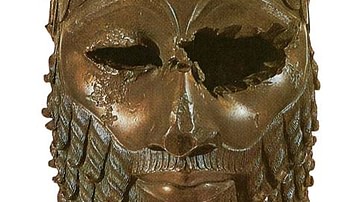

She moved into the Giparu at Ur, an extensive and labyrinthine religious complex, containing temple, quarters for the clergy, dining and kitchen and bathroom areas, as well as a cemetery where En-priestesses were buried. Records suggest that offerings continued to be made to these dead preiestesses. That one of the most striking artefacts, physical proof of Enheduanna's existence, was found in a layer dateable to many centuries after her lifetime, makes it likely that she in particular was remembered and honoured long after the fall of the dynasty that had appointed her to the management of the temple. (120)

Enheduanna's importance is increasingly appreciated in modern times for the richness and beauty of her poetry, often employing sexual imagery as a means of expressing love and devotion. Kriwaczek notes:

Her compositions, though only rediscovered in moern times, remained models of petitionary prayer for [nearly 2,000 years]. Through the Babylonians, they influenced and inspired the prayers and psalms of the Hebrew Bible and the Homeric hymns of Greece. (121)

These later works, however (particularly the psalms) are far more repressed concerning sexuality, which was far more freely discussed and represented in Mesopotamian art and literature. At the same time, Enheduanna does not hold back in displaying the awesome power and might of her goddess who has no tolerance for disobedience, ingratitude, or rebellion. In her poem, The Exaltation of Inanna, Enheduanna makes clear the fate in store for those who displease the goddess:

Let it be known that you are lofty as the heavens!

Let it be known that you are broad as the earth!

Let it be known that you destroy the rebel lands!

Let it be known that you roar at the foreign lands!

Let it be known that you crush heads!

Let it be known that you devour corpses like a dog!

Let it be known that your gaze is terrible! (lines 123-129)

Inanna's gentle, nurturing aspects are thus balanced with her war-like, vengeful attributes and those who might consider rebelling against Sargon's rule - or refusing to comply with the edicts of his High Priestess - were clearly warned of the retribution awaiting them. The Exaltation of Inanna, in fact, addresses this very problem specifically in citing a Sumerian rebel named Lugal-Ane who managed to usurp her position and drive her into exile. At the end of the poem, it is clear that Lugal-Ane has been dealt with by Inanna and Enheduanna has been restored to her rightful position.

Conclusion

In addition to her longer works, she wrote forty-two shorter poems on a wide range of themes from personal frustration and hope to religious piety and the effects of war. Her political genius in helping to consolidate an empire, however, is often overlooked. Her literary contributions were so impressive that one tends to forget the reason why she was sent to Ur in the first place or the significant role she played in helping to blend the different religious traditions and cultures.

In her lifetime, and for centuries following, she was honored as a great poet and writer. According to scholar Gwendolyn Leick, “She made an enormous impression on generations of scribes after her lifetime; her works were copied and read centuries after her death”(120). Through Enheduanna's brilliance in crafting a pantheon of gods all of Mesopotamia could believe in, she helped lay the spiritual foundations for the first stable multi-cultural, multi-lingual, empire in the world; and through the works she left behind she influenced and inspired centuries of writers and poets in their creation of the literature which has touched millions of lives and helped to shape whole civilizations for thousands of years.

Author's Note: Many thanks to reader Elizabeth Viverito for insights shared on Enheduanna's work.