The storming of Bristol, a port then second only in importance to London, on 26 July 1643 by Royalist forces led by Prince Rupert (1619-1682) was a major coup against the Parliamentarians during the English Civil Wars (1642-1651). The Royalists were able to break through the long perimeter fortifications, which were manned by a defensive force spread too thinly. Taken in a day but with many casualties on both sides, Bristol became a vital Royalist centre until its fall to the Parliamentarians after the siege of 1645.

From Edgehill to Bristol

King Charles I of England (r. 1625-1649) considered himself an absolute monarch with absolute power and a divine right to rule, but his unwillingness to compromise with Parliament, particularly over money and religious reforms, led to a civil war from 1642 to 1651. Fought between the 'Roundheads' (Parliamentarians) and 'Cavaliers' (Royalists) in over 600 battles and sieges, the war was a long and bloody conflict. The northern and western parts of England largely remained loyal to the monarchy but the southeast, including London, was controlled by Parliament. The Parliamentarians also controlled the Royal Navy, a significant impediment to Charles receiving reinforcements from the Continent and Ireland. The king would need a port if the war dragged on, but if he could capture London in a decisive engagement, perhaps the war would be quickly over. Charles made his intent clear and raised the royal colours at Nottingham on 22 August 1642.

The first major engagement of the war had been the Battle of Edgehill in Warwickshire on 23 October 1642, which ended in a draw. Charles then delayed and captured Oxford before turning on London, where he was rebuffed by the presence of a 20,000-strong Parliamentarian army at Turnham Green. The king decided to fight another day and retreated to Oxford, which became the Royalist capital. A series of skirmishes and small-scale battles followed over the next year as neither side sought to commit all of their troops in a single field engagement. Rather, both sides concentrated on capturing what strategically valuable towns and cities they could. There were, too, half-hearted negotiations to bring peace through the winter and spring of 1643, but it seems that both sides were confident that they could press their advantage better on the battlefield when warmer weather arrived.

The indecisive nature of the war so far had not helped the Royalists in their predicament concerning sea power. In the summer of 1643, Prince Rupert, Count Palatine of the Rhine and Duke of Bavaria, Charles' nephew and commander of the Royal cavalry, was tasked with capturing Bristol, second only to London as the kingdom's most important port and an important regional military stronghold. Bristol was a major commercial centre, exporting such regional goods as cheese from the Wessex vales and importing many vital raw materials. It was a naval base and so could control the Irish Sea, and it was a major regional administrative centre. At the time, Bristol had a civilian population of around 15,000, making it the second-largest city in England after the capital.

Rupert, who was still only 23, had gained invaluable experience during the Thirty Years' War (1618-1648) in Central Europe. Rupert had been involved in the siege of Breda in 1637 and had fought well, if a little impetuously, in the Civil War so far, notably at Edgehill. Bristol was his next important target, but he would have to overcome the city's defences which he knew the value of, having himself advised the king (and been ignored) that Royalist cities should be heavily fortified.

The Attack

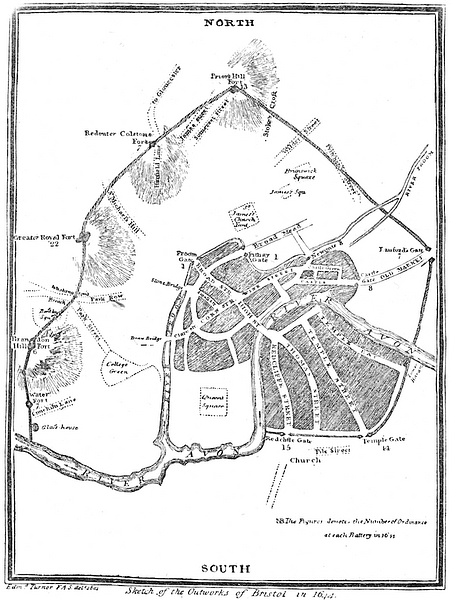

Bristol, like many Parliamentarian strongholds, was protected by a series of walls, earth banks, ditches, and individual fortifications, especially around the several gates that gave access to the city. The southern side was protected by the River Avon. The length of the fortifications at Bristol itself became a problem since the garrison consisted of only 300 cavalry and about 1,500 infantry who had to be spread over some 8 kilometres (5 miles) of walls, most of which dated to the Middle Ages. Some of these walls and the central castle were reinforced to take heavy artillery pieces. The city had around 100 cannons, but the situation of defence was not helped by needing to encircle the rise which overlooked the town since this position could not be lost to the enemy who might use it to station their own artillery batteries and bombard the town at will. On the other hand, such a large perimeter meant an attacking force could not fully encircle it either.

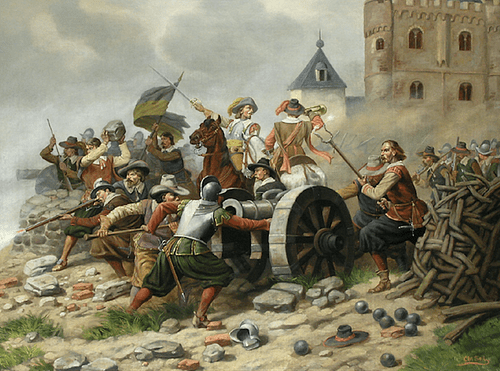

Given the city's defences, Rupert went for diplomacy first. As his army gathered at the city's walls on 24 July, an ultimatum was sent to the Parliamentarian governor Colonel Nathaniel Fiennes: surrender or face an attack. Fiennes was a man of little military experience or competence, as events would soon show. The governor refused the offer, and the attackers began their assault on the 26th. Assembled outside the city were 7,000 infantry of musketeers and pikemen and 7,000 cavalry. Also present was the king's latest secret weapon: one Bartholomew La Roche, a French expert in explosives who provided the Royalists with four wagonloads of ingenious and deadly 'infernal' devices such as grenades filled with either pieces of metal or inflammable liquid. La Roche was given the impressive title of 'Captain General of all Masters of Artificial Fires'. There were only eight cannons, though. This disappointing number was because horses could not be found to drag others to the site and the fact that, at this stage in the war, the Royalists still lacked a proper siege train. Neither did Rupert have very much ammunition for his artillery. The taking of Bristol would have to be by storm rather than attrition. The initial two-pronged attack was described as follows by a Royalist captain, Richard Atkyns:

When we came to Bristol, Prince Rupert (whose very name was half a conquest) with the Oxford army lay before it on the west side, and Prince Maurice (Prince Rupert's brother) with the Western army on the East: both armies not being half enough to besiege it; our Cornish foot were to fall on first, which they performed with a great deal of gallantry and resolution; but proving the stronger part of the town, they were beaten off, with a great deal of loss; when they found it inaccessible, they got carts laden with faggots, to fill up the 'graft' [moat]; but it being so deep, and full of water they could do no good upon it; but as gallant men as ever drew sword (pardon the comparison) lay upon the ground like rotten sheep…howsoever this loss of ours drew the town forces that way, which might be some advantage to Prince Rupert's forces, who stormed that part of the town with such irresistible courage, that forced them from their works, and gave them admission to the horse.

(Hunt, 116)

The situation became so desperate that even a body of 200 women volunteered to repair a section of earthworks near the Froome Gate. Meanwhile, Rupert managed to lead his cavalry into the city, an action described as follows by the Earl of Clarendon:

The enemy, as soon as they saw their line entered in one place, either out of fear, or on command of their officers, quit their posts; so that the Prince entered with his foot and horse into the suburbs, sending for one thousand of the Cornish foot…marched up to Froomgate, losing many men and some very good officers by shot from the walls and windows. All men were much cast down to see so little gotten with so great a loss; for they faced a more difficult entrance into the town than they had yet passed, and one where the horse could be no use to them. Then, to the exceeding comfort of generals and soldiers, the city beat a parley.

(ibid)

The governor had withdrawn his forces into the inner city rather than have them counterattack, an action which could well have repelled Rupert's force. Fiennes, despite still having significant forces in reserve and being in control of the fortifications on higher ground, then decided to surrender on the promise to allow him and his force to withdraw from the city. This condition was not honoured by the Royalist troops who harassed the Parliamentarians as they fled Bristol, although the mix-up was because Fiennes had led his men out of a different gate from the one he had agreed to exit the city. According to one Puritan witness, the Royalists attacked men, women, and children, robbing them of anything valuable, even their clothes. This was a fairly typical fate for most of Bristol's inhabitants as the soldiers indulged in their usual round of indiscriminate looting in the city.

There was to be no safe haven for Fiennes as, upon reaching Royalist-held territory again, he was tried and condemned to death for his surrender, but he was later reprieved. The loss of Bristol was certainly a significant one for the war. An added bonus to the strategic gain was the taking of three warships in the harbour. Bristol came under the rule of the Prince of Wales, future King Charles II of England (r. 1660-1685), who resided there.

Aftermath

The capture of Bristol was followed by the indecisive First Battle of Newbury in September 1643 and then the failure to capture Gloucester in October, which was much more resolutely defended than Bristol had been. The royal infantry losses at Bristol, especially of officers, persuaded the king to besiege and not directly storm Gloucester, which was then relieved by a Parliamentarian army. The material losses at both these battles also delayed the king's much-expected drive on London. Generally, though, 1643 was a good year for the Royalists. They had captured several important cities and gained much territory. Bristol's fortifications were rebuilt, with a curtain wall reaching a height of 1.82 metres (6 ft) in places. The port became an important importer of materials for the war effort and a manufacturing centre of arms, producing 200 muskets and bandoliers each week in 1644. That year, though, would see the Parliamentarians steadily gain the upper hand in the war. The port, meanwhile, would remain in Royalist hands until the siege of Bristol in 1645 and the disastrous loss in September by Prince Rupert, which brought him disgrace and banishment from his king's presence.