The First Battle of Newbury on 20 September 1643 was a major engagement between Royalist and Parliamentarian armies during the English Civil Wars (1642-1651). The Royalist forces loyal to Charles I of England (r. 1625-1649) were led by Prince Rupert (l. 1619-1682) and faced an army led by the Earl of Essex. This, the longest battle of the Civil Wars, saw high casualties on both sides and ended in a draw, albeit one more satisfactory to the Parliamentarians, who had once again scuppered any plans the king might have had of capturing London.

From Edgehill to Newbury

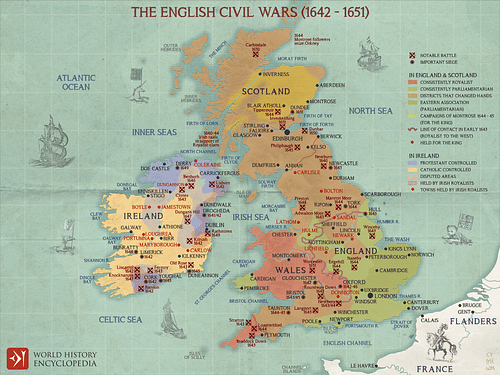

King Charles I of England (r. 1625-1649) considered himself an absolute monarch with absolute power and a divine right to rule, but his unwillingness to compromise with Parliament, particularly over money and religious reforms, led to a civil war from 1642 to 1651. Fought between the 'Roundheads' (Parliamentarians) and 'Cavaliers' (Royalists) in over 600 battles and sieges, the war was a long and bloody conflict. The northern and western parts of England largely remained loyal to the monarchy, but the southeast, including London, was controlled by Parliament. The Parliamentarians also controlled the Royal Navy, a significant impediment to Charles receiving reinforcements from the Continent and Ireland.

The first major engagement of the war was the Battle of Edgehill in Warwickshire on 23 October 1642, which ended in a draw and prevented the king from marching on London. This was followed by a number of small-scale battles and skirmishes. The Storming of Bristol in July 1643 then gave the Royalists a vital port and arms manufacturing centre. The attack had been orchestrated by Prince Rupert, Count Palatine of the Rhine and Duke of Bavaria, Charles' nephew and commander of the Royal cavalry. The Parliamentarian cause was then boosted by holding on to Gloucester, despite being under siege in August and September. At the same time, Royalist sieges at Hull and Plymouth were floundering. One year in, the war was still finely balanced.

Battle

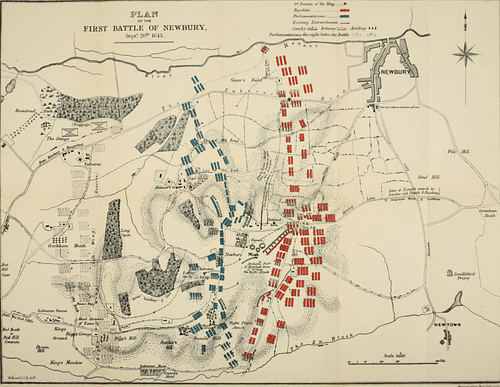

A Parliamentary army led by Robert Devereux, the Earl of Essex (l. 1591-1646) had relieved Gloucester, and this force now faced the Royalist army led by Prince Rupert at Newbury in Berkshire on 20 September. With up to 15,000 men on each side, this was the largest battle of 1643. The Royalists likely had more cavalry while the Parliamentarians had a numerical advantage in infantry. Essex commanded two divisions of infantry (with around 5,000 men in each), six regiments of cavalry, a number of companies of dragoons (hybrid infantry-cavalry), and units of heavy artillery. Essex seems to have determined to march his army eastwards and meet the Royalists before they could be trapped in a defile that led to the nearby village of Enbourne.

The battlefield was largely meadows and hedged fields with a low but long and crescent-shaped rise known as Round Hill in the southern portion of the area of action. The varied terrain with shallow gorges, lanes, and hedgerows meant that some units on both sides – for example, the left wing of the Parliamentary cavalry – could not fully participate in the main battle areas. This was especially so following Essex's decision not to stand static but to move his army and split up his two infantry divisions, one operating as a reserve. The strategy was perhaps partly due to Rupert having gained an early advantage when a vanguard of his cavalry captured some food supplies which had been rounded up from the local communities and destined for the Parliamentarian army. Consequently, Essex could not await expected reinforcements coming from the south and was obliged to engage the enemy whilst at the same time making some effort to move to an area where supplies could be found.

Both sides had infantry formations composed of formidable groups of pikemen, who wielded pikes, ash poles some 5.5 metres (18 ft) in length and topped by a long metal spike. Supporting the pikemen in small groups were musketeers armed with matchlock muskets and who typically operated in ranks to present volley-fire. Cannon fire was highly effective from both sides, as attested by one eyewitness, Captain John Gwyn, who "saw a whole file of men, six deep, with their heads struck off with one cannon shot" (Henry, 37).

Round Hill

Essex's artillery was particularly effective as they had taken over Round Hill in the first hour of the battle. According to the military historian M. Wanklyn, rather than a point of defence, Essex intended to use the hill to create a covering fire while his army forced their way to more open ground, and in so doing they would outflank the enemy. Rupert may well have realised his opposing commander's intentions, and so he attacked with speed using his cavalry and infantry before Essex's troops could properly organise themselves. It was possible to effectively mobilise the Royalist artillery according to the shifting battle situation thanks to the presence of numerous lanes crisscrossing the area which aided the movement of the horse-pulled gun carriages. However, the royalist musketeers were driven back from their initial attack on what had become the pivotal point of the battlefield: Round Hill.

The Royalists threw a sizeable chunk of their army – infantry, cavalry, and dragoons at Round Hill in a second attempt to drive the enemy down the back of the rise. The fighting was intense and the casualties heavy on both sides, but the Royalists did succeed in taking a small hill next to Round Hill. Essex reinforced his men on Round Hill and succeeded in preventing the enemy from making further inroads up the rise. Meanwhile, there was a sizeable clash of cavalry on the right flank of the Parliamentarian army. The Royalists had now split up their artillery, which was being used effectively in small pockets, each with cavalry support.

Nightfall

As night fell, the fighting continued in various areas of the battlefield, a notable action being the Parliamentarian attack on the Royalist ammunition train. Confusion had reigned throughout the day. The broken terrain and the use of hedgerows for cover by artillery and musketeers on both sides meant that some areas of the battlefield witnessed heavy fighting while in other areas some units saw no fighting whatsoever.

As night drew on and the fighting finally ceased, the Royalists likely had a slight advantage. The king, present in person but well away from the action, still had forces stationed west of Newbury and expected more troops to arrive from Bristol within 48 hours. Essex, on the other hand, had not succeeded in moving his army and still needed food for it. Neither was there much water available where they were. On the other hand, the Parliamentarians still had control of Round Hill. There had been high casualties on both sides.

Stalemate

As light dawned on the second day, so did the realisation that the Royalists could not continue the battle. They had used up a prodigious amount of gunpowder the day before – perhaps 80 barrels – and their ammunition was desperately low. Despite knowing that time was otherwise on his side, the king was obliged to withdraw back to his capital at Oxford. Essex, meanwhile, compacted his various divisions and marched off to the east. The Parliamentarians were occasionally troubled by the odd Royalist cannonball, and one sortie by Rupert's cavalry caused some damage to the Parliamentarians' left wing, but, otherwise, the engagement was over. Men and horses were exhausted on both sides.

The result of the battle was, as so often in the larger field engagements during the Civil War, indecisive. Not for the first time in the conflict, the Royalist cavalry had been superior, but once again the Parliamentarian infantry had more than matched the enemy. In effect, Essex had removed any threat to London, for the time being, at least. His army regrouped at Reading and then moved on to Windsor. When the Parliamentarian general finally made it back to the capital, he was greeted as if he had won a great victory, and the city's very own militia, the London Trained Bands, were welcomed as returning heroes. Not perhaps a Roman triumph, Essex was at least recognised for his strategic victory. Once again, he had ensured that the king and his army remained banished from the political and commercial capital of his thoroughly divided kingdom.

Aftermath

Both of the Royalist sieges at Hull and Plymouth fizzled out with high casualties and no positive result for the king's men. As 1643 came to a close, it was becoming clear that as the war dragged on, Parliament's superior resources would eventually be telling. Another major boost to the Parliamentarians came in December with the alliance forged with the Covenanters of Scotland, who sought to defend the independence of the Presbyterian Church there, something that a Royalist victory in England seemed now to threaten. 1644 would witness another string of battles, including two major ones: the Battle of Marston Moor in July and at the Second Battle of Newbury in October, the first being a Parliamentary victory and the second, once again, with an indecisive result that ensured the English Civil Wars rolled on. It was not until 1645, which saw the formation of the professional New Model Army by the Parliamentarians and the rise of Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658), that just who would win this bloody conflict became more evident.