In Norse mythology, the Sun and the Moon appear as personified siblings pulling the heavenly bodies and chased by wolves, or as plain objects. Written sources, such as the Poetic Edda and the Prose Edda, have surprisingly little to say about them, but clues from before the Viking Age put together with the written works speak of their greater role in ancient Scandinavia.

The Sun & Moon in Norse Writings

Unlike in the Roman tradition and much like in modern German, the sun (sól in Old Norse) is a feminine noun, and the moon (máni) is masculine. In the Völuspá, a poem where a prophetess reveals information about the beginning and end of the world, we can read about their kinship:

The sun, sister of the moon,

Shone from the south,

With her hand

Over the rim of heaven;

The sun did not know yet

Where her home should be,

The moon did not know yet

What power he had(stanza 5)

In the Vafþrúðnismál ("Ballad of Vafthrudnir"), where Odin engages in a contest of mythological knowledge with a giant, they seem to be personified. Their father is called Mundilfari, which would mean something like "The Turner", the one who comes and goes periodically, a probable reference to the movement of the celestial bodies.

He is called Mundilfari,

Father to the Moon

Also father to the Sun;

They will float

On the sky every day,

So we can tell time.(stanza 23)

The moon is mentioned first, and 'Mundil' may be related to 'mund', a time period, which could be explained by the simple fact that for the Norse, the day began at night, and the year in winter.

According to the same ballad, the sun would be swallowed by the wolf Fenrir, one of the monstrous sons of Loki, the one who chopped off the hand of the god Tyr when assigned to bind him with a magic rope. The typical motif of the sun swallowed by a monster could be linked to observations people made about the rising and setting of the sun, or eclipses and the fear such phenomena might have caused.

The elf-disc (sun)

Bears a daughter

As soon as Fenrir eats her;

When the gods have died

She treads her mother's path.(stanza 46-47)

These events are also echoed in the Völuspá, where the prophetess mentions the moon would soon be stolen by one of Fenrir's children with a giantess. Elsewhere in Völuspá, for example when presenting the signs of Ragnarök, the twilight of the gods and the upcoming battle, the sun turns black while the earth sinks into the sea, thus it does not appear personified.

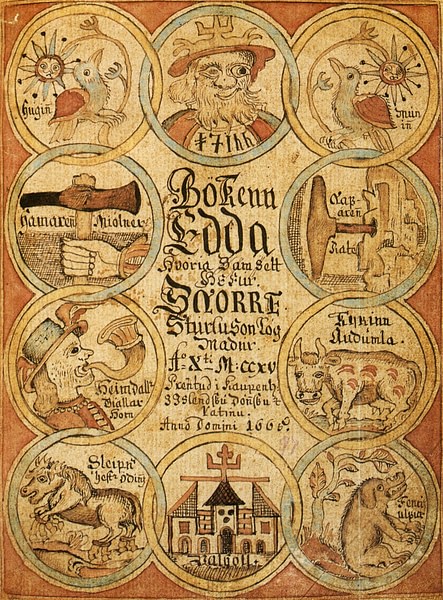

From all these bits and pieces, the 12th-century Icelandic scholar Snorri Sturluson attempted to relate an understandable story, with details not included anywhere else. In Gylfaginning, the first part of his Prose Edda, a legendary Swedish king named Gylfi embarks on a journey for knowledge about the world. Among many other things, he asks the gods about the origin of the sun and moon. As told by Snorri, the man Mundilfari has two fair children, and he marries off his daughter Sól to a man called Glen. This reckless act angers the gods who "took the siblings and put them in heavens, let the Sun drive those horses dragging the chariot of the sun which the gods made to lighten the world from the glowing stuff coming out of Muspellheim" (Faulkes 2005). Muspell would be the realm of fire and home to the fire-giants.

The story goes on to mention the names of the horses, Árvakr and Alsviðr, meaning "early-awake" and "very quick", which we can also find in the Poetic Edda. They possess some kind of windbag to keep them cool. The Ballad of Vafthrudnir, however, mentions Skinfaxi ("shining-mane"), who brings us the glittering day, and Hrímfaxi ("frost-mane"), who brings the night and also the dew from his foam. As for the other character, Máni, he would steer the course of the moon and determine its phases. On this task he gets two helpers, the children Bil and Hjúki, bearing on their shoulders a cask and pole and whom we can see from earth. Unfortunately, it remains quite an enigma what Snorri meant by that.

Furthermore, Snorri talks about the end of the sun and moon. The Swedish king remarks that the sun hastens as if she were afraid and as if an impending doom were chasing her. Another deity confirms that she does hasten furiously but has no escape, given what follows her:

There are two wolves, and Skoll is the name of the one chasing her. She fears him, and he will get her; the one leaping in front of her is called Hati, son of Hrodvitnir [Fenrir probably], and he will get the moon, so it must be. (Faulkes 2005)

According to Snorri, who also offers advice to poets in his section called Skáldskaparmál, there seems to be a link between shields and the sun or moon, a reminder of the ritual shields used in the Bronze Age. He suggests that shields may be called sun, moon, leaf, or garth of the ship and that it was common to draw a circle, called the ring, on ancient shields. In the same text, Snorri tells poets to call the sun fire of heavens and air. Other figurative phrases found in the Poetic Edda focus on its gold-like brightness. As objects of great importance, and not necessarily deities, the sun and moon can be requested as a reward for a deed. In the Gylfaginning, when the Æsir, the godly family residing in Asgard, need a strong citadel to defend them from enemies, they assign the task to a smith-giant who demands in return goddess Freyja, the lady of love, fertility and battle, as well as the moon and sun.

Images of the Sun

Why there are so few resources on the sun in Norse myth, despite the large archaeological evidence pointing out its immense relevance for the peoples of the Bronze Age, could be either due to a loss of material or meaning or to an evolution into other deities that captured its attributes. Among the clues pointing to this direction is the motif of the sun chariot. The journey of the sun on a wagon during the day and beneath the sea in a ship at night was quite a universal pattern in the early civilisations of Europe. On the other hand, in Norse myth, we have a few images of the fertility gods, Freyja and Freyr as well as Njord, vaguely associated with the sun. The movement of the sun in the sky is, moreover, linked to seasonal change and vegetation growth.

In prehistoric Scandinavia, images of the sun being held by humans, set on a ship or wagon, appear on slabs inside graves, sun-like shields, belt plates and the famous 1400 BCE Trundholm sun-chariot, where it is depicted as drawn by a horse on its eternal journey, both set on wheels suggesting continuous motion. As we have seen, the Edda also presents the sun travelling across the heavens dragged by two horses, suggesting a unification of the two motifs, the sun myth and the god(dess) on a wagon. The Celtic Gundestrup Cauldron from the Iron Age presents such a travelling deity accompanied by several animals – the artefact is richly decorated on all the plates, sometimes with complicated scenes like a warrior procession and a god with antlers. On the Gotland picture stones, we can find images of whirling discs (the Hablingbo, Sanda, Ire, Garda stones), as well as riders and drinking horns, very popular in the Viking Age. Furthermore, magnates were accompanied to the grave by ritual wagons as discoveries at Kraghede, Vendsyssel and Langå on Funen island attest.

When talking about the Germanic tribe of the Suebi, 1st-century CE Roman author Tacitus describes, in his ethnographic work Germania, the holy chariot of the goddess Nerthus, Mother Earth, placed in the woods on an island where sacrifices were made. He relates that the consecrated chariot is draped with cloth, only a priest may touch it, and during her contact with human society weapons are fobidden, there are days of rejoicing until the goddess gets washed in a hidden lake. Nerthus is in fact the same word as Njord in Old Norse, a male deity, patriarch of the Vanir family of gods, making us wonder if they initially had been a pair of deities who ended up as one and then shared their characteristics with their children Freyr and Freyja. The existence of a male priest for Nerthus and female priestesses for Freyr could also suggest the existence of counterparts. Norse mythology provides a different wife for Njord though, Skadi, linked to skiing and winter.

In Snorri's Ynglinga Saga, a legendary saga that begins his chronicle of the kings of Norway and where the gods are humanised, Freyr rules as a king of Sweden after Njord. Because his days of rule bring peace and good seasons, he is worshipped as a god of harvest after his death. These deities, travelling in carts and bringing vegetation and growth, may have integrated the role of solar deities.

Apart from the more obvious connection with the fruitfulness of the Earth and yearly revival, the sun setting on a ship could also relate to death and the underworld. Carvings with chariots and bird shapes put in graves were probably intended to guide or protect the dead. The horse also had special importance in the burial practices of the Vikings as a means of communication between the two worlds, therefore a sun drawn by horses might have meant more than just the solar motion. As for the bird shapes or bird-shaped women, they might vaguely remind us of the Valkyries taking half of the dead warriors to Valhalla; the other half goes to Fólkvangr, Freyja's hall. On the other hand, Odin, the god with leadership and warmongering traits, can shapeshift into an eagle, a symbol of power and strength. Thus in some way, all these elements, wagon, wheel, bird, horse come together in the theme of an underworld hinted at by the motion of the sun-chariot as well.

The other image popular in the Bronze Age, that of the sun on ship, can easily parallel traditions elsewhere, such as the Egyptian sun god Ra or Apollo from Greek mythology who gave protection in navigation. This image is used to describe shields: in Snorri's poetic teachings the shield can be a skipsól, literally a ship-sun, or a hlýrtungl, prow-moon.

Transformed Solar Deities?

The question of whether the pair Freyr and Freyja could somehow be considered solar gods does not allow an easy answer. Freyja's connection to the sun can only be derived from her qualities very indirectly, as the fair and shining one, possessing wealth such as the Brisingamen, the necklace glowing like fire. As a possessor of the slain, taking fallen warriors to her hall Sessrúmnir, she has been said to function as a model for the Valkyries, bearing shields on horseback. If we accept the shield's association with the sun and take into account Freyja's riding in a chariot, possessing shiny treasure or traits like red-gold tears, the solar connection might work.

Freyr's solar dimension could be inferred from several mythological details. In Gylfaginning, he is specifically named the most glorious of the gods and his sister the most glorious of the goddesses: "He is the ruler of the rain and sunshine and thus of the fruits of the earth, and it is good to pray to him for prosperity and peace. He also rules over the wealth of men" (chapter 24). Besides the fertility aspect evident in this quote, we have extra elements from the solar sphere: his boar Gullinbursti ("golden bristles"), his servant Skírnir ("the bright one"), and a ship that can also form an image with the sun. At the end of the world, Freyr will battle the fire giant Surt, which could be understood as a reference to the destructive side of the sun. Either way, because of the god's qualities to offer prosperity and good harvest, a solar role can be implied.

We should, however, not forget that Norse gods usually had multiples roles, and given the inconclusive material, it would be exaggerated to consider Freyr and Freyja as proper sun gods. Broadly speaking, whatever sun or moon deities pagan Scandinavians were worshipping before the Viking Age, they fell into oblivion by the time the Norse myths were written down, and we can only speculate that perhaps some of their characteristics were merged with other deities. Interestingly, one of the Merseburger charms, two incantations written in Old High German and found in a 9th-century manuscript, mentions someone named Sunna in the context of invoking the gods to heal a foal's foot. A vague trace of the original sun goddess, perhaps.