The Epic of Gilgamesh is among the most popular works of literature in the present day and has influenced countless numbers of readers but, for the greater part of its history, it was lost. The Assyrian Empire fell to a coalition of Babylonians and Medes in 612 BCE who sacked and burned the Assyrian cities and, among them, Nineveh.

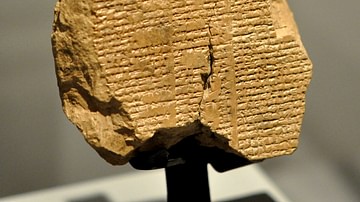

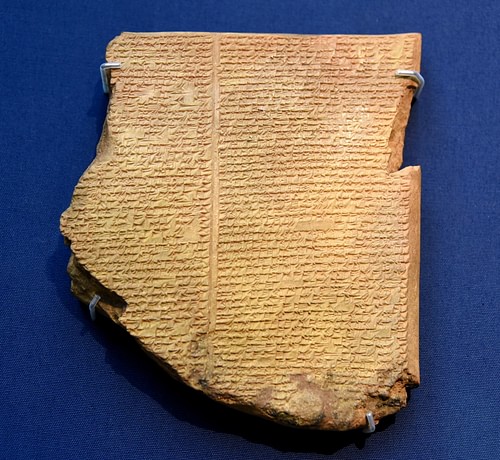

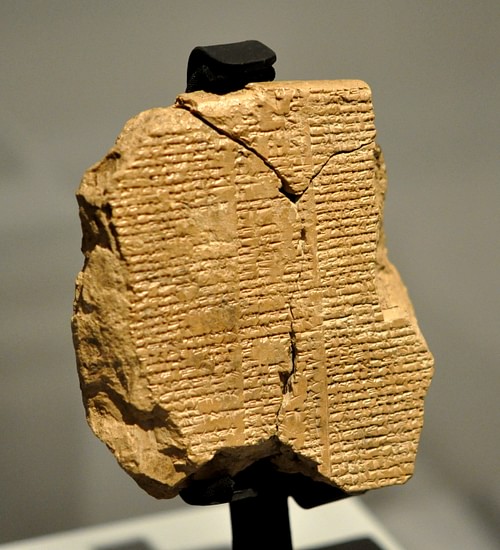

Nineveh was the great capital where the king Ashurbanipal (r. 668-627 BCE) had established his library which housed copies of every literary work he could find throughout Mesopotamia. As these works were written in cuneiform on clay tablets, however, the fires which consumed the library did nothing to the tablets but bake and better preserve them. Even so, the buildings which housed these works were destroyed, burying the literature of Mesopotamia beneath them for over 2,000 years until they were re-discovered in the mid-19th century.

At that time, European antiquarian societies, museums, governments, and other institutions sent archaeologists to Mesopotamia in the interests of finding physical evidence which would corroborate narratives in the Bible. Since Mesopotamian sites and kings were so frequently mentioned throughout the Old Testament, it was thought that a concerted effort in excavation would prove the narratives true. This was especially important at this time as Darwin's work had been gaining in popularity since its publication in 1859 and people were questioning the historical reliability and authority of the Bible.

What these excavators discovered was actually the exact opposite of what they were sent to find. As they uncovered the ruins of the ancient cities of Mesopotamia, they found the cuneiform texts which, once deciphered, clearly showed that some of the most famous stories in the Bible - the Fall of Man, the Great Flood and Noah's Ark - were later versions of Sumerian myths and legends.

The Mesopotamian excavations of the 19th century literally changed world history because now it was understood that the Bible was not the oldest book in the world, that civilizations had flourished for thousands of years before the biblical date of the creation of the world, and these civilizations had actually created many of the technologies, innovations, belief structures, and literary genres which had been ascribed to later peoples.

Among these genres was the heroic epic - long thought to have been created by Homer in Greece (c.8th century BCE) - but now understood to have been a Mesopotamian innovation. The Epic of Gilgamesh was discovered by the modern world in 1849 by the British explorer and archaeologist Austen Henry Layard. The fullest surviving version, in the Akkadian language, was found on clay tablets of cuneiform in the ruins of the ancient library of Ashurbanipal in Nineveh.

The first eleven tablets relate the standard version of the epic while the 12th tablet narrates an older Sumerian poem Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld. As this story contradicts the tale told in the first eleven (in that Enkidu, who dies in tablet 7, is somehow alive again), it is not included in most standard versions of the tale. According to some scholars, Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld is an early, possibly the first, appearance of the great hero-king, written down from an older oral tradition during the Ur III Period (2047-1750 BCE), though other scholars cite c. 2100 BCE as the earliest evidence of Gilgamesh's story. Even so, with or without the tale in the twelfth tablet, The Epic of Gilgamesh is a stunning literary achievement which remains a best-seller thousands of years after it was written and confers upon its hero that which he sought throughout his story: immortality.

Origins of the Story

The Epic of Gilgamesh was originally a series of Sumerian poems, later translated into Akkadian, and first written down some 700 – 1000 years after the reign of the historical king of Uruk upon whom it is based. The poem was known originally as Sha-naqba-imru (He Who Saw The Deep) or, alternately, Shutur-eli-sham (Surpassing All Other Kings). The character was already developed in earlier Sumerian works as a great hero and demi-god, brother of the goddess Inanna, and a mighty warrior but, in the epic, he is transformed into the embodiment of the human struggle against death, loss, and the apparent meaningless of existence.

The author of the epic is Shin-Leqi-Unninni (whose name translates as `Moon god, accept my plea') a Babylonian scribe who wrote c. 1300-1000 BCE and has been cited as the first author in the world known by name even though that honor is rightly accorded to the poet-priestess Enheduanna (l. 2285-2250 BCE), daughter of Sargon of Akkad (r. 2334-2279 BCE). Orientalist Samuel Noah Kramer points out that Shin-Leqi-Unninni did far more than simply translate and copy an earlier Sumerian work, he created something wholly new from older sources and this "something new" was the heroic epic (Sumer, 270). According to the scholar N.K. Sandars, the work is “the finest surviving epic poem from any period until the appearance of Homer's Iliad; and it is immeasurably older”(Sandars, 7).

The hero of The Epic of Gilgamesh is the half-legendary King of Uruk who, according to the poem, felled the great trees of the Cedar Forest with his friend Enkidu to build the mighty gates of the city and journeyed far to find the secret of eternal life from the seer Utanapishtim. It is generally accepted that Gilgamesh was the historical 5th king who ruled in Uruk (widely regarded as the birthplace of writing) c. 2500 BCE.

Archaeological finds of letters and inscriptions attesting to his deeds, and those of his son, provide no reason to doubt such a man existed. In 2003, in fact, a team of archaeologists claimed to have found Gilgamesh's tomb in the old riverbed of the Euphrates.

The deeds of this king were so great that, in time, the man was transformed from a mere mortal to a god. His father is said to have been the Priest-King Lugalbanda and his mother was the goddess Ninsun (also known as Rimat-Ninsun Ninsumun), the Holy Mother and Great Queen, whose name is interpreted as `August Cow' or `Wild Cow of the Enclosure' thus making Gilgamesh a demi-god of extraordinary endurance and strength but, also, mortal.

While Gilgamesh could, and did, perform many great feats, he could not finally realize his greatest desire to conquer death, to live eternally – or could he?

The Quest for Eternal Life

According to The Epic of Gilgamesh, the great king, arrogant and cruel among the lesser beings he ruled, was sent a strange gift from the gods: the wild man Enkidu who would be a challenge to Gilgamesh's strength and, perhaps, teach him humility.

Enkidu, originally without law and running wild in the forests, is seduced and thereby tamed by the temple harlot Shamhat, and is brought to Uruk where he, as intended, challenges Gilgamesh. After they fight, and Enkidu is bested, the two vow eternal friendship and Gilgamesh's mother Ninsun adopts Enkidu as her own.

Following the battle of the Cedar Forest in which they defeat the demon-monster Humbaba (demon to be understood as supernatural, not evil) and, soon after, the Bull of Heaven (insulting the goddess Inanna-Ishtar along the way) the gods decree the death of Enkidu, claiming that someone must pay the blood price for such deeds. Humbaba was innocent of any wrong-doing and was loved by the gods and the Bull of Heaven was the husband of the underworld goddess Ereshkigal. Neither deserved the death given them by Enkidu. Enkidu dies and, in that moment, Gilgamesh realizes that he, too, will die and this knowledge torments him. He cries out:

How can I rest, how can I be at peace? Despair is in my heart. What my brother is now, that shall I be when I am dead. Because I am afraid of death I will go as best I can to find Utnapishtim whom they call the Faraway, for he has entered the assembly of the gods. (Book 9; Sandars, 97)

After a journey across the Land of Night and the Waters of Death, Gilgamesh finds the ancient man Utanapishtim, the only human being to survive the Great Flood who was, afterwards, granted immortality. Utanapishtim tells Gilgamesh the story of how he was warned by the god Ea of the coming deluge, followed his command to build an ark and place assorted animals inside and so save himself and his family from death and humanity from extinction.

He then tells Gilgamesh eternal life will be granted if he can stay awake for the next six days. Gilgamesh fails in this and fails in his next attempt, to bring back a magic plant which will make one young again. The plant is eaten by a snake while Gilgamesh sleeps; thus explaining why snakes shed their skins (they gained immortality from the plant). Having failed to win eternal life, Gilgamesh is brought back to Uruk by the ferryman Urshanabi where, once home, he writes down his great adventure. According to the scholar D. Brendan Nagle:

This magnificent poem, which deals with such eternal human problems as sickness, old age, death, fame and the craving for the unattainable, can be considered a metaphor for Mesopotamia's own heroic struggle to resist decay and leave a name for itself among the peoples of Earth. (16)

However true that may be, the epic is, at heart, the eternal struggle of the individual to find meaning in existence. Sandars writes:

If Gilgamesh is not the first human hero, he is the first tragic hero of whom anything is known. He is at once the most sympathetic to us, and most typical of individual man in his search for life and understanding. (7)

While Gilgamesh may have failed in his quest for immortality in the epic and the historical king is known only through passing references, lists and inscriptions, he lives on eternally through the work of Shin-Leqi-Unninni and the many other, now nameless, scribes who wrote down the orally transmitted tale and translated the story laboriously generation to generation.

These scribes attribute the original source of the story to Gilgamesh himself who, allegedly, inscribed his great deeds and adventures on a huge stone by the gates of Uruk ( or on the walls of the city). As scholar Gwendolyn Leick notes, Gilgamesh thus “became immortal by making a significant contribution to the greatness of his city by availing himself of the city's ultimate cultural invention: writing” (56).

Through the written word, the story of Gilgamesh and his pride, his grief for the loss of his loved friend, his fear of death and quest for eternal life, the great king does, in fact, conquer death and wins his immortality each time his tale is read.