The siege and capture of Bristol by Parliamentary forces on 10 September 1645 was one of the most devastating blows to the Royalist cause during the English Civil Wars (1642-1651). King Charles I of England (r. 1625-1649) had entrusted the city's safekeeping to his nephew Prince Rupert (1619-1682), but he could not hold out against the New Model Army led by Sir Thomas Fairfax (1612-1671).

The Decline in Royalist Fortunes

King Charles had clashed with Parliament, particularly over money and religious reforms for years, and, finally, a civil war broke out in 1642. The 'Roundheads' (Parliamentarians) and 'Cavaliers' (Royalists) met in over 600 battles and sieges over the duration of the conflict. The Royalists controlled the southwest while Parliament had, by 1645, gained sway over most of the rest of England. The king's chances of winning the war were greatly reduced by such defeats as the Battle of Marston Moor (July 1644) and the Battle of Naseby (June 1645). The Parliamentarians had reorganised their armies to great effect, creating the New Model Army with a new and much more effective command structure. The two commanders in the field, Sir Thomas Fairfax and Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658), were both experienced and talented. Naseby had seen the destruction of the king's infantry, and a Royalist cavalry army led by Goring was defeated at Langport on 10 July 1645. The Parliamentarians, now certain of victory in the war, focussed on the Royalists' crucial port and centre of arms manufacturing: Bristol.

Bristol: A Thriving Port

Bristol, located on the western coast of England, had already been fought over once during the Civil War. As England's second most important port after London, it was a valuable prize indeed. The storming of Bristol in July 1643 had been led by Prince Rupert, Count Palatine of the Rhine and Duke of Bavaria, and its success gave the Royalists the possibility of importing materials and men from Ireland and the Continent. Bristol was a major commercial centre, exporting such regional goods as cheese from the Wessex vales and importing many vital raw materials. The port became an important importer of goods specifically for the war effort and a manufacturing centre of arms, producing 200 muskets and bandoliers each week through 1644. Bristol was also a naval base and so could control the Irish Sea, and it was a major regional administrative centre. At the time, Bristol had a civilian population of around 15,000, making it the second-largest city in England after the capital. Royalist Bristol came under the rule of the Prince of Wales, future King Charles II of England (r. 1660-1685), who resided there.

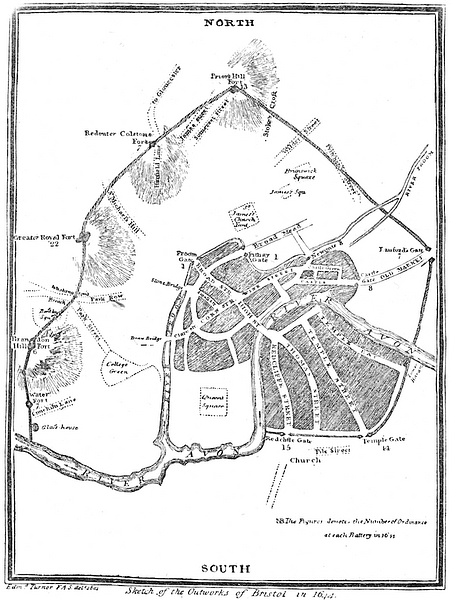

Bristol's Defences

In anticipation of the Parliamentarians making an attempt to recapture the city, Bristol's fortifications were rebuilt. The city had a curtain wall reaching a height of 1.82 metres (6 ft) in places and not less than 1.2 metres (4 ft) in others. Additional earthworks connected each outer fort to create a complete line of defences on three sides, the fourth side being protected by the River Avon. Fort Royal was further strengthened after it had already been rebuilt with five bastions giving it what was then considered the perfect defensive form of a pentagon.

Ditches around 1.5 metres (5 ft) deep and 1.8 metres (2 yards) wide were dug outside the city and around individual forts to impede cavalry. Labourers and even tradesmen and shopkeepers were employed shovelling earth from one place to another, so much so there were complaints from residents that shops were too often closed. In the eventuality of any attacker's breaching the city's main defences, streets were blocked with barricades and chains. Although the defences were not completed as planned, no less a figure than Prince Rupert was charged with defending the city against the inevitable Parliamentary attack in the late summer of 1645.

The Siege Begins

The Parliamentarians began to circle in on Bristol, first capturing outlying Royalist garrisons, ensuring the city was left isolated. General Fairfax slowly began to surround the city. Prince Rupert, although he knew the vital importance of the city to his king's cause, had the exact same problem the Parliamentarians had had in defending the city two years earlier. The perimeter walls were over 8 kilometres (5 mi) long, and the garrison, depleted by the disastrous events of the war elsewhere, was not large enough to adequately defend such a stretch of fortifications. The Parliamentarians later claimed the Bristol garrison had an impressive 4,000 regular troops, but Prince Rupert afterwards stated that he had at his disposal less than half that figure. The truth lies, no doubt, somewhere between the two positions. The historian John Barratt states that "a reasonably accurate total for the Royalist garrison might be around 1,000 cavalry, together with 2,500 regular infantry and 800-1,000 Trained Band and auxiliaries" (38). The city's walls and various forts offered a combined firepower of 151 cannons, and Rupert had instructed the civilian population to stockpile at least six months' worth of supplies (although over half did not follow these instructions, perhaps convinced that the city would fall in any case).

There was, too, the hope that reinforcements might arrive from South Wales and even King Charles might be persuaded to assist with his own army of some 3,000-strong cavalry. The reality was, though, that since the Parliamentarians had overwhelmed Somerset and defeated Goring at Langport, the king was unwilling to risk his remaining cavalry in such a strategically isolated position as Bristol. If Rupert was to hold on to the city, he would have to do so alone.

General Fairfax arrived outside Bristol at the head of the New Model Army on 21 August. In a last-ditch attempt to hamper the coming attack, Rupert had the villages of Clifton and Bedminster flattened. Rupert also ordered that the outer suburbs of Bristol itself be pulled down, but understandably, many of the citizens refused. Fairfax, seemingly in no particular rush, established his headquarters at Keynsham and ordered his cavalry to drive the Royalists back within the city walls, preventing any further scorched-earth tactics to the north. Rupert again sent a cavalry force to see what damage they could do south of the River Avon on 22 August, but they were once again obliged to retreat. Fairfax was content to wait as more Parliamentarian troops arrived over the next few days.

With his army now covering both the southern and eastern sides of the city, Fairfax had a similar problem to the defenders: how to prevent his lines from being spread too thin opposite the city's long fortifications? The attackers dug in and erected their siegeworks while Fairfax shifted his command headquarters to Stapleton. Perhaps realising a complete blockade would be difficult to achieve, the Parliamentarians attempted to incite Bristol's civilian population into overthrowing the Royalist forces from within. This tactic failed, and Rupert persisted in his own strategy of harassing the enemy before they could fully encamp. A cavalry force was sent out on the 22nd and 23rd of August, but both achieved very little and were beaten back. A few more skirmishes occurred over the next week, but Fairfax continued his leisurely plan of slowly strangling the city into submission without launching any large-scale attack.

Rupert must now have been fully aware that inaction on his part would only end in ultimate defeat, and on 1 September, he personally led the largest sortie of the siege so far. Helped by foul weather and mist, the raid managed to capture a quantity of stores and a Parliamentary colonel before it was driven back like all the others.

Final Negotiations

By 3 September, the besiegers had been bolstered by a significant number of locals, and all seemed ready for the big assault, but the weather continued to be unfavourable. Fairfax now had to consider the usual problem of any commander with an army stationary in the field for any length of time: disease amongst his men. Action was required. Holding a committee meeting of senior commanders, Fairfax decided to avoid the strongly-defended northern side of the city and instead move on the south and east sides simultaneously. In a detailed plan of attack, combined cavalry and infantry forces were tasked with targetting specific forts along the city's defensive lines. There was even a reserve force of cavalry to meet any attempt by the Royalist cavalry to break out of the city.

Before the plan was put in action, and as per the standard approach to siege warfare of the period, on 5 September Fairfax sent word to Prince Rupert that he would now accept a surrender. Rupert may well have known his cause was hopeless, but he stalled for time. Not rejecting outright the demand for a surrender, he informed Fairfax that he would need to first communicate with King Charles on how to proceed. This may also have been a strategy to entice the king into sending reinforcements. Fairfax rejected the demand as time-wasting. On 6 September, Rupert sent Fairfax a communication of his own. Bristol would be surrendered on the condition that its citizens would not suffer any recriminations and there would not be a Parliamentary army garrisoned in the city. The latter demand was outrageous to the Parliamentarians and obviously another ploy to delay the attack. Letters then went backwards and forwards over the next three days until, on 9 September, Fairfax send his final ultimatum that unless Rupert surrendered a full-scale attack would follow the next day.

The Attack

With no surrender forthcoming, the attack began at 2 a.m. on 10 September. Cannons fired at the various forts, and the troops moved forward when a huge signal bonfire was lit. Despite the weeks of preparation, things did not go entirely to plan. First, a Parliamentarian deserter informed the Royalists of the attack plan. Second, the assault on the southern walls ended in a debacle when the ladders of the besiegers were found to be too short for the task. Third, a high tide blocked the planned amphibious attack on the Water Fort.

The attack on the eastern side went much better, the defensive positions were broken through, and a number of cannons were captured. Bridges were hastily built over the ditches to provide easier access for the next wave of attackers. The Royalists were thus obliged to withdraw within the city's old medieval walls. It was a similar story elsewhere as a number of forts and gates were captured. Other forts, notably Prior's Hill Fort, were fiercely defended, and no quarter was given. The city's main castle also held out and peppered the attackers with cannon fire, but as the sun rose, Fairfax had control of nearly all of Bristol's outer defences. Both sides were now kept busy putting out the many fires that threatened to overwhelm the city.

Rupert knew that the inner part of the city could not be held indefinitely and any prolonging of the siege could only bring more misery, although some of the Royalist commanders were still intent on fighting as long as they held the castle. At 9 a.m., the prince requested a truce while talks were held. Rupert decided to surrender on not unfavourable terms: he was allowed to lead the Royalist army, colours intact, to the safety of Oxford. Rupert claimed that he had never had either the men or the ammunition to properly defend the city (although it later transpired that he had had 130 barrels of gunpowder at his disposal).

Aftermath

When King Charles was informed of the disaster, he was outraged and considered Rupert's surrender a great dishonour. The king complained: "…for what is to be done after one that is so near me as you are, both in blood and friendship, submits himself to so mean an action?" (Bennett, 72). Rupert was stripped of his titles and offices. The prince beseeched his uncle to give him an audience so that he could explain his actions and the military necessities that had given him little choice in the affair. Charles refused, but Rupert forced his way to Newark and demanded a court-martial enquiry, confident it would absolve him of any charges of cowardice or disloyalty to the king. A court-martial was convened, and it did find the prince not guilty, but relations between king and nephew were soured forever, even if there was a token reconciliation.

The war, meanwhile, was effectively ended in military terms with the defeat of the Royalist army led by Lord Astley (1579-1651) at Stow-on-the-Wold on 21 March 1646. King Charles fled his capital Oxford in disguise on 27 April and sought refuge in Scotland. Bristol, meanwhile, continued to thrive as a port, although its fortifications were reduced in 1647 and Fort Royal was demolished in 1655.