By the time he led his invasions of Britain, Julius Caesar (100-44 BCE) was already an experienced politician and successful military commander. As a member of a patrician family which claimed a pedigree reaching back even earlier than the foundation of the city of Rome, Caesar seemed destined to climb the political career ladder.

In 63 BCE, he was elected praetor, a senior role in Roman politics which also qualified him for a military command there. After a year in that post at Rome, he began a term as governor of the Roman province of Spain and won his first military campaign. Provincial governors, who managed military and civil affairs in Roman provinces, were often appointed for around three or four years. Returning to Rome in 60 BCE, he was made consul; following his year in this senior office he was appointed governor of Cisalpine Gaul and Illyricum. Transalpine Gaul was later added to his command. In 58 BCE, he travelled to Gaul and led Rome into a major eight-year war, enabling him to demonstrate his considerable prowess as a general.

During the first three years of this campaign, Caesar made extensive conquests across central and northern Gaul. The Gauls were subdivided into many independent peoples who did not form politically unified groups but were loose associations united under a single leader. Some of these peoples fought Caesar while others submitted, and indeed the division of the Gallic opposition was a significant reason for Caesar's swift successes. He led campaigns against those who opposed him, defeating and subduing them individually and driving back some Germanic groups to their lands to the north of the Rhine. Then, late in the fourth season of campaigning, he decided to invade Britain.

The dispatches Caesar sent back to Rome conveyed news of these campaigns to his peers and were later summarized in the eight books of his famous work The Gallic War (De Bello Gallico). Each book addressed the campaigns of a single year, and his account of his two invasions of Britain is included in books 4 and 5.

Motives for Invading

Sailing over the Channel to Britain was the most challenging undertaking Caesar and his legions had attempted. Why did he wish to campaign in Britain? As mentioned earlier, he was attracted by the idea of emulating the deeds of Hercules and Alexander, but he had already defeated many peoples in Gaul. Why was travelling to Britain so important to him? The attraction of invasion arose from the very lack of information about Britain available at Rome.

Caesar provided a practical reason for wishing to force the submission of the Britons, observing that his enemies had received reinforcements from the island in almost all of the wars he had fought in Gaul. He described one of these occasions, observing that the Britons, together with Gallic allies, had provided assistance to the Veneti, a coastal people of north-western Gaul, with their resistance to Rome in the winter of 57-56 BCE. Indeed, Caesar's naval campaign against the Veneti may provide a clue to the motivation that drove him to invade Britain the following year. The Veneti, Caesar explained, excelled in the nautical skills they had learned by living beside a 'fierce and open sea' with only a few 'exposed landing places'. They used their large fleet to dominate this coast by exacting tolls on those who travelled on the sea and traded with Britain.

Rome had long been renowned for its land-based legionary forces, which had been the core of the successes that had built the empire. In contrast to the Veneti, as Caesar remarked, his soldiers had little skill with ships, while their knowledge of the waters, landing places, and islands of this coast was very limited. These comments were somewhat disingenuous, however, in view of the experience that Roman troops had gained as a result of earlier naval campaigns, including Pompey the Great's (106-48 BCE) defeat of the pirates in the Mediterranean ten years before.

Challenges

Caesar titled these Atlantic waters 'the great unbounded Ocean', observing that sailing them was a distinctly different experience from navigating the landlocked Mediterranean Sea. The name 'Mediterranean' is derived from the Latin mediterraneus, meaning "in land" or "in (the middle of the) land", but the Romans, like the Greeks before them, called it simply mare nostrum, "our sea", for Roman commanders had defeated the peoples who lived around it. A naval campaign on the fierce open waters of the Atlantic was a far more challenging undertaking than sailing the Mediterranean. Caesar's observations on the nature of the 'unbounded Ocean' described the practical difficulties he faced in mounting a naval campaign. He may have been aware of the accounts of Phoenician and Carthaginian explorers, and that of Pytheas the Greek, who, in previous centuries, was said to have sailed through the Pillars of Hercules. These writings addressed the extreme difficulty of navigating the Atlantic, with its dense fogs, sluggish waters, severe storms, and giant sea creatures.

Caesar ordered the construction of a substantial fleet for campaigning against the Veneti and laid siege to their coastal strongholds (oppida), while the Roman ships, commanded by Decimus Brutus, won a battle at sea in 56 BCE. This maritime victory may have emboldened Caesar to undertake the challenging task of crossing Ocean to campaign in Britain. He may have thought the voyage would also provide an opportunity to reconnoitre the island and its people: he observed that it would be 'a great advantage' to land on the island and to observe what kind of people lived there and the nature of their territories, harbours, and approaches.

The Gauls he had interviewed apparently had claimed to know little about Britain. Even the traders refused to provide any detailed knowledge of the lands and peoples that lay beyond the coastline opposite Gaul. Caesar intended to supplement Roman knowledge by obtaining information about the island and its people and by forcing their leaders to submit to him. He profited from the bribes he received and the booty he collected from the peoples he conquered: his campaigns were partly motivated by avarice. He must have wondered about the potential for plunder in these otherworldly lands. Moreover, the sons of other elite families at Rome flocked to serve on Caesar's staff, and booty forfeited from defeated enemies made fortunes for many.

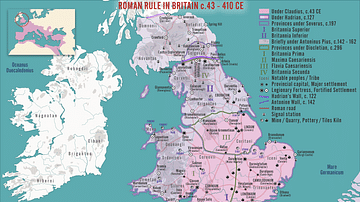

Claudius' Conquest

Roman interest in Britain for the following century was limited to diplomacy, as the emperors Augustus (r. 27 BCE to 14 CE) and Tiberius (r. 14-37 CE) aimed to keep peace by making alliances with several friendly kings in south-eastern Britain. Caligula (r. 37-41 CE)planned an invasion in 40 CE but failed to follow this though, and it was left for the emperor Claudius (r. 41-54 CE) to command the conquest of Britain three years later following the murder of his predecessor. Southern and central Britain was then conquered by a series of provincial governors appointed by Claudius' successors Nero (r. 54-68 CE), Vespasian (r. 69-79 CE) and Domitian (81-96 CE). By 84 CE, the governor Agricola won a battle in northern Britain at an unlocated site called Mons Graupius. It looked for a while as if the whole mainland of Britain would be conquered by Rome, although eventually the frontier was withdrawn to central Britain, where Hadrian's Wall was constructed in the early 120s CE. These conquests were motivated by the resources that could be obtained, particularly minerals and slaves, but also by the status of Britain as an exotic and unworldly place set in Ocean.