Musketeers played a vital role in the battles and sieges of the English Civil Wars (1642-1651). As the war dragged on, weapons became lighter and more accurate, and the musketeers became more capable of effective battlefield manoeuvres. Volley-fire, where alternate ranks of musketeers provided a continuous barrage of lead bullets, could be extremely effective, and the success of the musket brought about the decline of other types of weapons as warfare, now dominated by gunpowder, became much louder and deadlier than ever before.

Civil War Armies

Infantry regiments formed at least half of a total fighting force during the Civil War. The Royalist army was made up of disparate groups led by particular noblemen, and their strength and composition varied widely. On the other side, the New Model Army of the Parliamentarians became more standardised as the war went on. A full-strength infantry regiment was composed of around 1,200 men organized into ten companies of various sizes depending on the seniority of the officer commanding them. However, regiments were rarely at full strength, and a force of 500-700 men was more typical. Companies could be joined to create divisions, a rather loose classification that depended on the tactical necessities of the engagement.

Infantry were armed with either pikes (5.5-metre/18-foot long poles topped with a long spike) or muskets. The typical ratio was one pikeman to three musketeers, but this varied throughout the war. and Royalist armies often had a higher proportion of musketeers as they were considered very effective troops. In battle, the infantry companies were arranged into as many as six rows with the musketeers on the flanks and the pikemen in the centre of each group. The most experienced fighting men were placed at the front, and it was the job of the pikemen to protect the musketeers, particularly from enemy cavalry. Sergeants were responsible for keeping good order and ensuring everyone had a ready supply of powder and ammunition. Troop movements in battle were dictated by the use of flags and the sound of drummers, who had a repertoire of at least eight different calls.

Interestingly, there were still some reservations over the dishonour of being able to injure an enemy from afar, and so a pike was still thought of as a more honourable weapon than a musket. Consequently, it was the pikemen who carried a regiment's colours and not the musketeers.

Musketeers were involved in both the attacking and defending sides during the many sieges of the war. Another function of musketeers was to protect the unarmed men who operated cannons during a battle. Artillery units typically had two companies of musketeers alongside in case the enemy overran their position. These musketeers usually had the latest flintlock weapons (see below) to avoid using the older slow-burning matches that could set off the nearby stores of gunpowder. One episode is recorded of a matchlock musketeer at the battle of Edgehill in October 1642:

A careless soldier in fetching powder where a magazine was, clapped his hand carelessly into a barrel of powder with his match between his fingers, whereby much powder was blown up and many killed.

(quoted in Gaunt, 33)

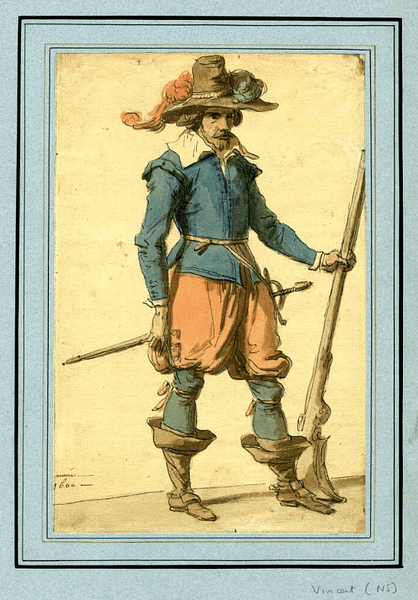

Clothing

Musketeers did not usually wear any armour. They wore jackets and baggy breeches which were tied just below the knee. A double layer of stockings was worn for the lower legs, and shoes were made of leather and closed with laces or a buckle. Musketeers could wear a simple close-fitting cap or even a steel helmet, but the most common headgear came to be a high, wide-brimmed felt hat which was typically given a personal touch by adding feathers. Coloured sashes, ribbons, and even sprigs of foliage were worn as 'field signs'. Additionally, the coloured lining of one's coat was exposed by folding back the cuffs. These marks of identification were necessary since homogenous uniforms were rarely issued. Clothing and equipment were issued by the respective authorities, but the costs were deducted from the musketeer's pay.

Equipment

Musketeers had to carry quite a bit of equipment besides the heavy musket itself. They carried a ramrod to load the barrel of the musket, to clean it, and, with a small screw attachment added, to remove a charge that had misfired. They had 'Twelve Apostles' (12 prepared cartridges) in a leather bandolier belt slung across their chest. From this belt hung a powder flask, a priming flask, a pouch of bullets, and spare matches. This equipment had to be kept dry so battles in wet weather greatly reduced the effectiveness of musketeers. Not entirely successful remedies to wet-weather conditions were to have a large leather flap hang over the front of the bandolier belt, to keep powder in a box hung around the waist, to place a metal cap over the lit end of the match, and to keep spare matches under one's hat.

It was, of course, dangerous to carry so much gunpowder around one's body in the middle of a battle. As one commander, Lord Orrery, noted regarding bandoliers: "And when they take fire they commonly wound and often kill him who wears them, for likely if one bandolier takes fire, all the rest do in that collar…" (Asquith, 33).

Muskets

The Royalists received many arms from Bristol; armourers in the city produced some 200 muskets and bandoliers each week through 1644. The Parliamentarians benefited from the armouries in the Tower of London and at Woolwich and Greenwich, amongst others. Weapons were also imported from Continental Europe, particularly the Netherlands. Naturally, weapons were also captured from the losing side after a battle.

Matchlock Muskets

Musketeers used the matchlock musket, a firearm with a barrel up to 122 cm (48 in) in length at the start of the war and progressively shorter in design over time. The weapon was heavy and had to be supported with a V-topped pole, although this became unnecessary with new lighter designs later in the war. The flame that set off the gunpowder to fire the bullet was provided by a slow-burning match, essentially a piece of hemp cord that had been boiled in vinegar, wine, or a solution containing saltpetre. The match was placed in a 'serpent' - an ornate metal bracket - which was lowered onto the priming pan when the trigger was pulled back. The priming pan had a small cover, which the musketeer flipped open when ready to fire. This pan contained the priming powder (fine-grained gunpowder) which, when lit, set off the main charge of gunpowder through a small hole in the side of the weapon. The match had to be kept lit during a battle, which presented several problems. The most obvious problem was what to do if the match went out, either through neglect or wet weather. A second problem was the risk of having a constantly lit cord near where there was lots of gunpowder. A third problem was that, at night, a lit match revealed the whereabouts of a musketeer to the enemy.

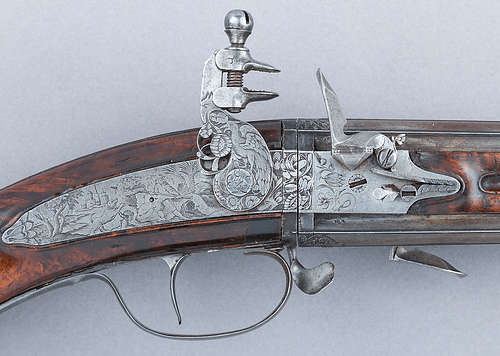

Flintlock Muskets

The flintlock (aka firelock) musket was more expensive to produce, but its advantages meant it eventually came to outnumber matchlocks. The flintlock did not need a lit match but instead lit the powder by creating a spark when the trigger caused a lever with flint attached to it to strike against a piece of metal in the breech. The flint mechanism was more prone to breaking than the simpler matchlock mechanism, and it was not quite as reliable in terms of igniting the powder – sometimes the trigger had to be pulled twice. Nevertheless, the flintlock was much safer to use and saved on operating costs as matchlock musketeers went through a prodigious amount of matches each battle.

Only some musketeers carried swords, and their style depended on individual taste. If a musketeer ran out of ammunition or found himself with no time to reload before the enemy was on top of him, they most often used their rifle as a club, as was documented in the Battle of Naseby in June 1645 and elsewhere.

Bullets & Accuracy

Loading and firing either type of musket was a slow business, taking up to one minute even for a well-trained musketeer in the heat and drama of battle conditions. A quantity of gunpowder (in ready-measured paper packets that were ripped open when required), bullet, and wadding (usually the same paper the powder had been wrapped in) were rammed down the barrel using a thin metal rod. Some musketeers kept spare bullets in their mouths to save a few precious seconds. The priming powder was poured into the lock mechanism, and the match or flint set off the powder with a cloud of smoke and fired the bullet. As the war progressed, cartridges became a more common sight. These were ready-made pieces of rolled paper that enclosed both a bullet and a small quantity of powder. The musketeer thus saved some more vital seconds by being able to ram powder, ball, and wadding down the barrel all at the same time.

A musket bullet was spherical, made of lead, and quite heavy at 28 grammes or 1 oz. It could easily smash through bone, but its very heaviness offered a significant wind resistance, reducing the firing range. Another problem was the lack of uniformity in musket designs so that often bullets were too big or too small for the barrel of a particular weapon. In the former case, musketeers had to cut the ball to size with a knife or their teeth, and in the latter case, distance and accuracy were compromised.

A musket could fire a correct-size bullet up to 365 metres (400 yards) but was only effective at a much shorter range than that. If a target was further than 90 metres (100 yards) away, the shooter was firing more in hope. In addition, the prodigious amount of smoke a single shot released meant that the battlefield quickly became obscured, further reducing the effective range of the weapon.

Finally, there was an early form of sniper in both armies. Armed with more accurate hunting guns (then called 'fowling pieces') with longer and rifled barrels, a small team of such sharp-shooters could be tasked with, for example, picking off a number of the enemy operating artillery pieces.

Formations & Tactics

Due to their poor accuracy, muskets were most effective as volley fire, when a line of usually six musketeers all fired at once. While this line turned to the rear and reloaded, a second line would fire. Operating with up to eight ranks of musketeers, a commander could present a reasonably sustained fire at the enemy. A variation on this tactic has long been credited to King Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden (r. 1611-1632). Gustavus had his musketeers fire in two or three ranks at once with the front rank kneeling, those behind crouching, and the back line standing.

Spanish and Dutch armies were another source of development in warfare, particularly higher mobility and more thorough and professional training. This training was provided not only by instructors but also via illustrated manuals which showed all the different postures the musketeer should adopt as they went through the motions of preparing and firing their weapon. These ideas came to England via printed works and mercenaries who had fought in the various conflicts in Continental Europe.

Manoeuvres during battle required a great deal of training, both to improve the time needed to reload and to choreograph which rank fired when. Although many 'postures' were learnt in training, in actual battle the orders were but three: "Make Ready. Present. Give fire." As volley-fire need not be so accurate as a single shot, musketeers could in this way fire upon an enemy up to 180 metres (200 yards) away, doubling the distance of their effectiveness. Another significant advantage of operating in formations was that it greatly reduced the rate of casualties.

Volley-fire could be devastating, but it did not always go to plan. During the attack on Basing House in November 1643, a body of inexperienced musketeers managed to all fire at the same time, and so the front rows were cut down by their colleagues. There are, too, several recorded incidents where senior officers were wounded by a musket ball from their own side. In the hullabaloo of battle with its noise, smoke, chaotic troop movements, and unclear terrain of ditches and hedgerows, friendly fire was a real and ever-present danger as gunpowder weapons came to dominate the battlefield.