Huldrych Zwingli (l. 1484-1531) died in the second of the Kappel Wars in 1531, a conflict between Catholic and Protestant forces. Afterwards, two accounts of his death emerged – one Catholic and one Protestant – differing in detail and notable as examples of the schism between the two groups caused by Zwingli's reformation.

Zwingli, leader of the Protestant Reformation in Switzerland at the time, had instigated the First Kappel War and agreed to a blockade of Catholic provinces between 1529-1531 in an effort to forcibly convert the Catholic cantons (provinces) to his Reformed vision of Christianity. To the Protestants of Zürich – and then other cantons that converted to his faith – he was a God-inspired hero and champion of Christian truth while, to the Catholics, he was a dangerous heretic. When he was killed in the Second Kappel War, a Catholic victory, the differing faiths were succinctly summarized in the two accounts of his death.

The Catholic account was written by the playwright and mercenary Johannes Salat (d. c. 1561) who was present at both the First and Second Kappel War and could easily have been an eyewitness to the event. The Protestant version was the work of Zwingli's admirer, and successor to his position in Zürich, Heinrich Bullinger (l. 1504-1575), who was still in his hometown of Bremgarten in 1531 and could not have been a witness to the events he describes.

After the Second War of Kappel, Swiss cantons were given the freedom to choose Catholicism or Protestantism and kept an uneasy peace which did nothing to address the animosity each side felt for the other. The two accounts of Zwingli's death are among the best documents of the time expressing how each side understood their own beliefs and how they viewed the other.

Kappel Wars

The Kappel Wars were the result of increasing tension between Protestant and Catholic Christians in Switzerland, which had been growing since Zwingli began preaching for the reform of the Church in 1519. The Protestant Reformation, though it had earlier advocates, began in 1517 in Germany through the efforts of the priest and theologian Martin Luther (l. 1483-1546), and by 1519, Zwingli was rejecting church liturgy and calling for reform in Switzerland. In 1522, Zwingli challenged the traditional practice of Lent, and in 1523, in a public disputation, Zwingli's 67 Articles expressed the tenets of his faith and denounced the Church's policies as unbiblical.

Zürich embraced Zwingli's vision and, by 1529, a number of other cantons had as well. Five Catholic cantons refused to renounce their faith, however, and Zwingli, formerly a pacifist, advocated for war to change their minds. He believed that a united Protestant Switzerland would represent God's true will for the Church on earth and that Catholics who refused to recognize this were not only standing against Zwingli and his teachings but against God himself. Accordingly, he mobilized the Protestant cantons to attack the Catholics in the First Kappel War of 1529.

This engagement ended before it could begin when a delegation from the Protestant canton of Bern negotiated a peace. Although the First Peace of Kappel held off hostilities, it did nothing to address the underlying issues and, further, was not clear on certain points, notably how Catholic cantons were to receive – or allow – Protestant preachers in their regions. To speed the Catholics' conversion, Zwingli called for war a second time but was forced to agree to the less severe measure of a blockade of the Catholic cantons in May 1531.

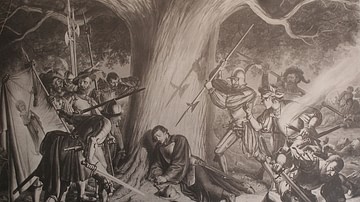

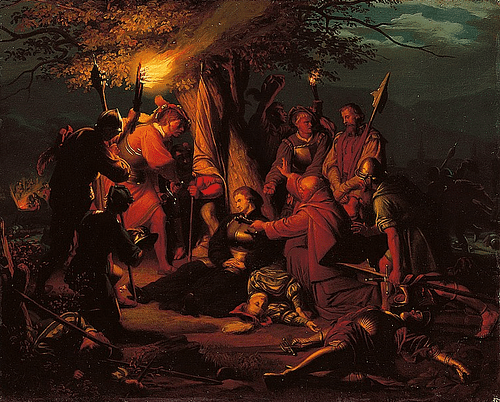

Although the blockade was lifted later, the Catholics felt they needed to respond before Zwingli suggested a further attempt, and so they marched on Zürich in October 1531, catching the city by surprise. The Protestants were badly outnumbered, poorly mobilized, and lacked strong leadership, leading to their defeat in under an hour. Zwingli was among the 500 casualties of the Protestant forces.

Salat & Bullinger

Johannes Salat was a part-time playwright and historian, a ropemaker by trade, who, like many men in Switzerland at the time, hired himself out as a mercenary to various causes through the mercenary pensioner system. These 'pensioners', as they were sometimes called, had no allegiance to the king or prince they were fighting for, they were just paid soldiers, but this was not the case with the Kappel Wars. The Catholic troops mobilized for both battles understood they were fighting for their freedom to practice their religion as they always had and, further, believed they had God on their side since they understood the Catholic Church as the true representative of divine will on earth.

Salat had attacked Zwingli in writing prior to 1531 and would later attack Bullinger and other Protestants. To Salat, and Catholics generally, these men were not heroes to be admired but heretics who were anti-Christ and anti-Christian and whose works sought only to destroy God's Church. The Church had been understood for centuries as the sole spiritual authority, ordained by Jesus Christ himself and founded by Saint Peter, and teachings of the medieval Church informed European society completely. Breaking from the Church was understood as not only an affront to one's family, community, and ancestors but also a breach of loyalty to one's prince and an act of rebellion against God.

Once the Reformation movement was set in motion, long-standing practices, values, and even the social structure were challenged, discarded, and reimagined according to a new paradigm which many rejected as anti-Christian. Scholar Randolph C. Head comments:

In this context, many medieval assumptions about hierarchy, orthodoxy, and authority no longer applied, it seemed to many contemporaries, even as the realities of religious difference and coexistence raised new problems and possibilities…Most challenging, perhaps, were the challenges to authority that the evangelical movement's success brought to the fore. Thus, Zwingli and his peers justified their claims to speak sacred truth in part by appealing to the authority of conscience, of texts, and of communities; in rejecting the authority of the existing church to speak definitively, they expanded on other existing ideas to justify their new movements. (Rublack, 179)

Zwingli, like Luther, preached the Bible as the sole spiritual authority and denounced the Church as a self-serving entity more engaged in worldly affairs than the cause of spiritual salvation. Zwingli's insistence on the primacy of individual interpretation of the Bible, and rejection of any teachings or practices not supported by scripture, appealed to many clerics and theologians and, among them, was the young Lutheran minister Heinrich Bullinger.

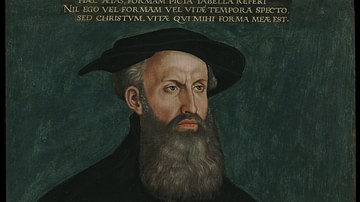

Bullinger was a scholar and theologian who was first influenced by Luther's efforts and the works of Philip Melanchthon (l. 1497-1560) and then by Zwingli. He accompanied Zwingli to the Bern Disputation in 1528 and preached the Reformed vision at his church in Bremgarten, Aargau region, challenging the Church's policy on icons. He continued in his position as a parish priest until after the Second War of Kappel when Bremgarten became Catholic, and he moved to Zürich, taking over Zwingli's position as people's priest at the Grossmünster (Great Church) in the city.

The Texts

As noted, Salat was a participant in both Kappel Wars while Bullinger was not. Even so, it is not the details of Zwingli's death alone that give the documents their value but what the accounts reveal about how Catholics and Protestants understood themselves and each other at the time. Salat's version depicts Zwingli as a vile troublemaker who got what he deserved and was justly killed by divine will, while to Bullinger, Zwingli was a representative of the 'true faith of Christ' who was poorly treated by his killers and later maligned by those who either never knew him or who blamed him for inciting the wars.

The following texts are taken from A Reformation Reader: Primary Texts with Introductions by Denis R. Janz. The passages have been broken into separate paragraphs and some punctuation modified for clarity.

Salat's Catholic Account

Zwingli was found in the front line where the Zurich force had been drawn up. He was lying on his face, which had not been scratched or wounded. A Catholic soldier, not knowing who he was, turned him over and shook him so that he might have air and be able to breathe. He opened his eyes and looked round. Then he was asked if he wished to confess his sins. He shook his head and indicated that he did not wish to do so. Thereupon another warrior standing by struck Zwingli a fatal blow on the neck under the chin with his broadsword.

Then a number of men arrived who had known Zwingli when he was alive, looked at him and sought for identification marks on his body. They found that it really was Zwingli. Then they had much to say, rejoicing in his death and calling him a good many entirely unsuitable names. They added their repeated thanks to almighty God whose vengeance lay there in the blood of the miscreant who had been the true founder, originator, creator, and initiator of all their evils, calamities, and alarms. Even so, God had graciously allowed him to die in the presence of, and surrounded by, good, honorable, men, perhaps because he had once been a priest. It would not have been remarkable if there had been more devils by him at his end than there were soldiers in the field.

For the whole evening, more and more Catholics came to look at the dead body of one who had been responsible for bringing more discontent, disorder, trouble, need, and anxiety than had all the princes, lords, peoples, and cities. He now lay there given by God's instrumentality into their hands, and he had paid the price for his wickedness. There, at last, was the representative of all the Confederates, and (by the grace of God) all his schemes perished with him. (198)

Bullinger's Protestant Account

On the battlefield, not far from the line of attack, Mr. Ulrich Zwingli lay under the dead and wounded. While men were looting…he was still alive, lying on his back, with his hands together as if he was praying, and his eyes looking upwards to heaven. So, some approached who did not know him and asked him, since he was so weak and close to death (for he had fallen in combat and was stricken with a mortal wound), whether a priest should be fetched to hear his confession. Thereat, Zwingli shook his head, said nothing, and looked up to heaven.

Later, they told him that if was no longer able to speak or confess, he should yet have the mother of God in his heart and call on the beloved saints to plead to God for grace on his behalf. Again, Zwingli shook his head and continued gazing straight up to heaven. At this the Catholics grew impatient, cursed him, and said that he was one of the obstinate cantankerous heretics and should get what he deserved. Then Captain Fockinger of Unterwalden appeared and, in exasperation, drew his sword and gave Zwingli a thrust from which he at once died.

So the renowned Mr. Ulrich Zwingli, true minister and servant of the churches of Zurich, was found wounded on the battlefield along with his flock (with whom he remained until his death). There, because of his confession of the true faith in Christ, our only savior, the mediator and advocate of all believers, he was killed by a captain who was a pensioner, one of those against whom he had always preached so eloquently…

The crowd then [12 October] spread it abroad throughout the camp that anyone who wanted to denounce Zwingli as a heretic and betrayer of a pious confederation should come onto the battlefield. There, with great contempt, they set up a court of injustice on Zwingli which decided that his body should be quartered and the portions burned. All this was carried into effect by the executioner from Lucerne with abundance of abuse; among other things, he said that although some had asserted that Zwingli was a sick man, he had in fact never seen a more healthy-looking body.

They threw into the fire the entrails of some pigs that had been slaughtered the previous night, and then they turned over the embers so that the pig's offal was mixed with Zwingli's ashes. This was done close to the high road to Scheuren. Verdicts on Zwingli from scholars and ignorant alike were varied. All those who knew him were constant in their praises. Even so, there were still more who were critical either because they really did not know him or, if they had known him a little, were determined to show their resentment and spoke ill of him. (199)

Conclusion

After the Second Kappel War, Salat wrote tracts and pamphlets attacking Bullinger, and the latter replied in kind. Little is known of Salat's life after 1540, and even his date of death has been challenged, but Bullinger's life was well documented as he became Zwingli's successor, defending him against detractors who blamed him for the costly war. The source of Bullinger's account of Zwingli's death is unknown, but the work is in keeping with his later defense of Zwingli as a visionary called by God to illuminate the people in a time of darkness. This darkness, of course, was considered the light of salvation by Catholics, and so compromise between the two visions of Christianity was difficult, if not impossible.

Bullinger adopted a more moderate stance than Zwingli, wrote the Helvetic Confessions, which served the Reformed Church of Switzerland Zwingli had founded as well as others elsewhere, and he served as a bridge between Zwingli's radical reform efforts and the fully developed theology of John Calvin (l.1509-1564), who would complete the Swiss Reformation and systematize the Reformation as a whole. Even so, Bullinger's moderation and Calvin's theological justification did nothing to reconcile the differing Christian sects.

Salat's account represents the view of the traditionalists who rejected the Reformation's call for change and viewed Zwingli as a coworker with Satan, while Bullinger's account presents him as a martyr who died in service of the true faith. These opposing views of reformers like Zwingli, as well as of the respective visions of Christianity, would continue long after the Second Kappel War and, in part, inform the Thirty Years' War (1618-1648), one of the most destructive and costly conflicts in European history.