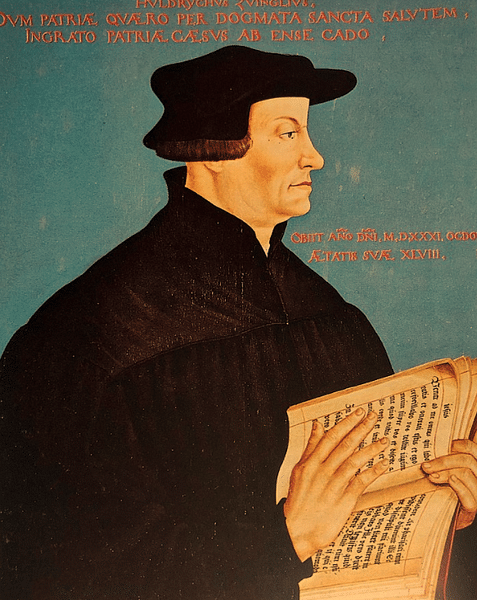

Although Huldrych Zwingli (l. 1483-1531) began his Reformation efforts in Zürich in 1519, his first break with the Church came in 1522 when he defended a group of citizens who had broken the Lenten fast by eating sausages. The event, known as the Sausage Episode or Affair of the Sausage, marks the beginning of the Protestant Reformation in Switzerland.

The event took place on the first Sunday of Lent, 1522, when one of Zwingli's parishioners, the printer Christoph Froschauer, invited twelve friends (including Zwingli) to dinner and served sausage in defiance of the Church's prohibition on eating meat during Lent. Zwingli himself did not partake of the sausage but is thought to have given his tacit approval by his presence. When word spread of the sausage dinner, Froschauer was arrested and the others denounced until Zwingli defended them in his sermon, Regarding the Choice and Freedom of Foods in which he argued that fasting during Lent – or at any other time – was unbiblical. He then explained the reasons for his sermon in his On Rejecting Lent and Protecting Christian Liberty from Man-Made Obligations that same year, a summary of the longer sermon.

The Bishop of Constance was outraged by the sermon and demanded Zwingli be removed as the people's priest of the Grossmünster (Great Church), but the city council, instead, allowed him to present his arguments and arranged a debate between him and a Catholic delegation. The result was the First Disputation of 1523 during which Zwingli's 67 Articles were delivered, establishing his Reformed platform while charging the Church with corruption and anti-Christian policies unsupported by scripture. After the Second Disputation that same year, Zwingli was firmly established as the leader of the Protestant Reformation in Zürich and continued in that role until his advocacy for forcible conversion of Catholics by war resulted in his death during the Second Kappel War in 1531.

Initial Rebellion

Zwingli was appointed as people's priest of the Grossmünster of Zürich in 1519, over objections from some of the more conservative clerics, as he had already shown what they considered 'unruly tendencies' in satirizing church policy in writing. Martin Luther's 95 Theses had already sparked Reformation in Germany beginning in 1517, and by 1519, they had been translated into the vernacular and widely published. Martin Luther (l. 1483-1546) was a priest and theologian in good standing prior to his criticisms of church policy, and conservative clergy were uneasy over appointing someone who might be sympathetic to reform to the most influential ecclesiastical post in Zürich.

Their concerns turned out to be well-founded, since as soon as he took to the pulpit at Grossmünster, he discarded the traditional liturgy of the Church and began reading from, interpreting, and commenting on the Gospel of Matthew in direct defiance of church policy. As the people's priest, Zwingli served not only as a pastor but also as a mediator between the people and the city council, and so the position offered one the possibility of ecclesiastical, social, and political influence. In 1521, again over opposition from conservatives, Zwingli was made a canon (magistrate) and citizen of Zürich, and by this time, his powerful oratory and clear defiance of papal authority had made him a popular figure among the people and well-respected by the council.

Martin Luther had openly defied the Church at the Diet of Worms in April 1521, and the Edict of Worms had condemned him as an outlaw and heretic, but the city council at Zürich refused to publish the edict as they were sympathetic to his cause. Zwingli's steady refusal to comply with church policy was also quietly approved of until the Affair of the Sausage brought wider attention to his activities and they were forced to take sides publicly.

The Affair of the Sausage

Luther's Reformation in Germany encouraged others to question the Church's authority elsewhere, and Zwingli certainly was already fanning the sparks of the Reformed movement in Germany prior to Lent in 1522. Many modern-day scholars and historians, in fact, believe Zwingli orchestrated the Affair of the Sausage and news of the dinner to the public to allow him a public forum through which he could confront the Church with what he saw as its corrupt practices. Others believe the event was spontaneous and Zwingli simply capitalized on the resultant scandal. Scholar Hughes Oliphant Old comments:

Fasting had come to be the touchstone of a serious devotional life. It was at the heart of the liturgical calendar. There were two long fasting seasons of the year, Advent and Lent; then there were Friday fasts…Apparently, the revolt against the fasting laws arose spontaneously among the citizens of Zurich. It was not a planned program of reform. During Lent of 1522, several prominent citizens of Zurich, including the distinguished publisher Christoph Froschauer, publicly broke the Lenten fast. There was a hearing over the matter, and the defendants appealed to Zwingli's preaching to justify themselves. There was consideration of the matter throughout the town, and Zwingli took to the pulpit to assure his congregation that Christians living under grace were not bound by laws regarding which foods were permitted and which were not permitted. That had been characteristic of the Law of Moses, not the gospel of Christ. Since Froschauer had been particularly involved, it is not surprising that he published Zwingli's sermon. (51)

After Zwingli's defense of Froschauer and the others, the city council decided against pressing charges in the matter. According to scholar Diarmaid MacCulloch (among others), Froschauer, Zwingli, and the other participants at the dinner (including the priest Leo Judd, who would become one of Zwingli's most vocal supporters) fully intended news of the sausage dinner to go public to provide Zwingli with the opportunity to denounce fasting during Lent as well as Lent itself. If so (and this does seem probable), their plan worked perfectly. Froschauer was freed, none of the others were prosecuted, and Zwingli delivered one of his most powerful sermons.

Text of On Rejecting Lent

Afterwards, in clarifying his reasons for the sermon and to summarize it, he delivered his sermon On Rejecting Lent and Protecting Christian Liberty from Man-Made Obligations. In this text, he first compares his parishioners to the Israelites led out of bondage in the Book of Exodus who have been freed, moves from that comparison to touch on the 'scandal' of the sausage dinner, and explains why the participants did nothing wrong but still required his defense as their pastor. He concludes with his assertion that he has only adhered to scripture, thereby advancing his claim that his vision of Christianity is more authentic than that of the Roman Catholic Church.

The following text is taken from The Latin Works and the Correspondence of Huldrych Zwingli: Together with Selections from His German Works by Samuel Macauley Jackson, translated by Henry Preble, pp. 71-73:

DEARLY Beloved in God, after you have heard so eagerly the Gospel and the teachings of the holy Apostles, now for the fourth year, teachings which Almighty God has been merciful enough to publish to you through my weak efforts, the majority of you, thank God, have been greatly fired with the love of God and of your neighbor. You have also begun faithfully to embrace and to take unto yourselves the teachings of the Gospel and the liberty which they give, so that after you have tried and tasted the sweetness of the heavenly bread by which man lives, no other food has since been able to please you. And, as when the children of Israel were led out of Egypt, at first impatient and unaccustomed to the hard journey, they sometimes in vexation wished themselves back in Egypt, with the food left there, such as garlic, onions, leeks, and flesh-pots, they still entirely forgot such complaints when they had come into the promised land and had tasted its luscious fruits: thus also some among us leapt and jumped unseemly at the first spurring—as still some do now, who like a horse neither are able nor ought to rid themselves of the spur of the Gospel;—still, in time they have become so tractable and so accustomed to the salt and good fruit of the Gospel, which they find abundantly in it, that they not only avoid the former darkness, labor, food, and yoke of Egypt, but also are vexed with all brothers, that is, Christians, wherever they do not venture to make free use of Christian liberty.

And in order to show this, some have issued German poems, some have entered into friendly talks and discussions in public rooms and at gatherings; some now at last during this fast—and it was their opinion that no one else could be offended by it—at home, and when they were together, have eaten meat, eggs, cheese, and other food hitherto unused in fasts. But this opinion of theirs was wrong; for some were offended, and that, too, from simple good intentions; and others, not from love of God or of his commands (as far as I can judge), but that they might reject that which teaches and warns common men, and they might not agree with their opinions, acted as though they were injured and offended, in order that they might increase the discord. The third part of the hypocrites of a false spirit did the same, and secretly excited the civil authorities, saying that such things neither should nor would be allowed, that it would destroy the fasts, just as though they never could fast, if the poor laborer, at this time of spring, having to bear most heavily the burden and heat of the day, ate such food for the support of his body and on account of his work.

Indeed, all these have so troubled the matter and made it worse, that the honorable Council of our city was obliged to attend to the matter. And when the previously mentioned evangelically instructed people found that they were likely to be punished, it was their purpose to protect themselves by means of the Scriptures, which, however, not one of the Council had been wise enough to understand, so that he could accept or reject them. What should I do, as one to whom the care of souls and the Gospel have been entrusted, except search the Scriptures, particularly again, and bring them as a light into this darkness of error, so that no one, from ignorance or lack of recognition, injuring or attacking another come into great regret, especially since those who eat are not triflers or clowns, but honest folk and of good conscience?

Wherefore, it would stand very evil with me, that I, as a careless shepherd and one only for the sake of selfish gain, should treat the sheep entrusted to my care, so that I did not strengthen the weak and protect the strong. I have therefore made a sermon about the choice or difference of food, in which sermon nothing but the Holy Gospels and the teachings of the Apostles have been used, which greatly delighted the majority and emancipated them. But those, whose mind and conscience is defiled, as Paul says [Titus, 1:15], it only made mad. But since I have used only the above-mentioned Scriptures, and since those people cry out none the less unfairly, so loud that their cries are heard elsewhere, and since they that hear are vexed on account of their simplicity and ignorance of the matter, it seems to me to be necessary to explain the thing from the Scriptures, so that everyone depending on the Divine Scriptures may maintain himself against the enemies of the Scriptures.

Church's Response

The Bishop of Constance, Hugo von Hohenlandenberg (l. c. 1457-1532), was responsible for overseeing ecclesiastical affairs in a number of cantons (provinces) including Zürich and had been aware of Zwingli's activities for some time. He agreed with Zwingli's objection to the Church's policy on indulgences – writs sold by the Church to lessen one's time in purgatory – recognizing that they could not provide what they claimed to and were only a means of raising funds. He also seems to have turned a blind eye to Zwingli's rejection of liturgy and reading the Bible to the congregation during Sunday services.

When he heard of the sermon rejecting Lenten fasting, however, he was outraged and demanded Zwingli's dismissal. The Church had already learned from their experience with Martin Luther, however, that a heavy hand in dealing with reformers only increased their popular support, and so Hohenlandenberg requested the Zürich city council, which had power over ecclesiastical appointments, to send Zwingli away quietly.

The council refused and, instead, invited Hohenlandenberg to Zürich to debate the matter of Lenten fasting with Zwingli. The bishop refused to come himself but sent a delegation headed by the vicar general Johannes Fabri, instructing Fabri not to be drawn into a public debate on theology in front of unlearned laypeople where Zwingli would be able to make a good showing but to confront the renegade priest in private debate and steer him back to the fold of the Church.

Fabri, therefore, prepared himself for a private debate, but Zwingli, understanding his audience and the support he had from the council, wrote up his 67 Articles articulating the unbiblical nature of the Church and rejecting papal authority, the priesthood, the existence of purgatory, clerical celibacy, and addressing a number of other points in need of reform. Over 600 people attended the First Disputation in January 1523, and Fabri, held in check by the prohibition against discussing theology in public, could do little more than insist on the authority of the Church without providing support for his claims. Zwingli, on the other hand, delivered his 67 Articles eloquently, won the disputation, and was ordered by the council to continue preaching in accordance with scripture.

Conclusion

The Second Disputation, in October 1523, strengthened Zwingli's position in allowing individual churches to decide on policy such as the removal of icons, and, by spring 1524, many had moved away from traditional practices such as Easter observances and embraced Zwingli's teachings. Zwingli had been living with the widow Anna Reinhart for some time, and now, having proven clerical celibacy was unbiblical (as well as pointing out that most of the clergy lived secretly or openly with women and so they were hypocrites), he married her in a public ceremony. He also called for the dissolution of monastic orders and had the monasteries and convents of Zürich turned into hospitals, poor houses, and orphanages.

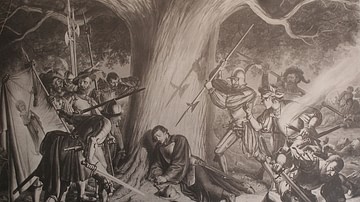

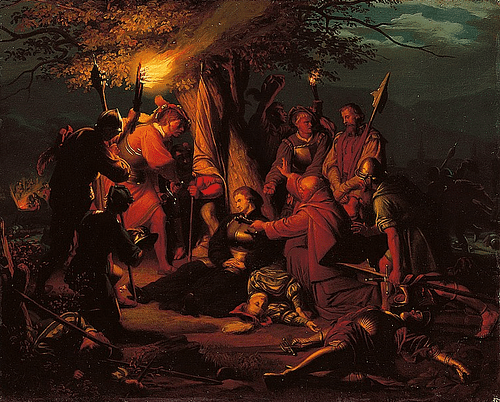

Zwingli's reforms continued through 1529, and as he gained more support, he became convinced that Switzerland, at that time a confederation of more or less independently operating provinces, should unite as a Protestant country, patterned after the Christian community in the biblical Book of Acts. When the Catholic provinces refused to accept his vision, he launched the Kappel Wars. The first war ended in an armistice before it could begin, but the peace did not address the animosity that had developed between Catholic and Protestant cantons.

The five Catholic cantons marched on Zürich in the Second Kappel War of 1531, and Zwingli was killed in battle as one of the 500 Protestant casualties. As Zwingli had encouraged the hostilities, he was blamed for the defeat, and his movement lost popular support until it was taken over by the more moderate Heinrich Bullinger (l. 1504-1575), who was able to stabilize and again popularize the Protestant interpretation of Christianity.

Although Zwingli failed in his goal of a Switzerland united under his vision, he succeeded in establishing the Reformation in the country, and his work was continued by Bullinger and other supporters until completed by John Calvin (l. 1509-1564). In the beginning, however, before he began to advocate forcible conversion, Zwingli had all the support he needed to develop his vision, and it all began with a simple sausage dinner during Lent.