Cavalry regiments were an essential component of both Royalist and Parliamentarian field armies during the English Civil Wars (1642-1651). Armed with a sword, carbine, and a brace of pistols, cavalry riders evolved to become fast, lightly-armoured shock troops whose job was to rout the opposition horse before turning on the infantry.

Charles I of England (r. 1625-1649) battled with Parliament over religious and financial issues and a bitter war ensued from 1642 to 1651. The 'Roundheads' (Parliamentarians) and 'Cavaliers' (Royalists) clashed in over 600 battles and sieges in a bloody and protracted conflict. There were a good number of large-scale battles and a great many skirmishes, with both types of confrontation involving cavalry units. Generally, it was the performance of the infantry that decided the victor, but the cavalry could be instrumental in gaining that victory. Such was the importance of cavalry in the Civil War that there were many military books written on the subject of how to train and manoeuvre cavalry troops for optimum results. The most consulted work of the period was John Caruso's Militarie Instructions for the Cavallerie, first published in 1632 and reprinted in 1644.

Weapons

Swords, the tried and tested weapon of warfare over centuries, were still wielded by 17th-century cavalry riders. The style was up to the individual, but horsemen tended to carry more durable broadswords with a double cutting edge. These swords typically had an iron hilt and steel blade. The hilt could include ornate metalwork to create a basket-like guard. One type of basket guard, known as a 'mortuary sword', had a cartouche with a representation of the head of King Charles. Early in the war, some riders still carried poleaxes, but these quickly gave way to firearms as the secondary weapon of choice.

The sword remained the primary weapon since a firearm could not be reloaded in battle conditions; it was also regarded as the more prestigious and honourable weapon, particularly by the Royalists. Nevertheless, it was a by-now old-fashioned gunpowder weapon that gave cavalry their common name during the Civil War itself: harquebusier. By 1642, most riders were, in fact, firing carbines, a weapon which was a cross between a musket and a pistol and which had a typical barrel length of 60 cm (24 in). Flintlock and wheellock pistols were also carried by cavalry riders, which used a piece of flint or pyrite to create a spark that lit the gunpowder. The older and more cumbersome matchlock trigger system could not be used while riding a horse. A pistol typically had a barrel length of 38-45 cm (15-18 in). Pistols, carbines, and swords were carried in a belt, often worn across the chest or, alternatively, a pair of pistols were carried in holsters in front of the rider's saddle.

Armour

At the beginning of the war, some riders continued to wear three-quarter length armour, that is armour that protected the head, chest, arms, and upper legs. A rider wearing this full kit was often called a cuirassier. As the conflict wore on and it became obvious that speed was just as vital a weapon as any other, armour was greatly reduced. There were also considerations of cost and the ineffectiveness of most armour against musket balls.

New Model cavalry wore a 'buff coat' – a long- or short-sleeved thick jacket made of leather that billowed out below the waist and which provided some protection to sword slashes. The coat was an expensive item, costing as much as the rider's horse. Over this jacket, they might wear a long leather coat in foul weather. The Parliamentarian New Model Army also issued cloaks to riders for protection from bad weather.

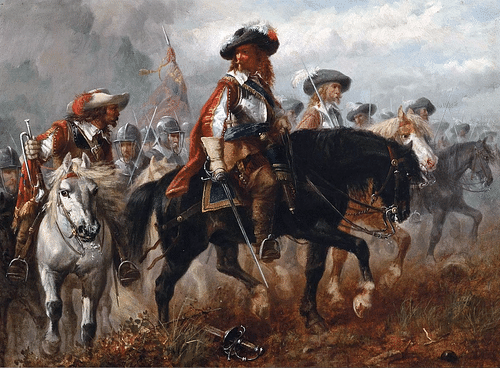

For ease of movement, cavalry wore less baggy trousers than the infantry and leather riding boots that went above the knee (but which could be folded down when dismounted). A common type of helmet was the zischagge or 'lobster-tail pot' which had a round crown, neck- and cheek-guards, and a front peak. The nickname derives from the overlapping metal strips of the neck-guard resembling a lobster tail. These helmets usually had three thin vertical bars to protect the face and so are sometimes called 'three-bar pots'. Breast- and backplates might be worn, and armour for the arm which held the horse's reins. Most riders wore leather gauntlets. Some riders had their reins reinforced with an iron or brass chain so that they could not be cut by an enemy's slashing sword. There were no uniforms as such for cavalry on either side, but brightly coloured sashes or scarves were commonly worn to identify who was who. At the outset of the war, Royalist sashes tended to be red, Parliamentary ones orange, but individual commanders had their own preferences.

Royalist Cavalry

The commander of the Royalist cavalry was the king's nephew Prince Rupert, Count Palatine of the Rhine and Duke of Bavaria (1619-1682). He was still in his twenties but had already gained experience as a cavalry commander in the Thirty Years' War (1618-1648) on the Continent. Prince Rupert' own cavalry regiment had around 10 units, with each composed of some 60 riders, although as with many other arms of the Royalist armies, numbers fluctuated throughout the conflict depending on availability and circumstances. Most other cavalry troops struggled to number 60, and the average was somewhere in the forties. Ideally, a Royalist cavalry regiment had 500 riders. A regiment was led by a colonel, and under him was a lieutenant-colonel and a sergeant major. Individual troop units were commanded by a captain who was assisted by a lieutenant, quartermaster, and three corporals. Each troop had two trumpeters who conveyed orders, and other specialists included a farrier, saddler, surgeon, and clerk.

Cavalry – both men and horses – were paid for by the king calling for his supporters to donate cash for that purpose. A cavalry rider cost around 2 shillings and 6 pence per day to maintain. It was the responsibility of individual commanders to find the necessary recruits and horses, and they were keen to do so, at least while the war went well for the Royalists, and so demonstrate their loyalty to the king.

Both armies trained their horses to become accustomed to battlefield noises and movements. Horses were trained to make tight turns on command, while riders were trained to handle their weapons on the move and to operate both within their unit and to participate effectively in wider regimental manoeuvres.

Parliamentary Cavalry

The New Model Army was created in 1645 and was initially composed of 11 cavalry regiments, 12 infantry regiments, one dragoons regiment (see final section), and two companies of 'firelocks' (artillery and musketeers). Each regiment bore the name of its commanding colonel. The 24 regiments grew to eventually number nearly 100, depending on circumstances. The enlarged army was thus broken down into 62 infantry, 28 cavalry, 4 dragoon, and a number of artillery regiments (although not all were active at the same time). Cavalry, like that in the Royalist army, operated in small groups. These troops consisted of around 60 riders with 10 officers early on in the war and expanded to up to 90 riders per troop plus 10 officers by the end, with six troops in a regiment.

The cavalry of the Parliamentary army was led by the Lieutenant-General of the Horse, a position first held by Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658), who was also the second-in-command of the New Model Army, its commander-in-chief being Sir Thomas Fairfax (1612-1671). Cromwell time and time again showed himself to be one of the great cavalry commanders of British history. The second-in-command of the cavalry, below Cromwell, was the Commissary-General of the Horse, and below this officer were two Adjutant-Generals of the Horse, a Quarter-Master-General of the Horse, and a Muster-Master-General of the Horse.

The colonel (or the lieutenant-colonel), sergeant-major, and captains each led a troop unit. The diversity in cavalry composition was reflected in such special units as Cromwell's own cavalry force, known as 'The Ironsides', which had 14 troops. At the beginning of the war, a Parliamentarian infantryman received 8d a day, while a dragoon got 1 shilling 6d, and a cavalry rider 2 shillings. In addition, cavalry riders could claim certain additional expenses such as maintaining horses. The horses themselves were first hired out to the army, but from mid-1644, Parliament obliged the counties in their control to provide them. Both Royalist and Parliamentary armies also confiscated horses they came across in enemy-held areas, a theft which in no way endeared them to the local communities.

The cavalry of the New Model Army proved its worth in June 1645 at the Battle of Naseby in Northamptonshire. The Royalists, numerically inferior, were destroyed by the well-trained and well-disciplined Parliamentarian cavalry.

Tactics

Cavalry was almost always stationed on the flanks of a Civil War army with units of infantry holding the centre of the battlefield. Several hundred cavalry riders were usually kept as a reserve behind the main lines for use wherever they might be needed as the battle developed. In most battles, cavalry began by attacking the enemy cavalry. Units often rode at a steady trot in ranks of three (and less commonly up to six), each rider with his knee almost touching that of his neighbour. There was about one horse's length between each rank. The best riders were usually in the front line and the next best group stationed at the rear of the troop.

Riders either shot their firearms before contact (in which case they reduced pace considerably) or at point-blank range after the initial clash of horses and men. The aim was to break up the enemy's formation using speed and force since singular and retreating horsemen were much easier targets. This use of cavalry as shock troops who attacked right from the off was employed by Prince Rupert with great success in the early years of the war and was the fruit of his experience in Continental Europe. The Parliamentarians, seeing the devastating combined effect of speed, power, and gunfire only too closely, soon adopted this approach to cavalry warfare themselves.

If successful in routing the opposition horse, the cavalry could then turn on the enemy infantry. Cavalry had to be wary of the pikemen and musketeers. Infantry could be routed by cavalry if attacked from the wings or rear, or if they had broken up their formation, but facing an organised volley-fire from ranks of musketeers or a bristling hedgehog of pikes, which were 5.5 metres (18 ft) long, was another matter.

Another problem was keeping a unit together after a cavalry charge, particularly when selecting a secondary target like a particular infantry unit after having routed the opposition horse. Many Civil War battles were won through discipline, not necessarily courage in arms or numerical superiority. Chasing too far after a fleeing cavalry unit or occupying oneself with looting deprived a commander-in-chief of vital forces that could be used in the heart of the battle.

The most infamous episode of a cavalry unit gaining a great advantage but then leaving the field to loot a baggage train far to the rear was the cavalry of Prince Rupert at the Battle of Edgehill in October 1642. In fairness, it was notoriously difficult to get cavalry units to perform a new manoeuvre mid-battle, but Oliver Cromwell famously managed it at the Battle of Marston Moor in July 1644 when he routed the opposing wing of cavalry, attacked the enemy infantry, and then crossed the battlefield to aid the other wing of Parliamentary cavalry.

Finally, Civil War armies had a specific type of cavalry, the dragoons, who carried similar arms to ordinary cavalry. They were a sort of hybrid infantry-cavalry unit who wore less armour and who had inferior horses, not the large and sturdy mounts full-cavalry riders had. Dragoons very often dismounted for actual fighting. Dragoons were, for this reason, often used to secure specific areas of the battlefield that might be advantageous such as a bridge, a hill for artillery to use, or an area of woods and hedges which could provide cover for musketeers. Dragoons could provide covering or supporting fire to the cavalry troops, and they might be used for small raiding parties, as scouts, as camp guards, to forage for supplies, and to protect the main army's chain of supplies. Eventually, dragoons became regular cavalry as the distinctions between the two troop types disappeared and commanders moved towards light cavalry as the best way to use horses in battle.