Dragoons were hybrid cavalry-infantry troops during the English Civil Wars (1642-1651). They usually dismounted before fighting and were used primarily as support troops. Dragoons were frequently tasked with capturing and holding strategically valuable areas of a battlefield such as bridges and passes that facilitated infantry movements, natural rises for artillery batteries, and cover such as buildings, trees, and hedges for musketeers.

Armed with muskets or carbines and more lightly armoured than full cavalry, dragoons became very valuable utility troops charged not only with operations during battles but also such duties as guarding camps and supplies, scouting, and policing. As European warfare developed, cavalry became less heavily armed and armoured so that they often became indistinguishable from dragoons, a term that in later periods came to be used as a synonym for light or medium cavalry.

A Special Type of Mounted Troops

In this period, dragoons were sometimes called "dragooners" or "dragons". It was the form of carbine weapon these soldiers carried, the dragon, which gave them their name. Dragoons typically rode inferior horses to the cavalry proper because they usually dismounted for battle, at least in the early part of the war. The historian M. Marix Evans explains how this happened in practice: "They rode ten abreast, and when they fought nine dismounted, throwing their reins over the neck of the horse next to them so the tenth could hold the horses of a whole rank" (24). For this reason, for many military theorists of the period, dragoons were classified more as mounted infantry than lightly armed cavalry who remained on their horses at all times. Essentially, the horse was merely a means to get the infantryman to a particular place on the battlefield faster than an ordinary musketeer or pikeman. Over time, the role of dragoons became more sophisticated as commanders tried to better their counterparts on what was becoming a much more dynamic battlefield.

Dragoons were present in both English Parliamentary and Royalist armies, as well as the Scottish army that fought at the battle of Dunbar in 1650. The best-documented dragoons are those in the Parliamentary armies, although even here, descriptions are inconsistent and patchy in their details. Parliament's New Model Army was created in 1645 with 11 cavalry regiments, 12 infantry regiments, and one dragoons regiment. This was the first time the dragoons had been so organised as previously they tended to be distributed amongst the other cavalry regiments, one troop of 100 dragoons per regiment.

The first notable commander of the Parliamentary dragoons regiment proper was Colonel John Okey (1606-1662) who commanded 676 men and officers at the Battle of Naseby in 1645. The New Model Army grew in size over the years, and eventually, there were four dragoons regiments. Each regiment bore the name of its commanding colonel, and the dragoons regiments reported to the overall commander of the cavalry, otherwise known as the Lieutenant-General of the Horse. He, in turn, reported to the commander-in-chief, the first being Sir Thomas Fairfax (1612-1671) and then, from 1650, Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658).

A dragoons regiment had a theoretical maximum of 1,000 men and was divided into ten companies, although the size of companies varied depending on the tasks set them and the availability of riders. If there was a shortage, it was usual for commanders to recruit dragoons from local militia units in the various counties where they were a relatively common type of soldier (their equipment being less expensive than cavalry). Each company was led by a captain or the colonel or his second-in-command, a lieutenant-colonel. A company had its own quartermaster and a cornet officer who carried the company colours. These colours were a variation of the regimental flag with a number indicating that company. The flags were like the cavalry flags and took the form of a square but ended in a swallow-tail on the right side. Illustrating its hybrid status between cavalry and infantry, there was a trumpet or cornet player (distinct from the officer of that name) and two drummers, the former being a typical element of a cavalry company, while the latter were only present in infantry companies. The cornet player and drummers gave signals for manoeuvres when the dragoons were, respectively, mounted or dismounted.

In terms of pay, a Parliamentary dragoon received 1 shilling 6 pence per day (compared to 8 pence for an infantryman and 2 shillings for a cavalry rider). Deductions could be made for the cost of clothing, equipment, and food (bread, biscuits and cheese when on the move).

Clothing

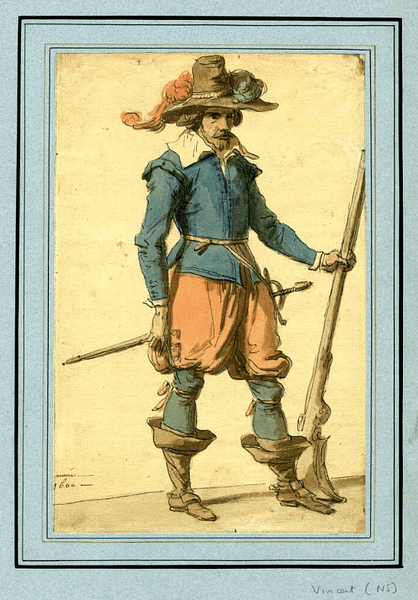

Dragoons began as mounted infantry, and so some even carried pikes, but their value as mobile troops soon meant they carried similar arms to ordinary cavalry. Their particular weapons then determined the best clothing to wear. Clothing and weapons were sometimes issued by the army, but there was no standard uniform as such. Coloured sashes were often worn, most often around the waist or diagonally across the chest, in order to distinguish who was who on the battlefield. Officers of any branch of the military continued to wear whatever suited them, only from the 1680s did a uniform become standard for them.

Dragoons usually wore less armour or none at all, and probably no helmet, preferring instead either the simple woollen or leather Monmouth cap or the soft felt hat with a wide brim that musketeers wore. Personal decoration might take the form of a few feathers or a coloured scarf where today a hat would have a band.

A typical dragoon could be dressed like a musketeer in other respects with breeches that ended at the knee and stockings. They had a short jacket, possibly in the Parliamentary Venetian red that some other troops came to wear as the war wore on. Alternatively, a dragoon might wear the leather 'buff coat' of a cavalryman, which protected the upper legs. In cold or wet weather, a long buttoned coat or cassock was worn. Long leather boots that reached the knee but which could be folded down were likely worn when more riding was required than footwork, otherwise, leather shoes would have been worn. It may be that some dragoons compromised between the two alternatives and wore shorter boots than the full cavalry version. It is clear from the historical record that dragoons were a still-evolving branch of the military, and the variations in clothing reflect this.

Horses

Another distinction from ordinary cavalry was that dragoons had inferior horses, usually smaller and less sturdy animals. This fact is indicated in records such as the New Model Army purchasing a number of horses in 1645. The price paid for a cavalry horse was £7 10 shillings, significantly more than the £4 paid for a horse destined for a dragoon. Another indication of the lower status of dragoons is the price Parliament paid for their saddles: 7 shillings 6 pence compared to the 16 shillings 6 pence paid for a cavalry saddle. The lack of quality horses and saddles was not such a problem as dragoons usually dismounted before actually fighting, and because they did not usually clash with the enemy on horseback, they did not need the extra supports at the back and front of their saddles that cavalry riders had. Most dragoons brought their own horse when first recruited, but an animal that died in battle or became too old for use was, at least in theory, replaced at the cost of the army and not the individual dragoon.

Weapons

Swords were worn by dragoons in a scabbard held in a belt around the waist or across the chest, but the particular style was up to the individual. Most swords had an iron hilt and a wide steel blade. Like cavalry, the dragoons carried firearms, either a musket or the shorter-barrelled carbine. Unlike most musketeers, dragoons typically had weapons with the faster and safer flintlock or wheellock mechanism (which used flint to create an ignition spark) and not the matchlock type. A matchlock firearm required a constantly lit match to operate, and so this was not a practical weapon for use on horseback regardless of whether the dragoon dismounted to fire it or not. The firearm was often carried over the shoulder or chest using a sling.

Like cavalrymen, some dragoons, especially officers, also had pistols, carried in a holster at the front of the saddle. As pistols fired a smaller bullet than a musket, they were usually only fired at a very close range to the enemy, even point-blank range if one's adversary was wearing armour. For greater ease of movement, dragoons may have kept their ammunition in leather cartridge boxes slung around the waist, rather than the more cumbersome bandolier belt worn across the chest by musketeers, since it was in this way easier to keep ammunition dry in wet weather when the box could easily be kept within the protection of a cloak.

Strategic Use of Dragoons

During the English Civil Wars period, the dragoon has been rather neglected by military theorists and in the contemporary accounts of the conflict compared to other troop types, but as the military historian J. Tincey notes, "In the day-to-day conduct of the Civil War, the dragoon proved to be the most useful of all soldiers" (23).

Only rarely were dragoons used like full cavalry, charging the enemy on horseback in a tight group, but they did do this at Naseby with success, where the Parliamentary dragoons led by Okey routed a group of Royalist infantry, captured their colours, and took 500 prisoners. Okey's dragoons then faced and beat a body of Royalist cavalry.

Besides these rare heroics, commanders more typically sent companies of dragoons to secure specific areas of the battlefield which would be advantageous to control. This might involve occupying an area, clearing it of enemy troops, or holding on to it under attack. Examples of these strategically valuable points were hamlets and villages, gatehouses, fortification walls, a rise where artillery might be stationed, a bridge or pass that would allow an attack or some form of retreat, or a wooded area or stretch of hedgerows which could provide cover for musketeers.

Dragoons were also used to provide covering fire or general support for cavalry troops, to conduct ambushes, to draw the enemy into the range of an awaiting body of infantry, and as small raiding parties behind the enemy's lines. Dragoons were also ideal for mopping up fleeing infantry after a battle. Other roles frequently given to dragoons included acting as camp guards, searching out supplies and foraging, accompanying artillery and the baggage train, and acting as scouts.

The New Model Army officially gave its dragoon regiment a full cavalry regiment status in 1650. However, as a result of dragoons being given such diverse tasks, it was rare for all ten Parliamentary companies to be present in the same field of operation. The term dragoon continued to be used for the four regiments of that type in the New Model Army of the 1650s and in other European armies, but, as field commanders moved towards lighter and lighter cavalry to gain greater speed on the battlefield, dragoons became less obviously a different type of mounted troops so that, eventually, they became a synonym for light or medium cavalry.