The battle of Dunbar on 3 September 1650 between the English Parliament's New Model Army led by Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658) and Scotland's army led by David Leslie (c. 1600-1682) was one of the last major battles of the English Civil Wars (1642-1651). The battle was part of the conflict between various English and Scottish armies now known as the Third English Civil War or Anglo-Scottish War (1650-51).

The Scots, keen to protect the Presbyterian Church in Scotland and see it thrive in England, rallied around Charles II, the eldest son of the late Charles I of England (r. 1625-1649), as they sought to continue the war between Royalists and Parliamentarians that had troubled England and Ireland over the last decade. Cromwell invaded Scotland in July 1650 and attempted to take Edinburgh, but, put off by its formidable defences, he was in full retreat when General Leslie took the fateful decision to try and destroy the English in the field. At Dunbar, the very opposite happened as Cromwell, with superior cavalry and aided by the Scots' poor choice of terrain, routed the Scottish army, turning near-disaster into one of the general's most famous victories.

The First & Second English Civil Wars

King Charles I had clashed with Parliament, particularly over money and religious reforms for years, and, finally, a civil war broke out in 1642. The 'Roundheads' (Parliamentarians) and 'Cavaliers' (Royalists) met in over 600 battles and sieges over the duration of the conflict. As the war went on, Parliament's superior resources began to tell, and its New Model Army won such significant engagements as the Battle of Naseby in June 1645. The First English Civil War (1642-1646) was won by Parliament.

Even in exile on the Isle of Wight, King Charles continued to plot his return to power, and he encouraged a Scottish army to invade England in 1648. The Scots were willing allies since they were keen to protect their own Presbyterian Church and to see it flourish in England.

At the Battle of Preston in August 1648, Cromwell and the New Model Army once more won a great victory and so terminated what became known as the Second English Civil War (Feb-Aug 1648). The king was tried for treason and warmongering, found guilty, and executed in January 1649. Even without its monarch and with the abolition of the institution of the monarchy in England, the Royalist cause was not dead yet. Supporters rallied around Charles' son, also called Charles, who was declared Charles II of Scotland in February 1649. The remaining English royalists and Scottish Covenanters, as they were called, rallied for one final attempt at defeating the Parliamentarians. So began the Third English Civil War. Before the Scots could be dealt with, Parliament first had to deal with a major rebellion in Ireland against the regicide. In the late summer of 1649, Cromwell, now commander-in-chief, led 12,000 men of the New Model Army and mercilessly crushed the uprising.

Edinburgh & Retreat

England and Scotland were, in many respects, reluctant foes in the Third Civil War. The Parliamentarians and Scots had previously been allies when Charles I had seemed the greater threat to the independence of the Scottish Church. Cromwell was certain that a show of force would persuade the Scots to see the error of their judgement in now supporting Charles II and then peace could be resumed. For this purpose, Cromwell marched to Berwick, and from there, on 22 July 1650, he led the New Model Army into Scotland with Major-General John Lambert (1619-1683) as his second-in-command in the field.

By now convinced of his invincibility after a long run of military successes, Cromwell stopped at the port of Dunbar just across the English-Scottish border on the east coast. Dunbar is around 32 kilometres (20 mi) southeast of Edinburgh, and it was an ideal port for Cromwell to receive his planned supply ships. The general then headed for Edinburgh and the very heart of the Scottish army. For it was at the capital that Lieutenant-General David Leslie, Lord Newark commanded a sizeable army of men garrisoned in Edinburgh Castle. Leslie (not to be confused with General Alexander Leslie, no relation) was an experienced campaigner, although not in terms of commanding a large army. Leslie refused to meet Cromwell in a single large engagement. Rather, the Scots harassed the English army in a number of skirmishes. Leslie had also barred the route to the capital by building a line of forts and entrenchments leaving Cromwell no choice but to retreat, at least temporarily.

Time was on Leslie's side since the longer they spent in the field, the more difficult it was for Cromwell to keep his army healthy and well-supplied, especially as the Scots were using scorched earth tactics. In addition, the Scottish levies were struggling to get men into the field, and so the extra time allowed more recruitment and, perhaps even more importantly, permitted troops to gather at Edinburgh from across Scotland. Leslie used his time well to further train his troops safely behind the massive battlements of Edinburgh Castle and its surrounding fortifications. The commander also reorganised his officer corps, although with only around 80 men dismissed, it was hardly the 4,000-strong debilitating purge that some English commentators described after the event.

The delay in a big confrontation certainly did not help the English. By the end of July, Cromwell needed more supplies to be shipped in by sea at Dunbar. He would have to return to the port. Cromwell headed there, the Scottish army in pursuit. Skirmishes followed at Musselburgh (Lambert was even briefly captured) and other points along the way back to the coast, all the time through foul weather.

One English captain, John Hodgson, describes the retreating English army as follows:

We…sent away our wagons and carriages towards Dunbar, and not long afterwards marched, a poor, shattered, hungry, discouraged army; and the Scots pursued very close. that our rearguard had much ado to secure our poor weak foot that was not able to march up.

We drew near Dunbar towards night, and the Scots ready to fall upon our rear: two guns played upon them, and so they drew off, and left us that night.

(Hunt, 261)

Troop Numbers & Dispositions

Cromwell arrived at Dunbar on 5 August. His troops were rested, and the army was resupplied by ship. Cromwell then made a second attempt to march on Edinburgh but again was blocked, this time by a large Scottish army on highly unfavourable ground at Gogar, west of Edinburgh. He decided not to take the bait but again withdrew to Dunbar on 31 August, once again fighting a rearguard action as the Scots pursued him.

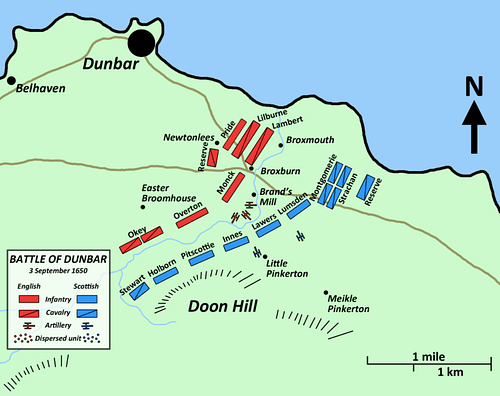

The Scottish army and the New Model Army began to assemble themselves for a full-on battle on 2 September. The New Model Army was packed full of battle-hardened veterans (although there were some novice pressed men, too) while the Scottish army was mostly made up of conscripts with little experience, a fact which greatly diminished their numerical advantage. Both armies were well-equipped for the period.

English sources after the battle put the total Scottish strength at between 22,000 and 23,000 men (up to 16,000 infantry and 7,000 cavalry). The military historian S. Reid puts the figure at a more realistic maximum of 13,000 men (9,500 infantry and 4,500 cavalry) and probably less given the recruitment problems and recent losses due to skirmishes and disease. On the other side, Cromwell had commanded some 16,500 men (11,000 infantry and 5,000 cavalry) when he had crossed the border, but he had suffered similar losses in skirmishes and to disease so that, at the battle of Dunbar, the New Model Army was probably composed of around 11,000 men (7,500 infantry and 3,500 cavalry). The disparity in the size of the two armies then would not have been so great as has been traditionally held, perhaps 2,000 more in favour of the Scots, and so certainly not the great disadvantage Cromwell presented in his report after the battle.

Initially, when the Scots had sent a force to Cockburnspath to cut off an English retreat southwards, some of the New Model Army commanders were put off by the size of the Scots army and wanted to abandon the position; their highly impractical idea being to try and leave in the supply ships at Dunbar. However, Cromwell had been given one advantage by the enemy. The Scottish ranks were not ideally positioned as the hilly terrain (particularly Doon Hill) behind the Scottish army might prove an ally since in front of them was a clough or ravine, the Broxburn, where the river ran through to the sea. There were only a handful of crossing points across this ravine. Consequently, trapped between these two natural features, the Scots would not be able to manoeuvre if the English cavalry (on their left wing and the Scots' right) could better their counterparts and attack the flank of the Scottish infantry. The key to exploiting the topography would be surprise and aggression.

Battle

It was a testing night for the men on both sides as they awaited their fate next day on the bleak Scottish coast, as Thomas Carlisle memorably described:

The night is wild and wet; the Harvest Moon wades deep among clouds of sleet and hail. Whoever has a heart for prayer, let him pray now, for the wrestle of death is at hand…We English have some tents; the Scots have none. The hoarse sea moans bodeful, swinging low and heavy against these whinstone bays; the sea and the tempests are abroad, all else sleep but we…

(Hunt, 262)

The battle commenced before dawn on 3 September when the English attacked first, as was typical, with their artillery and cavalry. Cromwell had an advantage in the former since he had shipped in heavy cannons. The Scots, on the other hand, because of the poor roads in the region, could only move smaller leather-covered cannons to the battlefield. The advantage was only a small one since no battle in this period was ever decided by artillery alone. The Scots had no more than 32 artillery pieces in all, while Cromwell stated he had had two pieces per infantry regiment, which would make 18 in total.

The English cavalry on the side of the battle closest to the sea and led by General Fleetwood charged. Both armies had bulked up their formation on this more open part of the battlefield. The infantry of pikemen and musketeers then engaged across the clough with not much to tell the difference between the two sides in terms of weapons and clothing except the distinctive blue bonnets worn by many of the Scots.

The English heavy cavalry, armed as usual with swords and pistols, was first repulsed by the mounted Scottish lancers, but they eventually routed their opponents, thanks to Cromwell sending in his large cavalry reserves which were composed of his best troops. The larger horses of the New Model heavy cavalry ultimately proved a crucial factor against the Scots' light cavalry lancers. Then, as perhaps planned (historians are not in agreement as to the original battle plan), the New Model horse paused, regrouped, and swung inland to engage the Scottish infantry whose right wing had already collapsed.

The English infantry, or at least part of it, was led by the vastly experienced General George Monk (1608-1670), and the fighting was intense for two hours, but the combination of cavalry and infantry crushed the Scottish army. Some of the Scottish formations broke up as they tried to retreat, but they were pursued and routed in a running battle westwards towards Haddington. Other Scottish brigades fought to the last man, but some others did make a more organised rearguard action. All in all, though, Dunbar was a disaster for Leslie's army, the remnants of which, mostly his infantry left wing, fled and gathered at Stirling. Around 3,000 Scots were killed and perhaps 6,000 taken prisoner after the battle. Cromwell had, once again, overseen a great victory, but the war was not quite over.

Aftermath

Cromwell then marched to Edinburgh for the third time. While the city gave itself up without a fight on 7 September, the castle did not and only fell, after a long siege, on Christmas Eve. In the meantime, Cromwell had pursued Leslie to Stirling where the Scottish army was bolstered by new levies arriving (likely troops who should have been at Dunbar). Stirling's great defences and Cromwell's lack of artillery led the English commander to withdraw and concentrate on Edinburgh Castle.

The Anglo-Scottish conflict dragged on as Charles II was formally crowned at Scone on 1 January 1651. The king continued to incite revolt and moved into England and on to Worcester for that purpose. Cromwell then defeated an invading Scottish army, again led by Leslie, at the Battle of Worcester on 3 September 1651 (exactly one year after Dunbar). This was the last major engagement of the English Civil Wars. On 16 December 1653, after reducing Parliament's membership to bolster support for the military, Cromwell was appointed the Lord Protector of England, Scotland, and Ireland. The new Republic was divided into ten military districts, each led by a major-general. Charles II had meanwhile fled to France, but the troubled Republic would only last until 1660 and the full Restoration of the Monarchy.