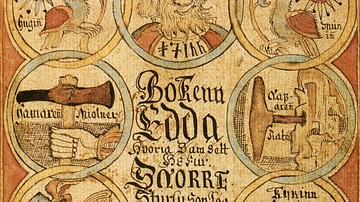

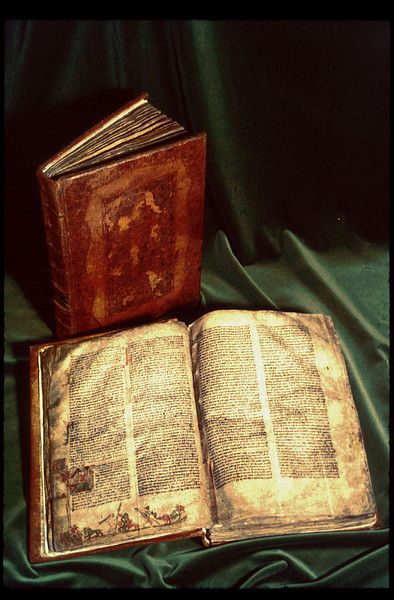

The poem Lokasenna belongs to the Poetic Edda, a bulk of Old Norse poetry written down in Iceland in the 1200s but based on linguistic features dating back as far as the 900s. In this invaluable resource for Norse mythology, Lokasenna stands out as one of the most vigorous poems of the collection, consisting of Loki's taunts to the assembly of gods and their unsuccessful attempts to get back at him.

Loki, son of the giant Fárbauti and goddess Laufey, is perhaps one of the most controversial and complex characters of Norse myth, with no easy way to straightforwardly define him. In the sources, he is called the sly god, who always seems to get involved in mischief, slander the other gods, or act as a great deceiver. However, some stories feature him as a very cunning and useful assistant to the gods.

The Poem

The Lokasenna is one of the less popular poems of the Poetic Edda, preserved in the manuscript Codex Regius, which we should nevertheless appreciate for its wittiness, aspiring to present us the gods in a less solemn and glorified manner, with more entertaining, daring and even scandalous overtones. The concept of a dialogue where the speakers attempt to challenge each other with shameless insults would definitely have gained a satisfied audience among the Norse. The poem alludes to some stories that unfortunately have not survived.

The title means "Loki's Truth-Telling," and the poem comprises Loki's exchange of insults with twelve gods and two servants, and it might be very probable that the exchange was dramatically performed. There are markings with the first letter of the gods' names in the manuscript, and the prose additions might suggest the existence of something similar in preceding manuscripts. It must have triggered a comical effect if we take into consideration the foul language often used in the poem. One of them, the worst insult possible in fact, is argr or ragr, roughly effeminate, unmanly, coward, even homosexual, thus completely out of the question in an extremely masculine society like the Norse. Throughout the poem, Loki makes extensive use of insults concerning problematic relationships or sexuality. While the vocabulary concerning men appears a little more diverse, women are generally blamed for their lustful behaviour, including their affairs with Loki himself. This points to stricter gender roles than those imagined in popular culture.

Loki Enters

The poem begins with a prose introduction where we find out about a gathering of many gods, goddesses, and elves in the hall of Aegir, a personification of the sea, located according to the Prose Edda on the island Hlesey (Danish Læsø). Thor, however, is absent, as he journeyed east, to the realm of the giants. It is presented as a majestic and peaceful place, with glittering gold and ale pouring itself. Jealous of the praise the two servants of Aegir received, Loki kills the one called Fimafeng. The gods then shake their shields and drive him away. After a while he returns to speak to the other servant, Eldir, inquiring about the "ale-talk" going on. Eldir replies that they are talking about their deeds of war, warning him that he would find no friends there. Loki maliciously looks forward to getting involved in their talk, willing to bring slander and hatred to the conversation. Eldir warns him once more, but Loki walks into the hall, acting like a helpless wanderer in need of a drink, and demands he either be given a seat or ordered away. The god Bragi sharply tells him they will prepare no seat for him, as they know very well whom they want to share a feast with.

In a rough translation, Loki replies:

Remember, Odin,

that a long time ago

we both mixed our blood,

then you promised

to pour no ale

unless it was for us both. (stanza 9)

The mingling of blood when men swore blood-brotherhood was carried out literally, and such promises that accompany the ceremony also occur in the sagas. The importance of the act is confirmed by Odin's decision to call out Vidar, his son, to offer his seat to the wolf's father, a reference to Loki's son Fenrir, the wolf that will swallow Odin at Ragnarök and will then be slain by Vidar.

The Great Insult Match

After stanza 10 the actual wrangling begins, as Loki hails the gods and goddesses and their very holy group. Bragi is willing to give him his horse and sword and he would even pay him with an armring to prevent him from arousing the wrath of the gods. Loki tells him he would lose both horse and armring and accuses him of cowardice. Loki is unimpressed by Bragi's threats to make him pay with his head, calling him an adorner of benches, an offensive phrase implying his womanliness Bragi's wife, the goddess Idunn, responsible for the apples of youth, intervenes; she asks her husband not to speak words of insult to Loki. Stanza 17 begins with the refrain for the rest of the poem: "Silence!" Idunn is mercilessly classified as most lustful for men, but she calms down her beer-cheerful husband, as she does not wish him to fight in rage.

The next stanza features Gefjun, a mysterious goddess not mentioned anywhere else in the poems, urging them not to exchange hurtful words. Loki replies that a fair boy seduced her mind by offering her a valuable gift, which convinced her to lay her thigh next to him. We can speculate that Gefjun might actually be Frigg, Odin's wife, given Odin's reply:

Loki, you are mad

and out of your wits

to rise the wrath of Gefjun,

because she knows everything about

the fates of this age

just like I do. (stanza 21)

Frigg would seem to share Odin's knowledge of fate. Odin is accused of often giving victory to the slower ones, which suits Odin's opportunistic nature as he chooses the best for Ragnarök. Odin makes use of Loki's questionable sexuality, calling him a milking cow and a woman bearing children, truly of unmanly nature. In fact, Loki did bear children; he turned himself into a mare to distract the horse of the giant tasked with building the gods a fortress. One could taunt another man with bearing children in such a contest of abuse.

The next stanza mentions Odin's dealings with dark magic on the island called Samsey, particularly associated with mysticism. This is also a hint at Odin's ambivalence, even queerness, as a sign of boundary-breaking, as women were the ones involved in the practice of (dark) magic. "You went in witch's guise among men," Loki says, "and struck a drum like a seeress." Frigg replies that whatever they did should be regarded as ancient events, and one should never tell people about one's fate. Unimpressed, Loki just repeats the refrain "Silence!" and accuses Frigg of lustfulness. He offers as evidence for the slander an episode when Frigg would have slept with Odin's brothers, Vili and Vé. The Ynglinga saga, the first story – and attempt at presenting the gods as historical figures – from the cycle Heimskringla (Orb of the World) by 13-century Icelandic scholar Snorri Sturluson mentions this episode.

Frigg threatens him in vain that if her son Baldr had been there in the hall, Loki would not have escaped the wrath of the gods. This allows Loki to remind her that he was responsible for Baldr's death, in which he takes great pride. The story is told fully by Snorri: Frigg had demanded all creatures to swear not to harm her son, a being of light, except for the mistletoe deemed too young. Loki the trouble-maker guided a twig of mistletoe in the hand of Baldr's blind brother Hodr, accidentally slaying him. In stanza 28 we read:

Then, Frigg, you want

that I further count

my evil deeds,

I am to blame

that you no longer see Baldur

riding home to the hall.

Freyja, daughter of Njord and sister of Freyr, deities associated with fertility, reiterates the might of Frigg and her fortune-telling abilities, only to get slammed herself by Loki. Not taken aback by Freyja's reply, Loki continues the wrangling by telling her she is a witch blended with many curses, either she conjures them or is subjected to them. Njord comes to the rescue and calls Loki a homosexual god who bears children. Foul language abounds as Loki refers to Njord's origin from the other family of gods, the Vanir, perceived as inferior. Njord was a hostage of the Æsir family of gods, and the daughters of Hymnir – a frost-giant – used him as a urinal. There is little to counteract such an offensive slur, as Njord only mentions his utmost reason of pride, his son Freyr, a leader whom no one hates. Loki diminishes his boast by reminding him he is, in fact, the product of his relationship with his sister, a detail supported by the Ynglinga saga.

Tyr, another battle god defends Freyr as honourable, and it is a good occasion for Loki to make use of the episode with his son, the wolf Fenrir, enchained with a magic fetter. Tyr was given the dangerous task of tricking the wolf into accepting the fetter, and he vouched with his hand in the wolf's mouth that the bond shall break, thus sacrificing his limb in the process. Loki mocks his limblessness, and in a rare instance of almost compassion towards Loki, Tyr acknowledges that they both suffer a loss, one losing an arm, and the other a son. The next stanza resumes the bashing with sexual content, as Loki boasts about having had an affair and even a son with Tyr's wife.

Freyr then warns Loki that soon he will be on the road to destruction if he does not stop. Freyr's skeletons in the closet include his purchase of Gerd, giant Gymir's daughter, and having sold his sword in the process, which will leave him utterly defenceless at Ragnarök. Loki pities him, but Freyr's servant Byggvir intervenes aggressively. Loki does not take the servant seriously and releases a plethora of insults at him, revolving around cowardice.

The next two stanzas deal with the exchange between Loki and Heimdall, the deity acting as both the guardian of the gods and forger of social classes, whose antagonistic relation to Loki will end up in a duel at Ragnarök, according to Snorri. Heimdall shares a bit of didactic wisdom in stanza 47, calling Loki drunk and thus not in his right mind, since excessive drinking causes every man to not remember their words, echoing similar advice given by Odin in Hávamál. Loki mocks Heimdall for having to endure an ugly fate since he must always stand up straight as a watchman.

Stanza 49 serves as a foretelling for the epilogue of Loki challenging the gods. Skadi, the wife of Njord and daughter of giant Thjazi, warns him that his loose tongue will still when the gods bind him to a sword (Snorri says a rock) with the bowels of his dead son. According to the prose note at the end of the poem, the gods bind Loki with the entrails of his son Váli, turning the other son, Narfi, into a wolf. In Snorri's version, Váli is the wolf, who tears his brother into pieces, and the gods then use his bowels to bind Loki.

Although he knows he cannot avoid his fate, Loki mentions that he witnessed the deadly fight where Thjazi was caught (told in Snorri's Skáldskparmál and briefly hinted at the Poetic Edda – Thjazi's daughter Skadi had married Njord as compensation). With a slightly ominous undertone, she says that in this case, from her holy places only cold council shall come for him, a leitmotif related to women's ruthless advice in the sagas as well. If they start counting their flaws, nevertheless, she would be running at a loss, given her affair with Loki. Noticing how all goddesses have to tolerate his incessant slurs, Sif, Thor's wife pours Loki some mead, asking him to spare her of the foul talk, as she is blameless. Loki, however, claims to have been his lover by deceit.

Thor to the Rescue

Beyla, servant Byggvir's wife, foretells in stanza 55 the arrival of Thor, who will definitely silence the slanderer. Soon Thor storms in, and he threatens Loki with his hammer. He also employs the motif of unmanliness, calling him a wimp and threatening to cut off his head. Loki continues playing with the theme of cowardice, slamming Thor for not being able to defend Odin from Fenrir. According to the poem Völuspá – about the beginning and end of the world – and Snorri, Thor will fight Jörmungandr, the world-serpent, another son of Loki. An enraged Thor thunders:

Cease, you unmanly creature,

or the mighty hammer

Mjollnir will shut you up

I will hurl you up

And out in the East

Where no one will see you again.

The "East" refers to the land of giants. Loki taunts Thor that he hid in the thumb of Skrymir, a giant who tricked him. The same topic is used in the contest between Odin and Thor in the poem Hárbarðsljóð (The Lay of Greybeard). Loki makes one last attempt after Thor threatens to break every one of his bones, a reference to the same adventure. He finally gives up faced with Thor's might, boasting that he spoke his mind. In the last stanza, he tells Aegir, the host, that he will not be making such a feast again, wishing that fire would burn everything he owns, probably a reference to the fire that consumes the whole world at the end, according to Völuspá.

The prose epilogue describes the binding of Loki, above whom Skadi fastens a snake dripping poison. Sigyn, Loki's wife, holds a pot to gather the poison, but when she empties it, the poison drops on Loki's face, and his struggles cause earthquakes. Snorri provides another and perhaps more plausible explanation for this punishment, namely the death of Baldr, although adding insult to injury did have dire consequences in Norse society.

Conclusion

Many of Loki's accusations are known from other sources, while others, chiefly the ones referring to the various sexual encounters but also other small details, are only found here. It is not that odd to imagine that the Norse would have enjoyed such comical material about their gods, as classical literature features similar examples. The poem's conclusion also pinpoints the major role Thor played for the commoner, consistent with many other poems, as the keeper and defender of order.

The poem mirrors some essential aspects of Norse society: offering hospitality, the culture of manliness, the fear of sexual deviance, the practice of magic, rules of acceptable conduct limiting sexual behaviour especially for women, and the importance of skillfully composing verses to engage in verbal fights. As for Loki, the poem clearly focuses on his image as a trickster. He is tolerated probably due to his common oath with Odin, and he nonchalantly proceeds to reveal uncomfortable truths about everyone. His party-crashing and vulgarity definitely have their share of charm.