The affair of the diamond necklace (1784-86) was a scandal that centered around Queen Marie Antoinette of France (l. 1755-1793). Although the queen was innocent of any involvement in a plot to steal a luxurious diamond necklace, the scandal succeeded in ruining her already damaged reputation, causing increased disillusionment in the monarchy in the years preceding the French Revolution (1789-1799).

The Necklace

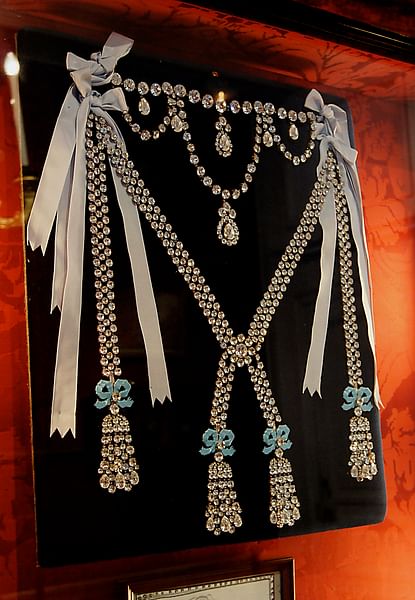

In 1772, two Parisian jewelers by the names of Boehmer and Bassenge began work on a magnificent diamond necklace, unmatched in its splendor and grandeur. It is speculated that they intended to sell it to King Louis XV of France (r. 1715-1774), who was well-known for showering Madame Du Barry, his latest infatuation and chief royal mistress, with lavish gifts.

To the jewelers' satisfaction, the completed necklace was garishly ostentatious, containing 647 brilliants and weighing 2,800 carats, fit for any royal mistress. However, upon finishing the necklace, Boehmer and Bassenge were faced with two big problems: the first being that their hopeful patron Louis XV had died of smallpox before they could sell it to him. The second, that the woman for whom the necklace had been intended had been exiled from court by the dead king's successor, King Louis XVI of France (r. 1774-1792) at the behest of the new king's wife, Queen Marie Antoinette. So, with neither prospective buyer nor recipient around to collect the gift, the jewelers were faced with the ruinous possibility of never selling the necklace which, priced at around 2 million livres, was monstrously expensive.

The jewelers tried to sell it to Marie Antoinette, who seemed the most obvious candidate. The queen was, after all, known for her indulgence in fashion. Unfortunately, the necklace proved too much for Marie Antoinette, who, as a bitter rival of Madame Du Barry, may have disliked it due to its association with the woman, or may just have found it to be too ostentatious for her tastes. In either case, she refused it, even when the jeweler Boehmer, appealing to the queen's known weakness for emotional display, made a scene at court, "sobbing his eyes out, yelling, swooning and threatening to do away with himself unless the Queen took the necklace off his hands" (Schama, 204). Such theatrics had no effect, however, and Marie Antoinette again refused him, stating that the French crown had "more need for Seventy-Fours [naval ships] than of necklaces" (Carlyle, 53). She then advised Boehmer to break up the necklace and sell the separate stones before sending him away. To the queen's mind, that was the end of the issue, but in a roundabout way, the necklace helped bring about the abolition of France's monarchy.

The Cardinal & the Trickster

Cardinal Louis de Rohan (1734-1803) descended from a family with a history of conspiracy, who, in the words of historian Simon Schama, were "too rich for their own good" (Schama, 206). Cardinal de Rohan, former ambassador to the Austrian court at Vienna, was a womanizing and dissolute man who was described by Empress Maria Theresa of Austria (r. 1740-1780) as "a dreadful type...without morals" (Fraser, 63). This disapproval was shared by the empress' daughter, Marie Antoinette herself, whose influence meant that the cardinal was kept at arm's length from any of the goings-on at the French royal court of Versailles. This was an embarrassment to a man with such an esteemed title and lineage as Rohan, who sought to enter the queen's favor so he could gain influence at court and perhaps even secure a position as one of the king's ministers. Rohan would finally see his chance when, in 1783, he began an affair with a woman named Jeanne de la Motte.

Jeanne de la Motte was descended from an illegitimate line of the royal Valois Dynasty and could trace her ancestry back to King Henry II of France (r. 1547-1559). Although she was raised in poverty by her peasant mother, Jeanne never forgot the royal blood passed down to her through her father. In 1780, at the age of 24, she married Nicolas de la Motte, an officer of the gendarmes, and the couple took advantage of Jeanne's noble ancestry and styled themselves as Comte and Comtesse de la Motte, adding de Valois to their name. Eventually, she found a patron in the Comtesse de Provence, sister-in-law to the king, from whom she received a modest pension, but this was not enough for Jeanne.

By the time Jeanne became acquainted with Cardinal de Rohan, she was living with both her husband and her lover, a pimp and forger named Rétaux de Villette. Once she became the cardinal's mistress, Jeanne quickly discerned Rohan's obsession with elevating himself to Marie Antoinette's favor. Although Jeanne had never met the queen, she saw an opportunity for profit and set about convincing Rohan that she was an intimate of Marie Antoinette's and could help him in his plight. Blinded by the prospect of achieving his ambitions, Rohan did not question the truthfulness of his new mistress' claim but, instead, asked if she could arrange for him to meet with the queen. Jeanne agreed to help.

The Affair

Conspiring with her husband and Villette, Jeanne wasted no time coming up with a scheme that involved ripping off Rohan, the Crown, and the Parisian jewelers, while making off with a large sum of money and the diamonds themselves. The first phase of the plan was to get rid of any doubts in Rohan's mind that he was dealing with the queen herself. So, on 10 August 1784, Jeanne arranged a midnight meeting between "Marie Antoinette" and Cardinal de Rohan at the Grove of Venus in the gardens of Versailles. Of course, it was not really the queen Rohan would be meeting with, but Nicole d'Oliva, a Parisian prostitute who possessed a striking resemblance to Marie Antoinette.

Nicole appeared to the cardinal with her face obscured by a headdress, wearing one of the white muslin dresses Marie Antoinette was known to adore. Since the meeting took place in semi-darkness, Rohan fell for the ploy. The façade was sealed when Nicole presented Rohan with a rose, accompanied by the words: "You may now hope that the past will be forgotten" (Fraser, 238). This clandestine and scandalous meeting was enough to stir much excitement in a man such as Cardinal de Rohan, so when Jeanne periodically asked him for sums of money to go toward the queen's favorite charities, the cardinal happily obliged. He believed every livre would go toward his advancement in the queen's good graces. Instead, the money went toward Jeanne de la Motte's favorite dressmaker.

Once Jeanne had been receiving money from Rohan for long enough, she presented him with a letter that was supposedly from the queen. The letter stated that the queen greatly desired a certain diamond necklace and wanted to wear it for the coming Candlemas celebration but did not want to be seen spending the funds to purchase it during a time of need. The letter commissioned Rohan to buy the necklace for her, asking him to pay the jewelers in four installments and send the necklace to the palace. The letter was signed "Marie-Antoinette de France," which should have been a sign that it was a forgery since it was well-known that royals at the time signed formal correspondence only with their baptismal names. Rohan, a former ambassador, should have been aware of this. Yet for whatever reason, this detail went overlooked, and the cardinal went ahead with the process to purchase the necklace.

Boehmer and Bassenge were delighted to finally get the necklace off their hands. On 29 January 1785, they delivered it to the cardinal's estate after negotiating to sell it to Rohan at the discounted price of 1.6 million livres, to be paid in four installments as per the "queen's" instructions. A while later, Villette, posing as the queen's courier, came by to pick up the necklace. Rather than bringing it to the queen, Villette smashed it apart and removed the gems. Jeanne's husband Nicolas then took the gems with him to London where he sold them piecemeal to English jewelers. It appeared, for the moment at least, that the scheme had gone off flawlessly.

Before long, the victims began to take notice that no necklace had ever been delivered to the queen. Candlemas came and went and Rohan, who had been waiting eagerly to see the queen wear the necklace he had gone through great pains to procure for her, was dismayed when she had not worn it. Nor did she wear it in the weeks and months to follow. This greatly disturbed Boehmer as well, who never received Rohan's first payment of 400,000 livres that was due on 1 August. Getting desperate, Boehmer sent the queen a note on 12 July 1785, inquiring if the necklace was to her satisfaction. The queen, confused and irritated at hearing from Boehmer, simply burned the letter.

When he received no reply, Boehmer went to see Madame Campan, a lady's maid in the queen's service on 5 August. When Madame Campan informed him that the queen had burned his letter, Boehmer became enraged and blurted out, "The Queen knows she has money to pay me!" (Fraser, 230). When a confused Madame Campan pressed for details, Boehmer revealed that he had been dealing with the queen through Rohan and produced the letters bearing Marie Antoinette's forged signature. Madame Campan took this information to the queen, and on 15 August, Cardinal de Rohan was summoned to Versailles by the king himself.

The Scandal

Rohan appeared before King Louis XVI still in his scarlet pontifical robes, as he had been preparing to perform mass. Louis met him alongside the queen and Keeper of the Seals Armand de Miromesnil. Immediately, the king asked the cardinal to explain himself, asking him where the diamond necklace currently was located. Confused, Rohan responded that he had believed it to be with the queen. When the king made it clear that this was not the case, Rohan, finally realizing he had been cheated, revealed how he had been commissioned by the Comtesse Jeanne de la Motte, who had presented him with forged letters. He emphasized that all he had done was to please the queen.

Far from placating Louis XVI, this explanation only seemed to infuriate him. For one thing, Louis had lately become especially defensive on all matters relating to his wife. The recent birth of the royal couple's second son, the future Louis XVII of France, had reinvigorated their marriage, while an increase in the circulation of the slanderous and often pornographic libelles attacking the queen had only strengthened the king's resolve on matters concerning Marie Antoinette. Another thing that infuriated the king was Rohan's supposed ignorance of the forged signature. Louis XVI, who "breathed royal etiquette since birth," could not understand how someone with the pedigree and diplomatic experience of Rohan would have overlooked such an obvious detail (Carlyle, 96). This led Louis XVI to believe that it was perhaps Rohan himself who was behind the forgeries. Despite Miromesnil's concern that it would not be a good look to arrest a cardinal in such a dramatic fashion, the king, gripped by rage, had Rohan arrested and taken to the Bastille.

Although Rohan was to later be depicted by his lawyer as "languishing in the irons of the Bastille," in truth he stayed in a furnished apartment outside the prison towers where he spent his nine incarcerated months entertaining a string of visitors (Schama, 208). Yet it was the word Bastille itself, a synonym for the tortures and cruelty of the Ancien Regime as far as French public opinion was concerned, that won the public to Rohan's side. Just as Miromesnil had predicted, many of the common people saw nothing but the unjust imprisonment of a godly man, a victim of the oppression of absolutism. Meanwhile, Jeanne de la Motte, who had unwisely called attention to herself by spending copious amounts of money on properties, was also arrested, along with the forger Villette and the prostitute Nicole d'Oliva. The famous occultist, Count Cagliostro, was also arrested in connection to Rohan, although he played no discernible part in the affair.

As the prisoners awaited trial before the Parlement de Paris, Marie Antoinette dealt with her distress over the ordeal. She vented her frustration in a letter to her brother, Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor, in which she vehemently denied that she had ever in her life signed her name "Marie-Antoinette de France." Even more humiliating, the creators of the libelles soon heard about Rohan's midnight rendezvous with someone he thought to be Marie Antoinette and wasted no time spreading rumors of a sexual liaison between the queen and the cardinal. Marie Antoinette was more horrified than usual at these lies since they involved a man she despised and were obviously untrue to anyone who personally knew her. Still, the common perception of the queen as a promiscuous and spendthrift foreigner caused rumors to spread like wildfire that the entire diamond necklace scandal was her fault.

The Trials

On 31 May 1786, the heavily publicized trials of Cardinal de Rohan and the occultist Cagliostro were held before the Parlement de Paris, followed shortly thereafter by the other conspirators. The trials were not without their political influences; the parlement, the most powerful of thirteen judicial courts overseeing France's provinces, had long been engaged in a struggle against royal authority and was eager to assert its independence.

Rohan's defense argued that the cardinal's only faults were his trusting nature and his urge to serve the queen, stating that he was as much a victim as anyone else. In the end, the parlement acquitted him, although he had to seek the king's pardon for his attempt at a midnight rendezvous with Marie Antoinette. This he was granted, on the condition that he make a large donation to the poor and be forever banished from court. Rohan was a free man, but the banishment from court saw his ambitions thwarted. The queen was said to have been disappointed by the verdict, but the crowds outside the trial cheered at the outcome.

Cagliostro was also acquitted, as was Nicole d'Oliva, who inspired the sympathy of the court with the news that she had delivered an illegitimate baby while imprisoned in the Bastille, and by her inability to get through any question in court without sobbing. Rétaux de Villette, who had forged the letters, was found guilty and banished from the kingdom. Nicolas de la Motte was tried in absentia, since he was still abroad in London, and condemned to servitude as a galley slave.

Jeanne de la Motte was also convicted and, as the mastermind behind the scheme, suffered the worst fate of all her conspirators. She was publicly stripped naked and whipped by the royal executioner, before being branded with the letter V (for voleuse-thief). Jeanne struggled so much beneath the executioner's grasp that the brand missed the target of her shoulder and scorched her breast instead. The display was indeed disturbing, and those who witnessed it would not soon forget it. After her public torture, Jeanne was sent to Salpêtrière, a woman's prison from which she would escape two years later, dressed as a boy. She made her way to London where, in 1789, she published her memoirs, which found a large audience since many people still remembered how she had been treated and sympathized with her. Jeanne de la Motte died in 1791, after falling from a London window while running away from debt collectors.

Significance

The affair of the diamond necklace permanently ruined the already sliding reputation of Marie Antoinette. Already accused by the libelles of being a sexual deviant who made lovers out of foreign princes, held orgies in the gardens of Versailles, and shared in the 'German vice' (lesbianism), the rumor of her affair with a cardinal in the aptly named Grove of Venus was too much for the French public to ignore. The fact that all these rumors were patently false (with the exception of one extra-marital lover, a Swedish count) did nothing to help the queen’s reputation. Nor did the fact that many people believed her to be an active enemy of the kingdom, a spy in the service of Austria, as well as a notable spendthrift who wasted the kingdom's money.

The mere association of the queen with the scandal, despite her lack of involvement in the actual affair, was enough for many people to paint her as a villain. She became so unpopular in the following years that she stopped appearing at public events and became a greater liability to her husband's image. The vicious gossip about her continued to ramp up until, during the French Revolution, she became a symbol of the dysfunctionality of the Bourbon monarchy and a scapegoat for everything wrong in France. She would become a popular target for the Jacobins, who would see to it that she was guillotined on 16 October 1793.

The Affair of the Diamond Necklace was neither an event that directly caused the French Revolution nor was it a primary reason for the abolition of the Bourbon monarchy. Yet coming as it did only four years before the start of the Revolution, the scandal helped to sow the anti-monarchical seeds that would sprout during the tumultuous revolutionary years.