Scandinavians from the island of Gotland began to spread throughout the Baltic region along the Russian rivers in the 700s. While the Vikings of Norway and Denmark from the 8th to 11th centuries are widely recognized as fearsome raiders and colonists, Gotlander traders were as much warriors as businessmen and advanced into new areas via fortified outposts.

Once the local people were pacified, new settlers were recruited to create towns and trading cities. This process was repeated over and over as the Gotlanders moved further east until their sphere of influence touched the Byzantine and Islamic worlds.

The Gotlanders came to be called Varangians, a name probably derived from the Old Norse word var, which means "union by promise". The Gotlandic merchants kept themselves together by making mutual oaths for defense and profit-sharing. The Varangians became wealthy by trading slaves, furs (beaver and black fox), and swords, and Arab dirhams became their favored medium of exchange.

Trade with the Muslims & Byzantines

The Gotlandic merchants who settled in the East Slavic area of modern-day northern Russia were called al-Rus by the Arabs. Rhos (Rus) came from the old Norse word ruotsi, which meant "expedition of rowing boats". Over time, these Rus assimilated with the native Slavs along the rivers and lost their distinct Gotland identity.

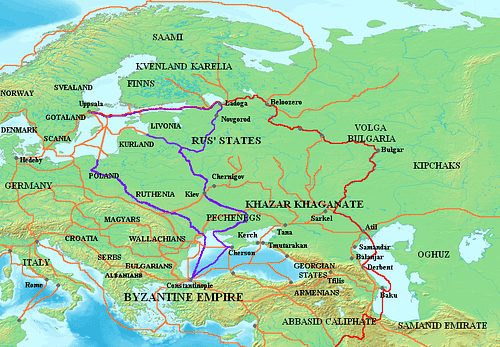

In the second half of the 700s, Rus traders began moving south down the waterways of northern Central Europe and established two major trade routes:

- down the Volga and across the Caspian Sea to the Muslim-held lands as far as Baghdad

- across the Black Sea to the Christian Byzantine Empire

Both these routes passed through the Jewish Khazar Kingdom where they were tithed.

The city of Baghdad must have been an amazing sight to the Rus. Between 903 and 913, the Arab writer Ibn Rustah wrote an eyewitness account that recorded the Rus had "no villages, no cultivated fields" and that "their only occupation is trading in sable and squirrel and other kinds of skins, which they sell to those who will buy them" (Gabriel, 3). Baghdad was now the crown jewel of the Islamic caliphates, a lavishly embellished city with expansive green parks and gardens, marble palaces, promenades, and finely built mosques.

The Rus traveled across their trade routes in pursuit of Arabic silver coins and silk, spices, wine, jewelry, glass, and books from the Byzantine Empire. In return, they traded captured Slavs from the Eurasian Steppe and offered fur, honey, wax, and timber. The silk trade can be traced from Constantinople, or Rayy in Iran, to Kiev and Novgorod, then into the Baltic and Scandinavia, and finally into England. Gotland has been pinpointed as the origin of this Eastern European trade network by the extraordinary amount of Islamic silver coins that have been uncovered there. The silver used to mint these coins came from mines within the Muslim-controlled provinces in Central Asia.

Formation of the Kievan Rus

In the late 9th century, Prince Oleg (879-912) of the Rurikid Dynasty of Varangians formed a loose federation in Eastern and Northern Europe which came to be called the Kievan Rus. Oleg established the Rus in 862 began with Novgorod as his capital (160 km south of Saint Petersburg) and extended his control from Novgorod south along the Dnieper River valley and ultimately moved his capital south to the more strategic Kiev (Kyiv in today's Ukraine).

At its greatest extent, the Kievan Rus ruled an area stretching from the White Sea in the north to the Black Sea in the south and from the headwaters of the Vistula in the west to the Taman Peninsula in the east. The modern nations of Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine all have Kievan Rus as their cultural ancestors. The Kievan Rus ruled for 700 years until they were defeated by the Mongols between 1237-1242.

Much is known about the Kievan Rus because of a manuscript called the Russian Primary Chronicle or Tale of Bygone Years, which gives a detailed account of the early Slavonic history from about 850 to 1110. A monk named Nestor is believed to have put it together in the court of Grand Prince Sviatapolk II of Kiev in 1113, using materials taken from other Byzantine chronicles, Slavonic literary sources, miscellaneous official documents, and oral sagas. The original manuscript is long gone, but several revisions still exist that were written centuries later; the earliest called the Laurentian codex from 1377 and a later one known as the Hypatian codex from the 1500s.

Rus Attacks on the Islamic & Byzantine Worlds

While most interactions between the Rus and Baghdad, the Khazars, and the other Muslim lands were peaceful, there were some notable exceptions. The Rus were so fearless that they periodically raided Byzantine and Muslim strongholds. Records of these confrontations have been left to us in The Russian Primary Chronicle and by several medieval Arab chroniclers including Ibn al-Athu¯r, who wrote a comprehensive 11-volume history of the world c. 1231.

In the first major confrontation in 860, a fleet of about 200 Rus vessels sailed down the Bosporus and attacked the suburbs of Constantinople. The attack took the Greeks completely by surprise in what Saint Photios the Great of Constantinople called a thunderbolt from heaven. The city was largely undefended at the time, as the Byzantine emperor, Michael III (r. 842-867), was away fighting the Abbasid Caliphate, and his navy was confronting Arab pirates of the Mediterranean Sea. After landing, the Rus went on a rampage, setting homes and churches on fire, as well as drowning and stabbing the residents. They subsequently retreated, for some unknown reason, after pillaging the suburbs.

The Rus launched another attack on Constantinople in 941, this time with disastrous consequences for them. They sent a massive fleet of 1000 ships to the city but were defeated by a small fleet of 15 old Byzantine warships fitted with greek fire projectors that spewed burning chemicals at the invaders. A large number of Rus ships and soldiers were set ablaze, and any soldiers who jumped overboard to escape the flames drowned, weighed down by their armour.

The Rus also launched a number of raids across the Caspian Sea into Muslim lands. In the largest in 913, a fleet of 500 Rus ships attacked the Gorgan region, in the territory of what is now Iran, where they plundered goods and took women and children as slaves. An army of enraged Khazars and some Christians eventually attacked and defeated them, leaving few survivors.

During another campaign in 943, a large Rus armada attacked the prosperous trading city of Barda on the south shore of the Caspian Sea. The local people fought them mightily by throwing stones and hurling abuse, but the Rus rounded them up and slaughtered 5000 of them. As described by the Arab chronicler Ibn al-Athīr’:

After this lasted for a long time, they ordered the people of the town to depart and [they said that] they would not attack the townsmen for an interval of three days, and an individual was free to leave with whatever possessions he could carry. Most of the townsmen remained [in Barda] after the appointed time, and the Rus then killed many people, and they took some ten thousand souls captive. They gathered those who remained in the Friday Mosque, and they said to the remaining townsmen: "You can either ransom yourselves or we will kill you." A Christian came forth and settled on twenty dirhams for each man. But the Rus did not keep to their bargain, except for the sensible ones, after they realized that they would not receive anything for some townsmen. They massacred all of those [for whom they could receive no ransom], and only a few fled from the massacre. The Rus then took the valuables of the people and enslaving the remaining prisoners, and took the women and enjoyed them. (Watson, 434)

The Rus used Barda for several months as a base for plundering the adjacent areas, but eventually, they were forced to leave when they were greatly weakened by an outbreak of dysentery from tainted fruit and had become isolated for defense in the citadel of Barda. They left the fortress at night, carrying on their backs what they could of their plundered treasure, gems, and fineries.

Varangian Guard & the Rise of Moscow

The Kievan Rus would form a tight bond with the Byzantines in 988 when their emperor Vladimir the Great (r. 980-1015) decided to lose his pagan ways and become an Orthodox Christian. He weighed his decision carefully, choosing the Orthodox Christianity of the Byzantines over the Judaism of the Kharzas, the Western Christianity of Rome, and the Islam of the Arabs, probably because it afforded him the most powerful alliance.

In recognition of their fearlessness, the Rus were recruited by Byzantine Emperor Basil II (r. 976-1025) to defend Constantinople. About 6000 Rus mercenaries were formed into the elite Varangian Guard to protect Constantinople and serve as the emperor's personal bodyguards. These mercenaries fought in every major Byzantine campaign from then until 1204: the sack of Constantinople by Crusaders.

When the Kievan Rus collapsed as a state after the Mongol invasion of Europe in 1237-1242, Moscow was an insignificant trading outpost. Over time, a series of princes expanded its borders and Moscow took over as the political and cultural center of the northern Rus lands. Moscow's remote, forested location shielded it from Mongol occupation and attack, and it was located near several rivers that provided access to the Baltic and Black Seas and the whole Caucasus region. Moscow gradually united the northeastern and northwestern Russian principalities throughout the 15th century, and it overthrew Mongol rule in 1480. Ivan III the Great (r. 1462-1505) became the first Moscow ruler to adopt the title of tsar and called himself Ruler of all Rus.