The forest is a habitat for people, animals, and plants, a provider of invaluable resources, and an ally in the fight against climate change. The greatest beneficiary of the forest is humanity – but it is also its greatest threat. Over the centuries, the relationship between humans and the forest has evolved and changed across time and space. A new exhibition at the Swiss National Museum in Zürich, Switzerland – In the Forest: A Cultural History – shows how this transformation has had a profound and lasting impact on culture, art, and literature. In this interview, James Blake Wiener speaks to Pascale Meyer and Regula Moser about this new exhibition in addition to the complex interplay between humans and forests.

JBW: The pre-modern history of forest use is quite often one of destruction. The Romans deforested large swathes of the Mediterranean, and in the Middle Ages, population growth came at the expense of forests. There is a showcased platform of medieval and early-modern European woodworking tools with In the Forest. They seemingly provide an indication of the arduous work involved in forestry.

What more can you tell us about these tools? Additionally, would you say that we greatly underestimate the roles in which wood functioned as a natural resource for humankind in premodern times?

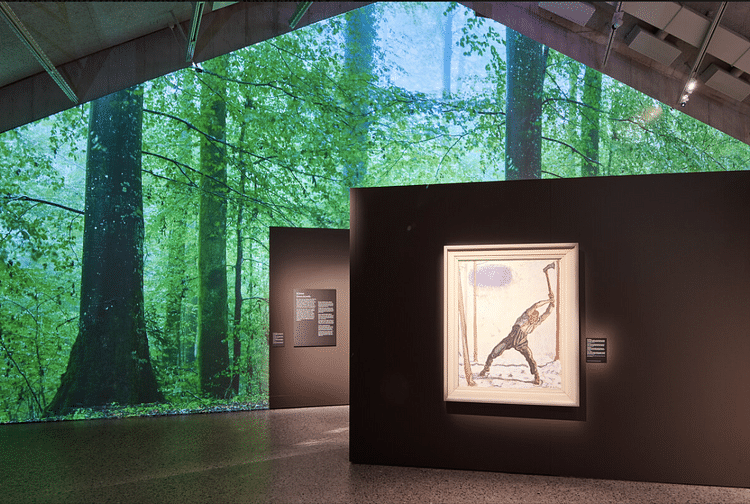

PM: Wood is certainly the central resource in pre-industrial society. Man has been using the forest since time immemorial, that is: cutting it down to harvest firewood and building material. The axe, for example, is one of the oldest tools and has remained one of the most important forestry tools to this day. And even today, forestry work is time-consuming and arduous.

JBW: Humanity’s fluctuating relationship with the forest is also reflected in scores of artistic and literary works. However, depictions in art and literature of the forest are in stark contrast to the real situation: The more the forest is destroyed as a result of industrialization, the more exaggerated and idealized the depictions.

What else can we say about the evolution of this relationship over time? Additionally, which notable works pertaining to this theme are on display within In the Forest?

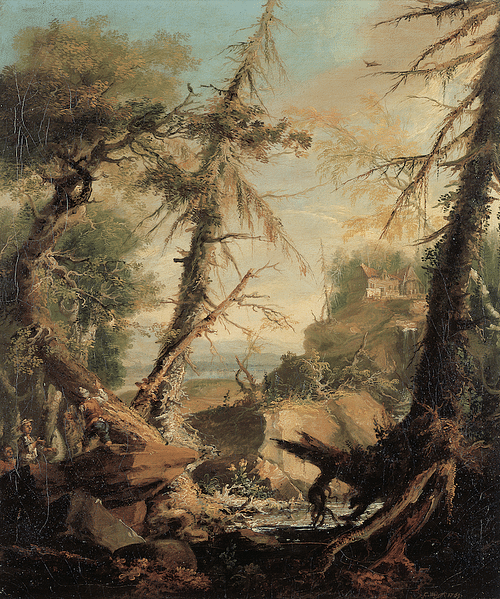

RM: Exactly, especially in Romanticism, art and literature do not reflect real conditions, but contrast them. In works by Caspar Wolf, François Diday or his pupil Alexandre Calame, the forest, and with it the Alpine space, is idealised as a retreat from civilisation. Tourism also made this idyll its own. In the 19th century, painters - probably also as a result of advancing industrialisation - sought a more direct, authentic approach to nature. Perspectives changed, artists left their studios to sketch plein air. This was also the case with the Swiss painter Robert Zünd, who paints the trees as independent protagonists.

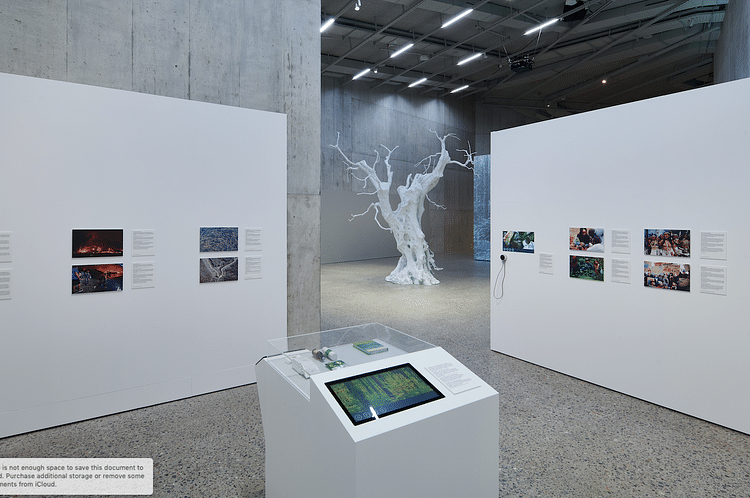

As viewers, we become part of his forest walk. I would argue, however, that the forest has remained a projection, a place of longing, to this day, and that is precisely why there is an enormous potential in the forest. As an example: Jean-Jacques Rousseau wandering through the Jura forests, writing down his musings on playing cards, and then being thrown back into reality by the clatter of a stocking factory. In the 20th century, it is Joseph Beuys who, in 1972, calls out in the forest with 50 art students to save it. With Beuys, an ecological consciousness finds its way into art. Both Beuys and Rousseau practise a critique of civilisation, create a counter-world and find freedom in the forest, albeit an ambivalent one. And it is precisely this ambivalent relationship to nature that artists are still questioning today.

JBW: With the advance of the Industrial Revolution, humanity began to take a more critical look and approach to forest management. In North America, Oceania, and Europe, the first efforts were made to found the first national parks in the late-nineteenth century.

How did this play out in Switzerland, which is today renowned worldwide for its beautiful landscapes and the management of its pristine forests?

PM: The first national park, Yellowstone, founded in 1872, was established as a "recreation area". It was certainly a model for the founding fathers of the Swiss National Park, which is after all the first national park in Europe. But this is where it differs from Yellowstone: the Swiss National Park, which was ceremoniously opened on 1 August 1914, also served research. Left to its own resources, the nature reserve was also intended to provide insights into biodiversity.

JBW: The exhibition shifts from a European focus to encompass some very interesting art from the Gran Chaco plain of South America, which contains the continent’s second-largest forest. Why was indigenous artwork from this region included in In the Forest? What should we draw from the experiences of Gran Chaco’s indigenous peoples with regard to the environment?

RM: The drawings express a deep attachment to the forest and the animals, even though colonisation and sedentarisation changed their lives fundamentally within two generations. Alarmingly, the dry forest of Gran Chaco is being massively deforested: faster than anywhere else. It is precisely in the face of loss and deforestation that their artistic representations of the forest gain in importance.

The artists are self-taught and have only a few years of formal education. They belong to the Nivacle and Guarani communities. The forest is central in their paintings. Animals and trees, hunting and gathering are the most popular motifs. And it is telling that in the language of the indigenous people, forest means 'world'.

JBW: In 1945, the Swiss researchers Armin Caspar and Anita Guidi (1890-1978) traveled to the Amazon region to call attention to the plight of the forests and their inhabitants; 50 years later, the Swiss environmentalist Bruno Manser (1954-2005) journeyed to the region and employed more radical means to fight deforestation and protect indigenous peoples.

Could you briefly tell us a bit more about these colorful personalities and how their importance is reflected within In the Forest?

PM: In 1945 and 1948, the businessman Armin Caspar and the artist Anita Guidi traveled to the territory of the Tukano and Ka'apor in the Amazon. The indigenous population groups were defencelessly exposed to the threatening destruction of their home, the forest, by the settlers and were maligned in Brazil as primitive and dangerous. While Guidi painted people and landscapes, Caspar collected objects that were later shown in exhibitions in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, and throughout Switzerland to draw attention to the precarious situation of the indigenous people. In the process, the gifts Caspar brought with him, for example, the identity-forming feathers, also served as "cultural ambassadors".

From the 1980s onwards, Bruno Manser campaigned uncompromisingly for the protection of the rainforests and the Penan living there. Thanks to his commitment, the issue of tropical timber entered the political agenda in Switzerland. His campaigns drew public attention to the catastrophic ecological and social consequences of deforestation. In Sarawak, however, measurable successes largely failed to materialise.

JBW: On behalf of World History Encyclopedia (WHE), I thank you so much for introducing us to this exhibition and for lending your expertise.

***In the Forest: A Cultural History runs at the Swiss National Museum in Zurich from 18/03/2022 – 17/07/2022.

Pascale Meyer, historian, and Regula Moser, art historian, are curators at the National Museum Zurich.