The Roman army underwent dramatic changes in Late Antiquity. Civil war and external conflicts led to the creation of new legions while existing legions were either split or disbanded. Although there was an increase in the number of legions, these legions were much smaller. Field armies numbered around 1,000 to 2,000, while cavalry units were around 600.

Although sources vary, by the end of the 4th century CE, there were at least 132 legions, plus auxiliaries and various numerii. The Notitia Dignitatum, dating from 395 CE, recognized 180 legions. In contrast, during the time of Trajan (r. 98-117 CE) when the extent of the Roman Empire reached its peak, legions only numbered around 30. Some of the legions of Trajan's reign were still in existence in the 5th century CE – although often serving as border guards – II Traiana, VII Gemina, and IV Gallica.

Late Antiquity

Gillian Clark in her book Late Antiquity wrote that "Late antiquity saw the fall of Rome and the survival of Rome" (1). She viewed Late Antiquity as a conflict of values and a competition for resources, the beginning of which is difficult to define. She maintains that a valid argument could be made for a number of critical times when the defense of Rome was challenged. One might make a case for the reign of the Roman emperor and philosopher Marcus Aurelius (r. 161-180 CE) and his war against the barbarians to the north; another possibility was after the death of Septimius Severus (r. 193-211 CE) and the dawn of political discontent; and lastly, the reign of Constantine I (r. 306-337 CE), the first Christian emperor, is a possibility. However, most historians contend the ideal choice is the transition from Principate to Dominate: the reign of Diocletian (285-305 CE).

Historian Nigel Pollard in his book The Complete Roman Legions wrote that from 235 to 293 CE upheaval plagued the empire "caused by interlinked crises, both within the Roman Empire and on its frontiers" (212), but Diocletian brought a rebirth. Adrian Goldsworthy in his book The Complete Roman Army agrees with Pollard and dates Late Antiquity from the time of Diocletian. "It was within this context of weakening of central authority frequent outbreaks of civil war, and serious problems in many frontier areas that the army of Late Antiquity was forged." (201)

Changes Under Diocletian & Constantine

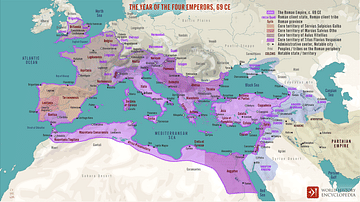

Following years of disorder during the Crisis of the Third Century, Diocletian was able to restore some semblance of peace and stability. He recognized that the vast size of the empire had made governing it difficult. To correct this situation, he created the tetrarchy: a division of the empire into an eastern and a western part, with each governed by an augustus and a caesar. Seeing the need for additional revenue to finance his changes, he reorganized the tax system. With a restructuring of the Roman government and provincial administration came similar changes in the military.

In order to reduce the possibility of revolts in the remote provinces, the emperor doubled the number of provinces from 50 to 100. He then organized these new provinces into twelve dioceses ruled by vicars, who had no military responsibilities. Those duties were assigned to military commanders. Although time would test Diocletian's dream, stability was finally achieved. Pollard wrote that the tetrarchy "formalized the political and military division of the empire that by necessity had characterized much of the second half of the 3rd century" (212). However, despite many of the changes, one controversial issue still plagued the emperor.

Aside from the difficulties with the economics of the empire and border security, Diocletian was concerned with the continuing growth of Christianity. As their numbers increased, the problem continued to grow. Dating from the time of Emperor Nero (r. 54-68 CE), emperors viewed Christianity as a threat to the traditional values of Roman religion. Christians simply refused to pay homage to the Roman gods and were persecuted under Diocletian. It was Constantine’s conversion to Christianity that put an end to much of the oppression and brought tolerance.

With a victory against his last opponent, Licinius, at the Battle of Chrysopolis, Constantine reunited the empire and became the sole emperor. Despite several of the building projects he instituted, Constantine realized that Rome was not the city he wanted for a capital. It was decaying and was no longer a practical site for a capital. Rome had lost its importance. The new economic and cultural center was in the East, and Constantine and his successors would reign from a new capital, Constantinople (New Rome).

External Threats

Besieged by invading barbarians across the west, the Romans met with a number of disastrous defeats. These defeats caused a crucial decline in essential manpower. The number of volunteers had steadily decreased so conscription became necessary. To satisfy this loss, the army turned to the barbarians (mostly Germanic) who had settled on the Roman frontier for recruits. Unlike in the early days of the Principate, Roman citizenship was no longer a requirement to join the army. At one point even prisoners of war were recruited.

Roman leadership had allowed Goths to settle on Roman land but at a price. In exchange for land and provisions, they had to provide soldiers for the Roman army. The Goths eventually resisted and defeated the Romans at the Battle of Adrianople on 9 August 378 CE. The Gothic War (376-382 CE) continued to inflict havoc across the Roman frontier. Finally, in 382 CE, Emperor Theodosius I (r. 379-395 CE) and the Goths came to terms in an alliance that granted lands in exchange for soldiers to serve in the Roman army.

The Roman army became increasingly more dependent on the barbarians, and they could also rise through the ranks. For example, the great commander Stilicho's (365-408 CE) mother was Roman but his father was a Vandal. In time, some of the barbarian recruits would serve under their own tribal leaders. Service time, however, remained the same as in the Principate: 20-24 years.

The Notitia Dignitatum & the Legions

Much of what is known about the legions of Late Antiquity comes from the 40 chapters of the Notitia Dignitatum, an illustrated list of all Roman military and civic officers. It was maintained by a chief notary: a primicerius notariorum. It was divided into two parts – the East (Oriens) and West or (Occidens) – and provided the number of praetorian prefects, the masters of the soldiers (magistri militum), court dignitaries, provincial governors, and the legions under their command.

The exact size of the Roman army during Late Antiquity varies from source to source; however, estimates range from 400,000 to 600,000. With an increase in the number of provinces under Diocletian's revisions, a number of new legions emerged. Some of them came from a split of existing legions while others were newly formed. At the onset of the 4th century CE, there were different kinds of legions:

- Comitatenses or field armies

- Limitanei or border security

- Palatini or imperial legions (named for the Palatine Hill and imperial palace in Rome)

There were only two dozen of the elite palatini legions, the majority were either limitanei or comitatenses. The limitanei manned the field garrisons and provided border security in the provinces. A mixture of legions, cavalry and alae, the limitanei, commanded by a dux, were the first line of defense against an external threat. They were not the farmer-soldier as they have often been portrayed. Many of their names were reminiscent of old legions: III Cyrenaica, XV Apollinaris, and XII Fulminata. However, there were a number of new legions named for a province, an emperor or a god: I Pontica, IV Parthica, I Illyricorum, III Diocletiani, I Maximiana, IV Martia, and II Herculia. Occasionally, units of the limitanei were attached to the field armies, receiving the name pseudo-comitatenses.

While more numerous, the comitatenses, or soldiers of the retinue, were not tied to any one particular province and were often used as mobile strategic reserves, moving where required, and were at the disposal of the emperor. More heavily equipped and with better pay, they were organized differently. Two of the five in the East remained with the emperor commanded by a magister militum, or master of the soldiers, while the remaining three regional armies were stationed elsewhere: one in the East, one in the Balkans (Thrace), and one in Illyricum. Both the limitanei and comitatenses had naval squadrons when necessary.

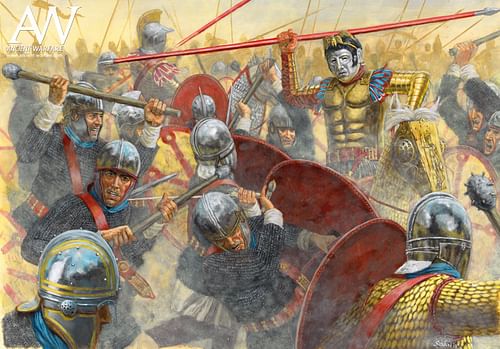

The Infantry & Cavalry

The Roman infantry remained the backbone of the military, but its look had changed. While a Roman legionary still wore armor or a cuirass made of mail and scale, the lorica segmentata had disappeared – there is evidence of legionaries wearing a long mail garment with sleeves and a hood. A few still wore the intercissa-style helmet, and some had a helmet called a spangenhelm, a bowl made of five to six separate segments held together with a metal strap. The legionaries still carried a large oval or round shield. Weaponry included a spear or javelin, with the long spatha replacing the gladius, and they carried small weighted darts. The light cavalry used a javelin and small darts. In battle, the infantry operated a mobile cart-mounted catapult.

Used with greater emphasis than in the past, the cavalry, like the infantry, had undergone a number of significant changes. Taking lessons from ancient Persian warfare and copying the Parthian cataphract, the cavalry saw the advent of the clibanarii, where both the horse and rider wore iron-mail armor, and there were also new units of horse archers. The armor-clad horse and rider were more common in the East. The bulk of the remaining cavalry was primarily used for shock actions. Although the Persians used elephants and camels, the Romans never had much success with them.