In the 13th century, astonishing quantities of spices and silk passed from the Far East to Europe. Exact amounts are not known, but spice popularity in both cuisine and medicine reached its historical peak during the Middle Ages in Europe.

Spices & Silk

The noted expert on medieval gastronomy Paul Freedman tells us that "spices were omnipresent in medieval gastronomy" and "something on the order of 75% of medieval recipes involves spices" (2007, 50). Historical records are filled with references to the copious use of spices among the wealthy in medieval Europe. When William I of Scotland (r. 1165-1214) visited Richard I of England (r. 1189-1199) in 1194, he received among other gifts a daily allotment of 4 pounds (1800 g) of cinnamon and 2 pounds (900 g) of pepper (surely more than he could consume in a day). Lamprey, a popular food in an English medieval castle, was slathered in a peppery sauce. The story goes that King Henry I of England (r. 1100-1135) was killed in 1135 by consuming a huge meal of pepper-smothered lamprey, although food poisoning was probably the culprit. A sauce served at the Feast of St Edward in 1264 was prepared from 15 pounds of cinnamon, 12½ pounds of cumin and 20 pounds of pepper.

Asian spices also played a pivotal role in the medicine of the Middle Ages. Their curative and healthy properties were acclaimed by physicians and the masses, both poor and wealthy. Native plants were also incorporated into the European medical texts, but patients continued to prefer Asian spices if they could afford them. The drugs outlined in herbals and medical texts of the Middle Ages were almost all composed of Asian spices. The widespread belief was that the spices must be more powerful medicines if they came from a distant 'paradise'.

By the Middle Ages, silk from the East had also come to play a central role in European aristocratic lives. As told by Wagner:

Everything and everyone it touched immediately became eminent. Draped over altars or fashioned into curtains, silk separated spaces within a church or a palace. Beginning in the sixth and seventh centuries in Western Europe, saints' relics were wrapped in silk, stored and displayed in elaborate metalwork and jeweled reliquaries … For hundreds of years … silk's qualities of luxury, versatility and scarcity perpetuated its status as a prized material. The luminescence and softness of the fabric always impressed those who saw or felt it … As a commodity, silk was considered at times to be more valuable than gold.

Trade Routes

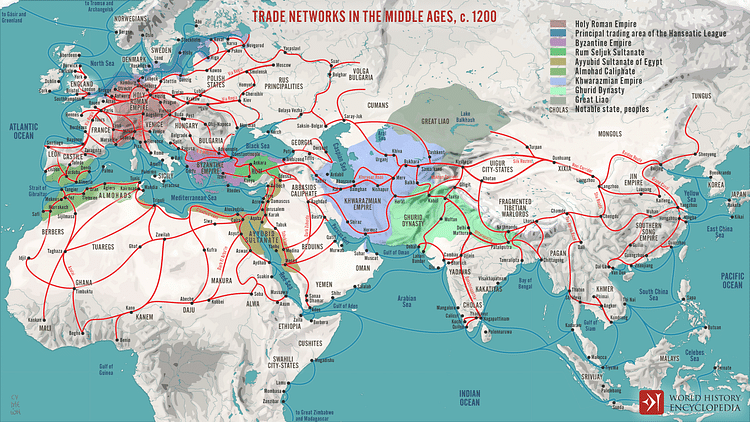

The spices and silk that had found their way to medieval Europe had traveled an incredible distance. In the 13th century, an expansive worldwide trade system was in place that extended all the way from the east coast of China to Western Europe, across both sea and land. The central hinge was the land bridge between the western Mediterranean ports, the eastern outlets to the Indian Ocean, and the Central Asian land routes to China. There were three great paths that wound through the central hinge – two controlled by the Arab world which passed through the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf and the other through the Byzantine Empire which had access to the land routes across Asia.

To the east of the central hinge was the Indian Ocean where Arab traders controlled access to India, as well as the Hinduized Straits of Malacca which were an intermediary for China. The overland trade to Constantinople moved through Mongol China across Persia, the Levant, and Asia Minor. The primary trade route between the Indian Ocean and the Mediterranean passed from Bab al-Mandab, at the southern end of the Red Sea, to Jedda, Mecca's seaport, where goods were moved in vessels that made their way north against the prevailing winds or in caravans that followed the pilgrimage route of the Hijaz to destinations in Egypt and the Levant.

The Persian Gulf portal to Indian Ocean trade was at Ormuz, which had long served as a vital link between the Persian world and the Indian Ocean. In his visit to Ormuz in 1272, Marco Polo wrote:

And I can tell you that merchants come here by ship from every part of India, bringing all sorts of spices, precious stones and pearls, silk and gold fabrics, elephants’ tusks, and many other products. In this city they sell these goods to other merchants, who then distribute them throughout the world, selling them to others in turn. (66)

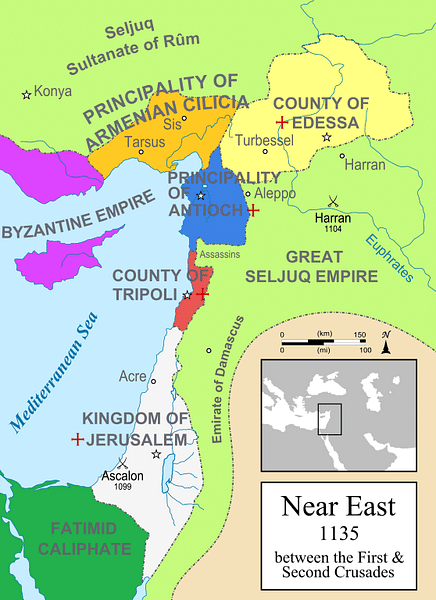

Crusader States

For centuries, the Christians held tenaciously through the Crusades to a foothold in the largely Muslim Middle East. In spite of the constant warfare, the Italian merchant cities maintained active trade with many ports in the Levant. The larger cities had become active mercantile centers with traders in residence from Arabia, Iraq, Byzantium, North Africa, and Italy. Specialized markets arose where locals and foreigners could purchase a wide array of goods from silks and spices to basic foodstuffs, leather goods, cloth, furs, and other manufactured goods. To get to and from the centers of trade along the eastern Mediterranean, Christian, Jewish, and Muslim traders moved remarkably freely across hostile lands.

The great Muslim chronicler Ibn Jubayr who traveled in the Middle East during the 12th century wrote:

One of the astonishing things that is talked of is that though the fires of discord burn between the two parties, Muslim and Christian, two armies of them may meet and dispose themselves in battle array, and yet Muslim and Christian travelers will come and go between them without interference. (Broadhurst, 300–301)

India

India was the epicenter of global trade. On the Malabar and Coromandel coasts, colonies of traders from all over the world came together to trade cotton and silk, spices and perfumes, as well as gold, silver, and ivory. From India came pepper, precious stones, jewelry and cotton fabrics. Indian traders went out widely across the Indian Ocean in search of goods and brought back exotic luxuries from a wide mix of cultures that made everyone prosperous.

Among the most important mercantile cities were Hindu-controlled Calicut (today Kozhikode), Cannanore (Kannur), Cochin, Quilon (Kollam), Muslim Goa, and Cambay (Khambhat) of Gujarat in the north-western corner of the Kathiawar Peninsula. Cambay was the home of probably the world's most widely-traveled merchants. They settled all over the Indian Ocean and sailed widely across the Indian Ocean from Aden to Malacca.

Calicut was by far the most important entrepôt of India, and for centuries it was a primary destination of all Indian Ocean traders from Aden, Ormuz, Malacca, and China. It also came to be renowned for what the European traders called 'calico' cloth, from which it derived its English name. Calicut was ruled by a powerful Hindu hereditary leader called the zamorin, who cooperated closely with Muslim traders to facilitate trade. The other great Indian spice cities of the Malabar Coast (Cannanore, Cochin, Quilon) were unhappy feudal vassalages of the Zamorin of Calicut and paid tribute to him. The Zamorin of Calicut would prove to be a formidable opponent in Portugal's later attempt to block Muslim commerce in the Indian Ocean.

The early Portuguese chronicler Duarte Barbosa wrote of Goa:

The city was inhabited by Moors, respectable man and foreigners and rich merchants; there were many great Gentile Merchants and other gentlemen, cultivators, men at arms. It was a place of great Trade. It has a good port which flock many ships from Mekkah, Aden, Hormuz, Cambay Malabar Country. The town was very large with good edifices handsome streets surrounded by walls and towers. (Fernandes, 284)

Indonesian Markets

By the 13th century, the city of Malacca (Melaka) along the Strait of Malacca on the Malay Peninsula also was one of the most important centres of world trade. It was the great international clearing house for pepper, nutmeg, and cloves, where East met West. The history of the region as a trade center began c. 300 BCE when small Hindu kingdoms sprang up on Java and Sumatra under the influence of traders from India. These were joined by Buddhist ones in the early centuries CE. The powerful Buddhist kingdom of Srivijaya arose on Sumatra and took control of most of the Malay Archipelago until it was conquered in 1290 by the Hindu Majapahit Empire from Java. The Majapahit Empire would become so powerful that it refused to pay tribute to China and was able to defeat a force sent by Kublai Khan (r. 1260-1294) of the Mongol Empire who also ruled China.

An important stopover for merchants on the way to and from Malacca was Buddhist Ceylon (today's Sri Lanka), where the world's finest cinnamon could be obtained along with gems, pearls, ivory, elephants, turtle shells, and cloth. Ships from across the world came to Ceylon for its native products and goods brought from other countries for re-export. The islanders also sent their own ships to foreign ports. The most important items imported were horses from India and Persia, and from China came gold, silver and copper coins, silk and ceramics. There were numerous bays and anchorages dotted along the coast of Ceylon, which provided calm harbors and facilities for ships.

On the fringe of the Indonesian archipelago were the Moluccas or Spice Islands, the world's only source of cloves, nutmeg, and mace. Cloves were found exclusively on only a few tiny, volcanic Maluku Islands of Indonesia, while the nutmeg tree is native to sheltered valleys on the hot tropical Banda Islands. These islands were only visited by merchants from Java and China. Arab and Gujarati sailors relied on Indonesian merchant sailors to deliver the spices to Malacca, where they then traded for them and dispersed them across the rest of the Indian Ocean.

Chinese Sea Routes

In the 12th century, China was the most advanced economy on earth and was the most dynamic force in Asian trade. The city of Hangzhou had 1 million residents, including a large merchant class. The Chinese plied the Indian Ocean with fleets of ocean-going merchant junks, 30 m (100 ft) long and 7,5 m (25 ft) wide, carrying 120 tons of cargo and 60 crew. Those ships visited Indonesia, Ceylon, and the west coast of India. Under the Southern Song Dynasty (1127–1279), China enjoyed a large trade surplus.

While exporting the world's highest quality textiles, ceramics and metal goods, China imported a narrower range of products – foreign woods, resins and spices, most from Southeast Asia, some from the middle east … The imports of fragrances were extremely because all social levels consumed them. (Hansen, 219)

When all of China was taken over by the Mongols in 1279, the trade with Southeast Asia continued to boom, dealing in ivory, rhinoceros horn, crane crests, pearls, coral, kingfisher feathers and turtle and tortoise shells.

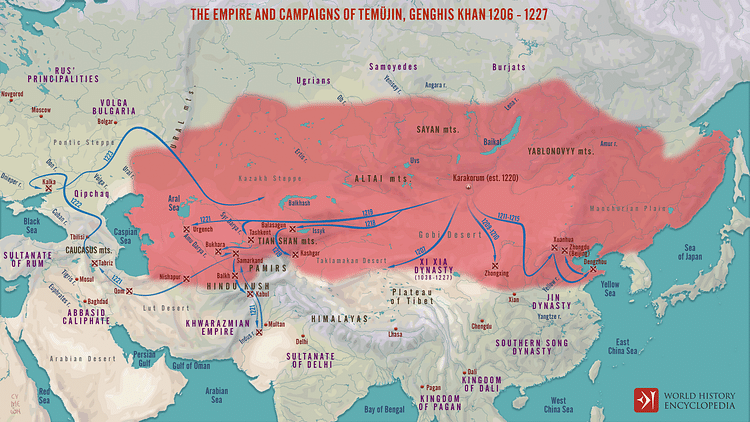

Mongol Land-based Silk Routes

Over the centuries, the amount of movement along the Silk Road rose and fell depending on the politics of the kingdoms through which it passed. The coming of Genghis Khan (1206-1227) and the Golden Horde blew new life into trade along the ancient Silk Routes in the 13th century. After the Mongol conquests, exotic goods such as silk, porcelain, and spices began to move freely along the Silk Routes towards Europe. The total length of the Silk Road was about 10,000 km (6214 mi), of which approximately 3000 km (1864 mi) were inside China's territory.

Trade activity along the Silk Routes was not only revived by the Mongols but expanded to unprecedented heights. The Mongols were strong advocates of open trade, allowing products from China and Southeast Asia to freely make their way to Eastern Europe and the Middle East, and vice versa. Marco Polo's (1254-1324) father Niccoló and his uncle Maffeo embarked on their first journey east in 1260, and Marco began his own epic trip in 1271. To encourage international trade, foreign merchants were often given tax exemptions, loans, and guaranteed safe passage along the Silk Road. The Mongols also actively encouraged trade by establishing garrisons along the Silk Road which were patrolled by Mongol soldiers and served as waystations and rest stops for travelers.

European Trade Networks

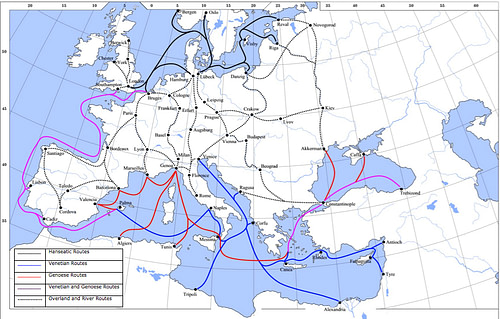

The linkage to Europe from all of the worldwide markets was through Italy. Throughout most of the medieval period, the Italian city-states of Venice, Genoa, and to a lesser extent Pisa, jockeyed to move commodities from the Asian market to Europe via the central hinge. Venice dominated trade in the eastern Mediterranean from the 10th to the 12th century as an affiliate of the Byzantine Empire. In the 13th century, its power grew even greater when it abandoned its long-time partner during the Fourth Crusade, supported the occupation of Constantinople, and took control of most of the Adriatic ports of the Byzantines. To this bounty was added Corfu in 1207 and Crete in 1209. This gave the Venetians a trade network that extended from the Golden Horn of Constantinople to the major ports in Syria and Egypt, and access to all the spices flowing into the Middle East from Southeast Asia and India.

The location of Venice was perfect to control trade with the markets of the Black Sea, Levant, and Egypt. As Krondl describes:

Venice is positioned at the very northwest corner of the Adriatic, the largest gulf in the Mediterranean and just across the Alps from the German-speaking lands. From Venice it is more or less a direct shot down the eastern Adriatic coast, skimming mainland Greece, past the island of Crete, and then straight down to Egypt. This voyage is easily the most direct path between the spice emporia of the orient and the silver mines of the heart of Europe. (44)

Another trading power emerged in the eastern Mediterranean in the 12th century: the Catalonian trade network. It encompassed Catalonia, Mallorca, and Valencia in north-eastern Spain and was centered in Barcelona. The savvy Catalonian merchants carefully analyzed potential markets and encouraged the production of those agricultural and artisanal products that were most likely to be accepted in foreign markets. They started with wheat, oil, honey, wine, Muslim slaves, weapons (very high-quality swords and knives), and cordovan leathers. Over time they added to their offerings saffron, dried fruit, coral, woolen cloth, ceramics, crafted hides, glue, tallow, and glass objects. Their trade networks extended to France, Italy, North Africa, the Levant, and along the Atlantic coast including Andalusia, Portugal, England, and Flanders.

In the 12th century, a great trading league called the Hanseatic League (Hanseatic Union, Hansa or Hanse) also emerged in Europe that linked all the major cities surrounding the Baltic Sea and the North Sea. The league grew steadily in power throughout the 13th century.

The Hansa was comprised of almost 200 maritime and interior cities (along rivers). It extended from Bruges and Ghent in Flanders and London in the west to the Republic of Novgorod in western Russia and Tallinn on the Gulf of Finland in the east; from Bergen in the north to middle Germany in the south. [Hansa activities even] extended to Venice … where German merchants lived and warehoused their goods." (Liggio, 134)

Conclusion

Trade and commerce in the medieval world developed to such an extent that even relatively small communities had access to weekly markets and, perhaps a day's travel away, larger but less frequent fairs, where the full range of consumer goods of the period was set out to tempt the shopper and small retailer. As the High Middle Ages progressed, many overland trade routes came to link the north-western European cities with the Italian mercantile states. Exotic goods were transported laboriously up the Po and Rhône valleys into central and northern France, where they were brought together with those coming south-west from Flanders and the North Sea. The maritime trade routes of the North Seas came to be fully joined with the Mediterranean ones.

International trade fairs became important in the 12th and 13th centuries at the confluence of these trade routes in France, England, Flanders, and Germany. The most famous were held in the towns of Champagne, in north-east France. Here Northern European merchants brought furs, wool, and the spices of the Far East. Goods moving from Italy were carried there by caravans of pack mules, crossing the Alps through the Mont Cenis Pass, along the ancient route called the Via Francigena. It took a month to make the trip from Genoa to the French fair cities. In the 13th century, the world was completely connected as a global economy. Vast quantities of goods were passing through all the empires of the world, by land and sea. Trade was essentially unfettered by country boundaries and ethnicity.