Ancient Greek clothing developed from the Minoan Civilization of Crete (2000-1450 BCE) through the Mycenean Civilization (1700-1100 BCE), Archaic Period (8th century to c. 480 BCE) and is most recognizable from the Classical Period (c. 480-323 BCE). The simplified fashion of the later periods recommended Greek garments to other cultures who adopted and used them widely.

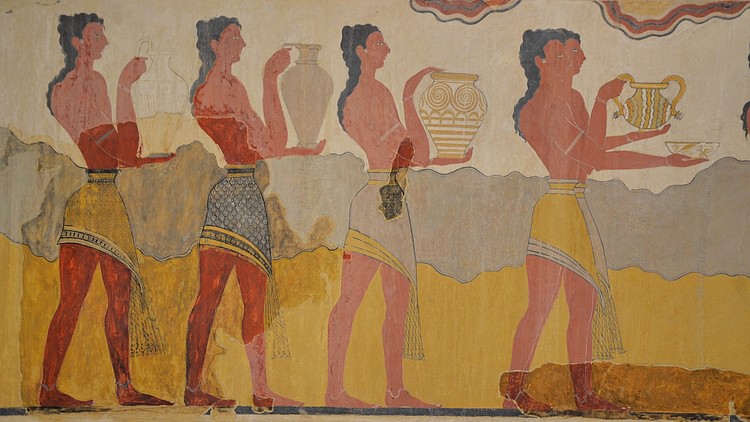

Generally speaking, most of what is known of ancient Greek clothing reflects only the upper-class as they were most often depicted in artworks, and these preserve the kinds of clothing worn. In the Minoan Period, upper-class men of the court seem to have dressed primarily in loincloths, a cloak, sandals, and sometimes a headpiece while women were more completely covered save for the breasts which were exposed. The Mycenean fashion sense was influenced by the Minoan, but during the Archaic Period, clothing was simplified and remained so through the Classical Period.

The types of garments were essentially the same from the Archaic through the Classical periods:

- Strophion – a cloth band which served women as a bra

- Perizoma – a loincloth worn by men and women as underwear

- Chiton – a tunic of two different styles, Doric and Ionic, worn by both sexes

- Chlamys – an outer garment used as a short cape or cloak, worn primarily by men

- Peplos - a garment worn mainly by women over a chiton or instead of one

- Epiblema – a shawl worn over a chiton or peplos by both men and women

- Himation – a larger outer garment worn as a long cape or cloak by both sexes

These were all uncut, unsewn, pieces of cloth – linen or wool – which were arranged on a person in different ways to produce different effects. The primary garments were simply cloth squares, cylinders, or rectangles, which were wrapped or draped on a person and then fastened with pins, buttons, or brooches to hold them in place. The ease of manipulating the cloth into a garment, which could then be arranged in different styles, meant one could use a single piece of fabric multiple times to create different outfits.

Adding to or taking away from the basic chiton through additional clothing, different jewelry, and other accessories, created easy-to-wear, comfortable clothing which was noticed and appreciated by neighboring cultures. This paradigm of dress continued through the Hellenistic and Roman periods and influenced both men’s and women’s fashions in the Middle Ages and up through the present day.

Minoan & Mycenaean Fashion

Everything known of ancient Greek clothing comes from depictions in artwork and Greek literature of the time, and this begins with the Minoan Civilization which scholars have divided into the time periods of Early Minoan (EM), Middle Minoan (MM), and Late Minoan (LM), which are further divided into subperiods of each. Some of the earliest statuary and artwork comes from the Middle Minoan period of MM I (c. 2100-1900 BCE) through MM III (ending c. 1600 BCE) depicting human figures clothed in the dress of the time.

Minoan men are seen in loincloths, cloaks, and sandals but seem to have gone mostly barefoot, especially indoors. Men are also depicted wearing armbands, wristbands, and jewelry. They wore their hair long and loose but held in place by a headpiece, sometimes a feathered headdress or hat, and their clothing was brightly colored red, yellow, black, and purple. Purple dye was produced on Crete through harvesting of the murex shell, and dyed garments of any color were quite expensive, but none more so than purple cloth.

Artifacts and depictions from MM I show men in loincloths, male athletes either dressed the same or naked, and women in bell-shaped skirts, tight bodices which lifted and exposed the breasts, jewelry, and headpieces. The same kinds of pieces from MM III show the same basic style and pattern, but with greater detail. One famous example of this is the figure known as the Snake Goddess or Attendant, dated to MM III, and thought to depict a deity or a member of her clergy in naturalistic form, meaning, in this case, wearing the kind of clothing an upper-class woman of the time would have worn. Art historian and scholar John Griffiths Pedley comments:

[The Snake Goddess or Attendant figurine] is 13 ½ inches (34.5 cm) tall and is one of the largest surviving examples of Minoan sculpture in the round. She wears a bell-shaped, flounced skirt, a tight belt, and a short apron; her breasts are bare. Snakes curl down and along her arms and around her waist and shoulder while another circles her lofty hat. The other figures [found with her] display similar posture, proportions, and clothing, brightly colored with shades of red, blue, and green. (49)

The Mycenaean Civilization, the latest of the so-called Helladic Period of mainland Greece, is also divided by scholars into different periods and works from the Early Helladic Period (c. 3200 - c. 2000 BCE) through the Late Helladic (c. 1550 - c. 1050 BCE) show similar styles as the Minoan. A terracotta female figure from Keos dated to the Late Helladic II Period (c. 1450 - c. 1400 BCE) shows a woman in the same bell-shaped skirt, bare breasts, and a similar bodice. It is possible this is a copy of the Snake Goddess figurine but could also be an original work of its time.

Men’s clothing shows some difference from the Minoan Period, however, as seen in a statue depicting a young man in the same sort of loincloth as the Minoans but wearing a different kind of headpiece and a high kilt. A wall painting from the palace at Pylos dated to Late Helladic III (LH IIIB, c. 1300 - c. 1200 BCE) shows warriors in battle wearing the chiton tunic fighting others in kilts, helmets, and knee-high boots. The Warrior Vase, currently in the National Museum at Athens and dated to the same period as the painting, depicts Mycenean warriors in the same helmets, kilts, and boots but with body armor and is considered a realistic depiction of the soldiers of the time.

Archaic Simplification & Classical Style

The Minoan and Mycenaean cultures both give evidence of brightly colored and intricately tailored clothing, especially for women, but this kind of fashion and the technology that produced it did not survive the Bronze Age Collapse which brought down the Mycenaean Civilization. Pedley notes:

With the destruction of the Mycenaean palaces went the social system of which they were the centers. Kings, subordinates, scribes, and the knowledge of writing all disappeared. With them was also lost the knowledge of masonry and construction using cut blocks, of wall painting, the working of ivory, precious metals…all the sophisticated achievements of the Greek Bronze Age vanished. (105-106)

After the so-called Greek Dark Ages (c. 1100-700 BCE), the civilization began to revive in the Archaic Period, but the fashion had changed significantly. Clothing was now a single piece of cloth draped around a person and then folded and held in place according to personal taste. Comparing statuary and paintings of Minoan and Mycenean women with their belled skirts and bodices with later images of Greek women wearing the peplos, the simplification of style is apparent, and it is thought that the knowledge of how the earlier clothing was made was lost.

In the Archaic and Classical periods, the manufacture of clothing was considered women’s work in ancient Greece, especially the spinning of wool, although male merchants predominantly sold the finished product. Prostitutes frequently spun wool in their downtime, however, and women generally sold it for extra money. Garments were frequently made at home in the women’s quarters though there were professional weavers and dyers. Wealthy Greeks could afford colorful clothing, which was quite expensive, while the lower class usually wore only white chitons or loincloths.

Garments, Brooches, & Footwear

Garments were made of linen or wool. Linen was more expensive and only available to the upper class while spinning wool was widely practiced by women in ancient Greece and was used to make clothes for all classes and every age group. Dyed clothing also was only available to the wealthy as were garments decorated with prints and weights at the bottom to make them drape across the body and hold securely.

The clothes of the upper-class were brightly colored, even if only along the borders. The modern-day claim that the color blue was unknown in the Mediterranean only applies after the Bronze Age Collapse. Egyptian and Minoan art both show blue in use over an extended period but knowledge of how to make blue pigment is not evident in the Archaic Period. No blue garments are suggested by Greek art or literature though purple was still popular, and many other colors were regularly used.

There were four basic garments in an ancient upper-class Greek wardrobe besides the perizoma (loincloth/underwear) and strophion (bra). There is no evidence of the Minoan bodice, and the perizoma appears less graceful than the Minoan loincloth. These four were:

The Chiton: This was a simple, white tunic which could be an undergarment or one’s daily public outfit. It was a cloth cylinder one stepped into which was held at the shoulders by brooches or pins and bloused at the waist by pulling it over a zone (pronounced zoh-nay), a belt of leather or cloth. The chiton is defined by two styles, Doric and Ionic. Scholar Iris Brooke explains the difference:

[The Doric and Ionic designations] divides them according to two of the main orders in architecture, which were developed by the two leading racial groups, Dorian Greeks and Ionian Greeks. The Doric was severely simple; the Ionic a trifle more complicated, as indeed the Ionic is in every sense. The Doric chiton [was] a straight, unsewn piece of material, wrapped around the body and pinned on the shoulders. The material could be of almost any width, from a yard up to about three yards, but was probably not wider than three yards. The Ionic chiton is much fuller than the Doric and is sewn up like a vast un-shaped skirt. To put it on, one of the open edges should be pinned at regular intervals leaving a slightly larger interval for the head to go through. The hands are then put through between the last pin at each end and the fold in the fabric. This will form a sort of long sleeve with the pins decorating the arm and permitting the material to fall open between them, showing the bare arm. It can be girdled as desired [and] the girdle itself will help pleat the skirt. (Nardo, 42-43)

Men, women, and children wore the chiton, but women and girls seem to have been far more particular about how the garment looked on them. Male chitons usually went only to the knees and were belted. This was the typical outfit of craftspeople, prostitutes (male and female), warriors, athletes, and slaves who were not engaged in manual labor (who only wore loincloths). Slave chitons seem to have been the Doric design.

The Chlamys: Some men (more than women) wore a chlamys over the chiton. This was a short cloak one wore either as a kind of cape, fastened at the neck and falling over both shoulders down the back or over one shoulder and fastened on the other. The chlamys was mainly worn by soldiers, messengers, and upper-class servants.

The Peplos: This was a large square piece of cloth which could be worn by a woman or a man, instead of a chiton or over it, and was more often worn by women. Typically, an upper-class woman would wear a chiton undergarment with an ornamented peplos over it which fell to the feet and sometimes trailed behind. Depictions of aristocratic Greek women in film often show them wearing what appears to be a multi-layered robe, decorated at the border with color, which would be a peplos over a chiton. One’s status was made clear to all by the amount of clothing one wore because garments, especially dyed or ornamented, were expensive. Statuary of the Classical Period frequently depicts goddesses and noble ladies wearing the peplos and chiton or just the peplos. The caryatid columns on the porch of the Erechtheion on the Athenian Acropolis are of women wearing the bloused peplos.

The Epiblema: Some women would ornament their outfit with a shawl, sometimes a simple affair to provide warmth or a decorated piece of finery. A finely woven shawl, especially if it were dyed or patterned, was a not-so-subtle way to show off one’s wealth and men would also accessorize an outfit in this way.

The Himation: Worn over a chiton, peplos, or both by men and women, the himation was a great cloak of five yards long and about one yard wide which was usually dyed and ornamented. Brooke describes the garment:

The ends were decorated and quite often had a fringe or tassels, or some small weight of beads attached at the corners so that in movement the weight swung away from the body and emphasized the pattern of the border design. It was worn, as all the garments were, by both men and women. There was no distinctive garment peculiar to either sex, though a version of the himation with the lower edge woven in points and the upper edge pleated on to a band worn under one arm and fastened on the opposite shoulder seems to appear far more frequently on women than it does on men. This highly decorative pleated himation is nearly always represented as one of Athena’s garments, also those of queens and other noble women. Its shape lends itself readily to sculpture and the borders of the decoration make a fine pattern on the figured vases. (Nardo, 45)

The himation is the cloak one sees Greek generals, kings, queens, and nobles wearing in films and video games. It became well known in the modern age after the release of the film 300 in 2006 as King Leonidas I is shown wearing the red himation. As with the chlamys, the himation could be worn as a cape, a robe, or a blanket and was especially valued in the cold Greek winters as it was made of thick wool which held one’s body heat.

All of these garments were secured on a person through various fasteners, either pins, buttons, or brooches. The brooches could be quite ornate and, in the Roman Period, were known as fibulae which became a kind of artwork in their own right. The girdle also helped secure a chiton or peplos at the waist as did the belt known as the zone. Accessories included a wide-brimmed hat (the petasos) for men and a peaked hat, sometimes with a flat brim, for women.

Men and women wore sandals, slippers, shoes, and boots. Philosophers were famous for wearing a simple chiton, unornamented himation, and the most basic leather shoes. The stereotypical image of the Greek philosopher, not idealized as in the case of Socrates or Plato but the average teacher of philosophy, is depicted with the poorest of shoes, the obligatory staff, and an old cloak. Soldiers wore boots or sandals with shin protectors known as greaves. Most Greeks went barefoot, especially at home, and athletes, especially, were known to reject footwear. Athletes also had no use for most of the above garments both in their training and in competition as it was thought one performed better naked.

Conclusion

The clothing of the Greeks influenced the fashion sense of the Romans who adopted many of these same garments for themselves. Scholar Don Nardo comments:

Most of the clothes worn in ancient Greece (as well as in numerous other Mediterranean lands, which copied Greek dress to one degree or another between about 600 B.C. and A.D. 200) fell into a few simple, basic forms. Each could be worn in a number of different variations and styles, depending on the situation and/or the wearer’s personal tastes. (42)

Unlike the Minoan and Mycenaean fashion, which seem, for women anyway, to have been far more complex, the simplicity of Archaic and Classical Greek garments recommended them to other cultures in the region and were adopted by still others later on. Pleating techniques of the ancient Greek himation, whereby the cloth was gathered, folded, and pressed to create straight lines down the back to accentuate height, were later used in Europe during the Renaissance for the capes and cloaks of the nobility.

Ancient Greek clothing and style even influence fashion in the present day. Women’s evening gowns frequently follow Greek patterns, and the hourglass figure which has come to be associated with feminine beauty was first recognized and accentuated by the Greeks through women’s clothing. Male fashion emphasizing height, strength, and power was also first standardized by the ancient Greeks who believed males were superior to females and should look the part. However that may be, the ease of use and unisex aspect of Greek clothing made it instantly appealing to neighboring civilizations. Greek garments were easily adaptable to various climates and cultures and the basic forms of these clothes still function as models in fashion over 2,000 years after they were first created.