The impressionist exhibitions in Paris through the final quarter of the 19th century were organised by a group of avant-garde artists who struggled to have their innovative works accepted by the art establishment. Although ridiculed by many critics and with only poor sales, the exhibitions gradually established a new means through which the public and collectors could meet new art.

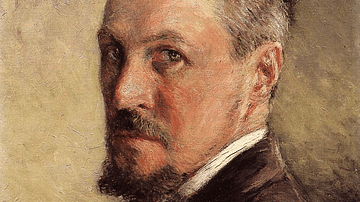

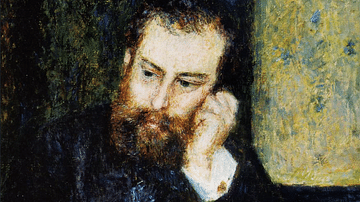

The impressionist exhibitions challenged the monopoly of the Paris Salon on showcasing art and allowed the impressionists to select what they considered their finest works. The group of independent artists who organised the exhibitions included Claude Monet (1840-1926), Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919), Paul Cézanne (1839-1906), Edgar Degas (1834-1917), and many other now-world-famous names. Backed by art dealers and wealthy collectors like Gustave Caillebotte (1848-1894), the exhibitions gradually became more successful in terms of covering their costs, attracting less hostile criticism, and sales of artworks.

The eight independent impressionist exhibitions and their locations were:

First Exhibition: April-May 1874 - Ex-photographic gallery, Boulevard des Capucines

Second Exhibition: April 1876 Galerie Durand-Ruel, Rue Le Peletier

Third Exhibition: April 1877 - Private apartment, Rue Le Peletier

Fourth Exhibition: April-May 1879 - Avenue de l'Opéra

Fifth Exhibition: April 1880 - Rue des Pyramides

Sixth Exhibition: April 1881 - Photographic gallery, Boulevard des Capucines

Seventh Exhibition: March 1882 - Salles de Panoramas hall, Rue Saint-Honoré

Eighth Exhibition: May-June 1886 - Rue Laffitte

The Paris Salon

Fine art produced in France really had only one space to be showcased to the public, collectors, and possible future commissioners: the Paris Salon. Run under the auspices of the French Academy, it monopolised art from 1667 onwards. The problem with the Salon was that every artist with any ambition sent their works to be exhibited in the biannual (and later annual) exhibitions which, of course, had limited wall space. Consequently, a jury of art experts examined submissions and selected what would be shown and in which part of the exhibition hall. Many young artists were rejected, especially if they did not conform to the artistic conventions of the day. Even if an avant-garde artist did manage to be selected, his work would more than likely be shown in a disadvantageous spot like very high up on the wall or in a darker corner. The Salon showed around 4,000 works and so it was quite easy to have a painting lost in the crowd. Further, works which were rejected by the Salon were sent back to the artist with a red letter ‘R’ stamped on the back of the canvas. This was both a humiliation for the artist and an almost certain guarantee that nobody would ever buy the work.

Many young artists, the impressionists included, did still try to have works accepted by the Salon despite the difficulties. The prestige of being shown, the publicity in the press, and the opportunity to find a wealthy patron were all too tempting opportunities not to chance. However, the impressionists – with their colourful canvases, unusual subjects, and revolutionary brushwork – eventually realised that the only way to get their works consistently to the public was to organise their own exhibitions.

The First Impressionist Exhibition

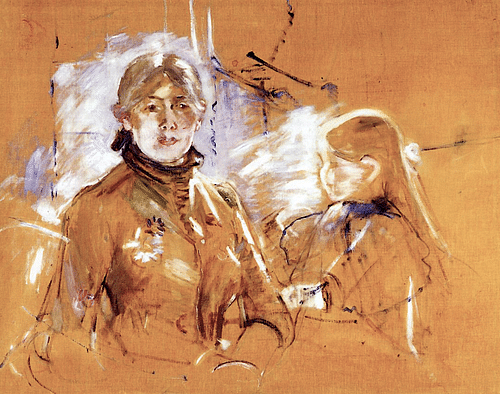

The group of young artists who became known as the impressionists (although not all were, and those who were varied in style greatly) knew each other because they frequented the same fashionable cafés and restaurants in Paris. From the 1860s, they met in such places as the Café Guerbois and others in the Batignolles area of Paris. Besides Monet, Degas, Renoir, and Cézanne, there was Berthe Morisot (1841-1895) and Camille Pissarro (1830-1903). There were literary men, too, such as Émile Zola (1840-1902). The group included new members every so often, and some left over the years, but they collectively became known as 'the Batignolles' after the quarter they most frequented. A few attempts had already been made to try and organise a joint exhibition, but these had never quite materialised into reality. By 1872, though, the group, reassembled after the disruption of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, was determined to press on with the idea.

As they became more formally organised to put on their first exhibition, the group called themselves the Anonymous Cooperative Society of Artists (Painters, Sculptors, Engravers, etc.), and in December 1873, they drew up a charter to outline their aims. Not all of the group wanted to participate in an independent exhibition. Edouard Manet (1832-1883) was a notable absentee as he had already had his work exhibited in the Salon and thought that going independent might jeopardise his future chances there. However, the planned show still contained a wide number and variety of artists, and each would receive an equal share of the profits.

The exhibition was held in the ex-gallery of Nadar, a photographer sympathetic to the impressionists. The space was in Boulevard des Capucines, and the entry ticket was a modest one franc (a catalogue cost 20 centimes). Around 175 works were on display by 30 artists. It was not a competition like the Salon with medals awarded for the best works. All works were equal, lots were drawn for hanging positions, and everything was for sale if not already owned by a collector. Pissarro had the idea to present his canvases in less-distracting plain white frames, a marked contrast to the heavily gilded frames seen in the Salon's offerings. Another innovation was to show the works alone or at most with one above another (the Salon had paintings in columns of four making the top row very difficult to see properly).

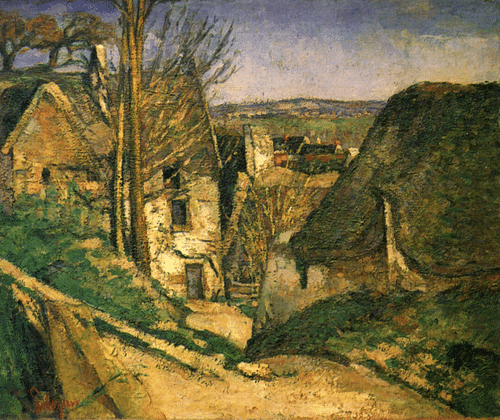

The first day attracted 175 visitors, not exactly close to the 10,000 daily visitors at the Salon. After the month-long show closed its doors, the 4,000 total visitors had not paid enough money to cover the exhibition costs. People had laughed and made fun of many of the paintings. Some visitors were visibly angry at this art they could not or would not understand. There was even a danger of some canvases being physically attacked, as one artist noted in a letter to Dr. Paul Gachet, who had bought several of the works on display: "I'm standing guard over your Cézanne, but I can't guarantee anything; I'm afraid it will be returned to you in shreds" (Bouruet Aubertot, 189).

Critical Reaction

"The critics are eating us alive," Pissarro wrote in a letter to a friend in 1874 (Bouruet Aubertot, 187). In reality, the idea that all critics were against the impressionists is something of a myth. Many reviews were neutral, some even positive, especially in the more radical press. There were indeed some very harsh reviews, though. Most critics found fault with the obvious brushwork of the artists, taking this as a sign of hurried and unfinished work. They disliked the lack of draughtsmanship and vague forms. The use of certain colours was highly unconventional, and the choice of subjects seemed bizarre. Some of the more extreme reactions from critics in the press included: "wallpaper in its early stages is much more finished than that" (Roe, 129) and "…these are paint scrapings from a palette spread evenly over a dirty canvas. There's neither head nor tail, top nor bottom, back nor front" (Bouruet Aubertot, 189).

Most significant of the critics was Louis Leroy, since it was he who, after being left decidedly unimpressed by a Monet painting titled Impression, Sunrise – a view of Le Havre's industrial harbour with a fierce orange sun reflected in purple waters – had labelled all of this perplexing exhibition's art as 'impressionism'. For Leroy, this was a derogatory term. Another significant critic was Albert Wolff of Le Figaro, who singled out Pissarro for particular criticism, stating that "in no country on earth will you find the things he paints" (Bouruet Aubertot, 216).

The Second Exhibition

The Anonymous Cooperative was undeterred by the lack of financial and critical success of the first exhibition, and within two years they were back. The event, which showcased over 250 works by 20 artists, was financed by the engineer Ernest Rouart. The venue this time was the gallery of the art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel, another important friend of the impressionists. Some of the artists had changed but, alas, the overall success rate had not, despite collectors and supporters like Victor Chocquet acting as a guide for each visitor. Monet's The Japanese Girl was popular but viewed as too commercial by some of his peers. The sensation was undoubtedly Caillebotte's The Floor Planers with its highly unusual view of labourers stripped to the waist stripping a wooden floor. Many visitors still came for the giggle and to point disapprovingly at such works as Degas' In the Cafe, which showed what might be construed as a prostitute drinking absinthe. The exhibition at least this time made enough money to cover the costs, but the dividend for each participant was a mere 3 francs.

There were a few positive reviews in the radical press, but the mainstream journals had another field day of printing negative hyperbole. Wolff was there again to leave his acid comments: "a ruthless spectacle is offered…five or six lunatics…among them a woman…a group of unfortunate creatures stricken with the mania of ambition…" (Howard, 84). Despite all the criticism, though, the artists remained optimistic and they had certainly gained publicity, as Berthe Morisot confirms in a letter of 1876: "Anyway we are being discussed and we are so proud of it that we are all very happy." (Howard, 74).

The Third Exhibition

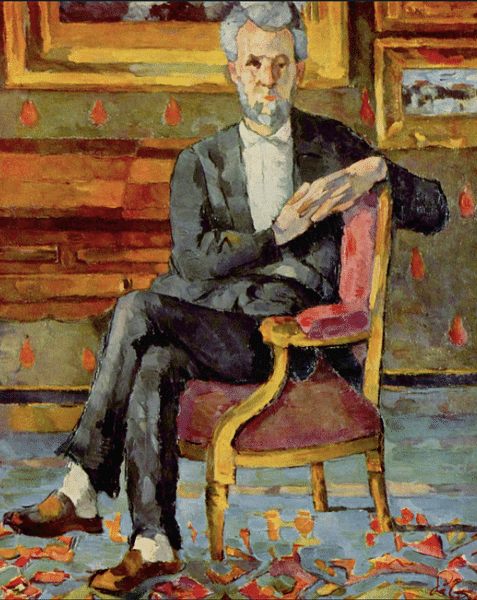

Gustave Caillebotte largely funded this exhibition, and he hired an empty and spacious five-room apartment for the purpose. At this exhibition, Degas made the rule that an artist could not submit to the Salon and the independent exhibition. As a result, perhaps, this time there were fewer artists involved, only 18, who showed collectively 230 works. Important canvases included Monet's studies of Gare Saint-Lazare, Renoir's Dance at Le Moulin de la Galette, and Caillebotte's Paris Street, A Rainy Day. There were more aristocratic visitors than previously, but several of these asked for a refund of the ticket price when they had seen the paintings. Still, some harsh words were written about the exhibition such as "children entertaining themselves with paper and paints do better" (Roe, 179). Overall, there were more favourable reviews this time, or at least less hostile ones, as the art establishment came to realise it could not go on ignoring the impressionists indefinitely. Renoir, in particular, was favoured with some positive reviews.

The Fourth Exhibition

Paul Gauguin (1848-1903) and Mary Cassatt (1844-1926) were invited to participate for the first time in this, the fourth exhibition. Over 260 works by 15 artists were on display. There were oil paintings, pastel works, and painted fans (thought to be more saleable). This time some coloured frames were used for certain works when it was considered complementary to the art. For example, Cassatt's Woman with a Fan was given a vermilion frame. The exhibition was the most successful so far in terms of visitors – some 16,000 – and money, with each artist receiving a dividend of 439 francs.

The Fifth Exhibition

Into a new decade and despite the slight progress being made, several impressionist stars decided to no longer participate in a fifth outing: Monet, Renoir, and Alfred Sisley (1839-1899). The remainder were also falling out over who to include as impressionism was a vague term encompassing many different styles. Held in a building under construction, the noise proved a disruption to the appreciation of the art. The 18 artists involved were, in truth, of mixed ability.

The Sixth Exhibition

This exhibition returned to the location of the first, but it was a very different set of artists on display compared to seven years earlier. There was still no Monet, Renoir, or Sisley, and no Caillebotte or Cézanne. Degas took advantage of these absences to dominate the show of 170 works and include his sculpture The Little Dancer, which caused a sensation. The ever-present Pissarro was the most represented artist, while Morisot and Cassatt received favourable reviews.

The Seventh Exhibition

There was a shakeup again of who could participate, and with some of the artists gone who were regarded as lesser talents, some big names returned, notably the trio of Monet, Renoir, and Sisley. However, Degas this time abstained. The exhibition was well promoted by Durand-Ruel who had booked the venue. The exhibition was better attended than any of its predecessors, but the reviews remained decidedly mixed – one critic commented that a Monet sunset looked like "a slice of tomato stuck onto the sky" (Roe, 239). There were even rumours spread that Monet and some of his peers were colourblind.

The Eighth Exhibition

For the 8th Impressionist Exhibition in 1886, Berthe Morisot and Eugène Manet financed the whole thing, which was held in a space above a famous restaurant, the Maison Dorée. There were 17 artists on show. Degas was back with lots of nude females bathing, but Monet, Sisley, and Caillebotte were now disillusioned with the whole affair and the constant bickering between artists. Art had moved on again by now, and there were some new styles like pointillism as seen in the works of Georges Seurat (1859-1891) and Paul Signac (1863-1935). The impressionists had become the neo-impressionists. The infighting and lack of coherence of the exhibition were noted by critics and Morisot described it as "a complete fiasco" (Howard, 105).

A New Approach

By the late 1880s, the impressionists were more or less in agreement that these general exhibitions of multiple artists were no longer the best way forward. Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890) and Gauguin, for example, organised an exhibition of their work and a few select others in a restaurant in 1887. There were also similar annual exhibitions to the impressionists in Paris such as those put on by the group of artists known as Le Vingt in Brussels from 1884. More significantly, the major dealers were now organising solo exhibitions for artists, including places like Brussels and New York where the reaction from the critics and public was more favourable.

Following Gustave Caillebotte's death in 1894, his impressive collection of impressionist art was donated to the state and shown in the Musée du Luxembourg. Times had certainly moved on, and the impressionists themselves had been replaced by younger artists; names like Henri Matisse (1869-1954) and Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) would become the champions of the avant-garde. The old impressionists had certainly revolutionised art, and their exhibitions had broken the mould of not only what was considered fine art but also where and how it should be admired. Things would never be the same again.