The Protestant Reformation (1517-1648) was one of the most significant cultural, political, and religious events in the history of Europe and helped shape the modern world. It was a complex event spanning over 100 years, which radically changed the way people understood themselves, religion, society, and ultimately how one defines truth.

Prior to the Reformation, the Catholic Church was the sole spiritual authority in medieval Europe (c. 476-1500). The medieval Church provided order and meaning to the lives of adherents from baptism as infants through weekly attendance at services, marriage rites, and the last rites at death. After one died, the Church taught, one's destination was determined by a loving God who was also just and punished those who died in their sins with an eternity of torment since they had rejected the gift of God's grace. There was no arguing with the tenets of the Church because there was no other spiritual authority one could turn to as an option.

The Protestant Reformation changed that dynamic completely when the German theologian and Catholic monk Martin Luther (l. 1483-1546) inadvertently challenged the authority of the Church by questioning the practice of selling indulgences (writs that promised to shorten one's stay – or that of a loved one – in purgatory). Luther's activism in Germany inspired others to make their own stand based on individual interpretation of the Bible and the concept that faith alone and scripture alone was all a believer needed to commune with God. The teachings of the Church were then understood by Protestants as human-made corruptions, which should be rejected by true believers.

Although there are many interesting facts concerning the Reformation, the following ten encapsulate key concepts of the movement overall. Modern-day scholars disagree on the precise dates of the Reformation, but it can safely be said that, within 100 years of Martin Luther's 95 Theses written in 1517, European society had been radically transformed and would continue to be influenced by the vision of the early reformers up through and into the modern era.

There Were Reformers before Martin Luther

Before Martin Luther's 95 Theses sparked the Reformation, other attempts had been made to correct what were seen as abuses and false teachings of the Catholic Church. The Paulicians and Waldensians had advocated reform while the Cathars separated themselves completely from the Church. The two best-known proto-Reformers, however, are the English theologian and priest John Wycliffe (l. 1330-1384) and the Bohemian priest Jan Hus (l. c. 1369-1415). Wycliffe inspired Hus, whose efforts were the driving force behind the Hussite Wars (1419 to c. 1434) and the Bohemian Reformation (c. 1380 to c. 1436), two of the earliest attempts at reform. Martin Luther would later reference Hus, who was executed in 1415 as a heretic, as a role model for Christians in pursuing a true relationship with God based solely on faith and one's own interpretation of scripture. Contrary to legend, however, Hus never 'predicted' Luther's activism; this story is a later invention by Luther's followers.

Martin Luther Did not Initially Want to Break with the Church

Luther had no intention of breaking with the Church and establishing a new vision of Christianity in 1517. He was a Catholic priest and theologian whose 95 Theses were written as an invitation to debate the subject of indulgences, which he claimed were unbiblical. The 95 Theses were published and translated by his followers, whose support encouraged Luther to make his stand against the Church. Just as Luther's 97 Theses a month earlier, initially, these were also only an invitation for scholarly debate. Once the Church reacted by trying to silence his objections to indulgences, Luther fought back by denouncing Church policy and practice, and so the Reformation began.

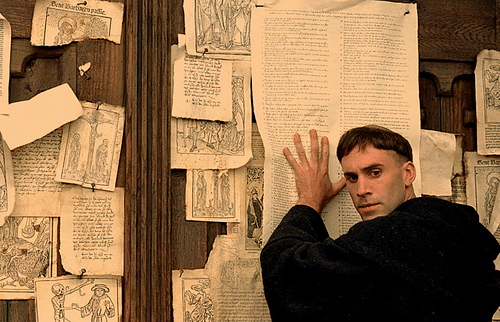

Luther May Never Have Nailed his 95 Theses to the Wittenberg Church Door

The iconic image of Luther nailing his 95 Theses to the door of the Wittenberg Church on 31 October 1517 is easily the most famous of the Protestant Reformation, but, according to modern scholarship, that event may never have happened. The story did not appear until years later when it was circulated by Luther's right-hand man Philip Melanchthon (l. 1497-1560), who was not even in Wittenberg at the time the event allegedly took place. Luther himself makes no mention of nailing the theses to the church door in 1517 or afterwards, only saying that he sent his theses to the Archbishop of Mainz. The story has been accepted as historical truth for so long now, however, that it is usually repeated uncritically.

The Reformation Was not a United Movement

Although the event is always referred to as the Protestant Reformation, it was actually a series of separate movements more accurately termed reformations. In Germany, where Martin Luther led the cause, there was also Martin Bucer (l. 1491-1551), who disagreed with aspects of his vision, and Andreas Karlstadt (l. 1486-1541), who had his own ideas concerning 'true Christianity' as did the German Reformer Thomas Müntzer (l. c. 1489-1525). In Switzerland, Huldrych Zwingli (l. 1484-1531) disagreed with Luther on the nature of the Eucharist, and John Calvin (l. 1509-1564) advanced his own agenda, which differed from Zwingli's. Further, these reformers inspired others who then started their own Reformed movements within the larger Reformation, as in the case of the Anabaptists who rejected the second-class citizenship of women and, in opposition to other Protestant sects, elevated women to positions of authority.

Many Women Participated in the Early Years of the Reformation

Although male reformers have been highlighted by historians for centuries, many women contributed significantly to the Reformation, especially in the early years, as they saw in the 'new teachings' hope for an equal voice in public affairs and greater autonomy. Among the best-known are Katharina von Bora (l. 1499-1552), wife of Martin Luther; Argula von Grumbach (l. 1490 to c. 1564), Katharina Zell (l. 1497-1562), Marguerite de Navarre (l. 1492-1549), Marie Dentière (l.c. 1495-1561), Jeanne d'Albret (Joan III of Navarre, l. 1528-1572), and Olympia Fulvia Morata (l. 1526-1555). These women, and many others, advanced the cause of the Reformation, but as the movement became mainstream and the beliefs codified, women's contributions were sidelined, and the equality they had hoped for never materialized.

The Reformation Succeeded because of the Printing Press

The Reformation succeeded, while earlier efforts at reform had failed, primarily because of the invention of the printing press c. 1440. Wycliffe and Hus made many of the same points later articulated by reformers but lacked the technology to share their views with a wider audience. Martin Luther's 95 Theses were popularized through print, as were his other writings which were then translated and printed elsewhere, inspiring a wider movement outside of Germany. Women like Argula von Grumbach or Marie Dentiere would have had no public voice if not for the printing press, and it was also used effectively by Jeanne d'Albret in advancing the Protestant message during the French Wars of Religion. Translations of the Bible, commentaries on scripture, and attacks on the Catholic Church – as well as by the Church on Protestant sects – were all made possible by mass-produced books and pamphlets. The popularity of these religious works in print contributed to a rise in literacy in Europe, which is an aspect of the Reformation often highlighted.

The Reformation Contributed to Some of the Most Devastating Wars in European History

The challenge to the Church, which was previously considered the sole spiritual authority in Europe, resulted in a number of conflicts, which escalated in scope, savagery, and casualties beginning with the Hussite Wars and continuing through the Knights' Revolt (1522-1523) and the German Peasants' War of 1524-1525. Although the German Peasants' War, like some of the later conflicts, was not caused solely by religious differences, the vision of the Reformation played a major role by encouraging the lowest class to believe in the hope of a new order in which they would have greater autonomy. The French Wars of Religion (1562-1598) were the direct result of religious disagreements, and religious differences also contributed to the Eighty Years' War (1568-1648) and the Thirty Years' War (1618-1648), which killed over eight million people.

The Counter-Reformation Inspired Art & Music

The Counter-Reformation (also known as the Catholic Reformation, 1545 to c. 1700) was the Catholic Church's response to the Protestant Reformation during which it instituted reforms while also making an effort to restore its former centrality. One aspect of these efforts was an emphasis on art, architecture, and music which would elevate the minds of adherents and contrast sharply with the stark churches of the Protestants who had rejected iconography, music (to greater or lesser degrees depending on the sect), or any artistic renderings of Jesus Christ or other biblical figures. In music, some of the central figures were the English composer Thomas Tallis (l. c. 1505-1585), his student William Byrd (l. c. 1540-1623), and the Italian composer Isabella Leonarda (l. 1620-1704). In art, the Counter-Reformation inspired the works of Caravaggio (l. 1571-1610), El Greco (l. 1541-1614), Gerard Seghers (l. 1591-1651), and Peter Paul Rubens (l. 1577-1640) among others. The architecture of Catholic churches emphasized the grandeur of God and the elevating message of forgiveness and redemption while also making clear the power and preeminence of the Church when compared with the more modest churches of Protestant sects.

The Reformation Encouraged Democratic Ideals

Although Luther himself would have rejected the modern-day concept of democracy, the movement he set in motion encouraged democratic ideals. Luther's own works contributed to the German Peasants' War in which the lowest class fought for equal rights and representation in government, and the reformers who followed Luther encouraged the same. The Swiss reformer Heinrich Bullinger (l. 1504-1575) advocated for a democratic leadership of the Reformed Church, and Scottish Reformer John Knox (l. c. 1514-1572) established the Presbyterian Church of Scotland as a democracy. Since Protestant reformers rejected the hierarchy of the Catholic Church, they gravitated toward a more egalitarian political and administrative structure, which was codified by John Calvin whose teachings informed the beliefs of the Puritans and Separatists, who eventually established the New England colonies in what would become the United States. The Founding Fathers, though not Puritans in any sense, would later base their form of government on the church government the colonists were most familiar with. The structure followed by the Quakers, who also influenced the development of modern democracy in the United States, came directly from the Protestant rejection of a hierarchy, which encouraged democratic idealism and government.

There is No Agreement on When the Reformation Ended

Although the dates of the Protestant Reformation are generally understood as 1517-1648, there is no universal scholarly consensus on this, and some scholars advocate for a different dating. There are some scholars who claim the event should be dated from the time of Jan Hus' activism to the pre-industrial era (1400-1750) or from Martin Luther's 95 Theses to the revocation of the Edict of Nantes (1517-1685) because the revocation encouraged the mass exodus of Protestants from France who then established themselves elsewhere as clearly defined sects. The most commonly agreed dates mark Luther's 95 Theses as the beginning and the Peace of Westphalia that ended the Thirty Years' War as the conclusion since that conflict was initially encouraged by religious differences, which the Peace of Westphalia of 1648 sought, in part, to address.

Conclusion

The Protestant Reformation broke the unity and authority of the Catholic Church, creating a plurality in Christianity that did not exist before. Although there had been so-called 'heresies' that challenged the authority of the Church earlier, these were crushed, and the Church's primacy was always maintained. Renaissance concepts of humanism, which elevated the status of the individual, as well as technology such as the printing press, coupled with the overt corruption of the medieval Church, combined to spark a movement that would transform European thought, culture, and what was understood as 'truth.' Scholar Ulinka Rublack comments:

Reformations confronted Europeans with the fact that Christianity contained radically different truth claims – among Protestants, among Protestants and Catholics, and among all these faiths and Eastern Orthodox Christians. This meant that the history of and arguments embedded in truth claims were constantly reconstructed and questioned. Eventually, this contributed to the emergence of intellectual positions which recognize religions as cultural systems of meaning and explore their ideas, tensions, and limitations. (3)

Around 1500, spiritual truth was understood as whatever the Church said it was; one hundred years later, 'truth' was much harder to define because, as the Church noted at the beginning of the Reformation, if anyone who could read the Bible could define 'truth,' then there was no longer an ultimate 'truth' to be defined. This aspect of the Reformation was probably the most profound in that it highlighted the power of the individual to determine one's own truth, whether in religion or any other area of life, and it marked the transition from medieval paradigms of thought to those of the modern era.