Jeanne de Jussie's Short Chronicle (1535) is an eyewitness account by the nun Jeanne de Jussie (l. 1503-1561) relating how the Protestant Reformation in Geneva, Switzerland, impacted the lives of the sisters of her convent of Poor Clares. The work is significant in providing a counterpoint to the Protestant versions of the event.

The writings of Protestant reformers like John Calvin (l. 1509-1564), Marie Dentière (l. c. 1495-1561), and Heinrich Bullinger (l. 1504-1575), among others, present the Reformation in Geneva as a triumph of truth over error, during which a majority of the citizens gratefully responded to the 'new teachings' and rejected the precepts of the Catholic Church. Jeanne de Jussie's account contradicts this in relating how the reformers and their followers persecuted the sisters of the convent, insisting they were either being held against their will or were servants of Satan, obstinately refusing to accept the Reformed version of Christianity to continue in the 'perversion' of Catholicism.

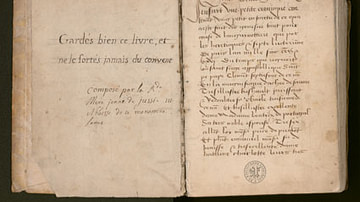

The work was never written for publication but only as a record of the events experienced by the sisters to be kept in the convent and read aloud to preserve the memory of what had happened. It was published in 1611 by a Catholic press under the title The Leaven of Calvinism or The Beginning of the Heresy of Geneva in order to encourage military action by Catholics against Protestants. The Short Chronicle continued to be published periodically afterwards, always edited to greater or lesser degrees, until a complete version was made available by the scholar Helmut Feld in 1996. Today it is usually included in any study of the Protestant Reformation or the Catholic Counter-Reformation for its insight into what it was like to be a devout Catholic, especially a devout Catholic woman, during the early Reformation era.

Jeanne de Jussie & the Reformation

Jeanne de Jussie entered the convent of Poor Clares at the age of 18 in 1521, just as Martin Luther's 95 Theses were gaining a wide audience. Martin Luther (l. 1483-1546) had initiated the Reformation in Germany in 1517, and by 1519, the Swiss Reformer Huldrych Zwingli (l. 1484-1531) was preaching the reformed vision in Zürich. The nuns of the Poor Clares may not have known of these developments because their vows, which included chastity, obedience, and poverty, also stipulated enclosure in the convent and a severing of ties with the outside world.

The nuns of the Poor Clares devoted themselves to prayer and fasting for the sins of the world and did not engage with the people of the city. All needs were met by the sisters themselves, who had specific tasks such as vicar, doorkeeper, gardener, cook, bursar, and nurse. Jeanne de Jussie served as the convent's secretary. She seems to have lived among her fellow sisters peacefully until the Reformation began making headway in Geneva in the 1530s.

Although many women of the time chose the monastic life for themselves, others had had it chosen for them, and the Reformation provided a way for these reluctant nuns to free themselves from what they had come to consider a prison. The most famous example of this is Martin Luther's wife, Katharina von Bora (l. 1499-1552), a former nun, though there were many others, including Marie Dentière. This does not seem to have been the case at the convent of the Poor Clares of Geneva, however, nor was it generally the case elsewhere.

To the reformers of Geneva, however, who preached against monastic orders, no one would willingly remain in a convent, bound by vows forced upon them, unless they were either held against their will or in the service of the forces of darkness and working to ensnare 'true Christians' in the 'lies' of the Catholic Church. They sent emissaries to the convent in an attempt to draw the nuns out or be allowed to preach the 'new teachings' of reform to them in their own sacred space. Reformers Guillaume Farel (William Farel, l. 1489-1565) and Pierre Viret (l. 1511-1571) tried to convert the sisters without success, and Marie Dentière then visited the convent and, according to de Jussie, was shunned.

In the following excerpt from de Jussie's work, the Syndics (highest elected officials in Geneva) arrive at the convent expressly to demand the sisters attend a debate the following Sunday between their Father Confessor and the reformers. The Reformed belief was that if a person who sincerely had a 'heart for Christ' heard the gospel message preached truly (as defined by the reformers), they would reject the artifice of Catholicism for the genuine vision of Christianity. It was inconceivable to the reformers that the sisters of the Poor Clares were living lives they had freely chosen, which they only wanted to continue to live in peace.

The Text

The following text is taken from A Reformation Reader: Primary Texts with Introductions edited by Denis R. Janz, pp. 402-405, drawing on the translation of A. C. Lane from The Rise of Calvinism or the Beginning of Heresy in Geneva by Jeanne de Jussie, edited by A. C. Grivel, crosschecked with The Short Chronicle: A Poor Clare's Account of the Reformation of Geneva by Jeanne de Jussie, translated by Carrie F. Klaus. Paragraphs have been broken at points for clarity. The scene takes place between the sisters inside the convent and the Syndics standing outside the barred entrance, possibly speaking through a small window in the door.

As, then, the stated deadline approached, the Syndics in person ordered the Father Confessor of the Sisters of Sainte Claire to appear without fail at the Convent of St. Francis for the debate.

Then on the Friday of the Octave of Corpus Christi at five in the afternoon, when the sisters were gathered in the refectory to have their light meal, the Syndics came to the door along with several other great heretics, telling the mother doorkeeper that they were coming to announce to the Ladies that they had to be present at the debate the following Sunday. The mother doorkeeper sent this pitiful news to the sisters at once and asked that the mother abbess and her vicar should come speak to the men and give an answer. They went there together. Those women who remained in the refectory to keep community were soaked in the abundance of the wine of anguish and sang Compline in tears lamentably. The mother abbess and vicar greeted the Syndics humbly, and these men told them that all the nuns were bound by the command of the Messieurs to appear without fail at the debate. The women answered humbly, "Sirs, you have to excuse us, for we cannot obey this order. All our lives we have been obedient to your lordships and to your commands in what was legitimate for us. But this order we must not obey, for we have taken a vow of holy perpetual enclosure, and we wish to observe it."

The Syndics answered: "We have nothing to do with your ceremonies; you must obey the commands of the Messieurs. In any case, solid citizens have been called together for this debate in order to become acquainted with and to demonstrate the truth of the Gospel, because we must come to a unity of faith."

"How is that?" said the mother abbess and the vicar. "It is not the profession of women to take part in debates, for such things are not prescribed for women. You don't think that they should take part in debate, seeing that it is even forbidden to uneducated men to get at all involved in explaining Holy Scripture. A woman has never been called to debate, nor to give testimony, and in this we do not wish to be the first. It would not do you honor to want to force us to be there."

So the Syndics answered them: "All these reasons are useless to us: you will come there with your father confessors, whether you wish to or not." The mother vicar told them, "Sirs, we beg you in the name of God, turn away from the desire to force us to do such a thing and don't prevent us in any way from going to the service of worship. We certainly don’t believe that you are the Syndics, given your simple questions. For we believe the Syndics to be so wise and considered that they would not deign to think of wishing to give us any trouble or displeasure. But these are wicked boys who have no other pastime than to molest the servants of God."

The Syndics said to the lady vicar, "Don't try to trifle with us! Open your doors! We will come in, and then you will see who we are and what authority we have. You have in there five or six young ladies who have lived in the city, and when they see us, they will tell you just who we are, for we are solid citizens, Governors and Councilors of the city."

"In good time," said the mother vicar. "But for right now you can't come in here, nor can you speak to the ones you want, for they are worshipping at Compline, and we wish to go there too. Bidding you a good evening."

The Syndics answered the lady vicar: "They are not all of your mind, for there are some of them that you are holding by force in there, by your traditions and bribes, and who would soon turn to the truth of the Gospel, if it were preached to them. And in order that no one should claim ignorance, the Messieurs have ordered this debate in the presence of everyone and wish that all of you should come there together."

"Sirs," said the sisters. "Save your grace, for we have all come inspired by the Holy Spirit and not by constraint in order to do penance and to pray for the world, and not for the sake of laziness. We are not at all hypocrites, as you say, but pure virgins."

So one of the Syndics answered, "You have really fallen from truth, for God has not at all commanded so many rules, which human beings have contrived; and in order to deceive the world and under the title of religion they are servants of the great Devil. You want us to believe that you are chaste, a thing which is not possible by nature; but you are totally corrupt women."

"What," said the mother vicar. "You who call yourselves Evangelists, do you find in the Gospel that you ought to speak ill of someone else? The devil can well take away from what is good, but he has no part in us." The Syndic said, "You name the devil, and you make yourselves seem so holy." "It is following your example," she said, "for you name him at your pleasure and I do it as a reproach." The Syndic said, "Madam Vicar, be quiet and let the others speak who are not at all of your opinion." The mother vicar said, "I am willing. My sisters," she said, "tell the Messieurs our intention."

And then the three doorkeepers, the bursar, and two cooks, the nurse and several of the old mothers who were there to hear the conclusion all cried out together in full voice, "We speak as she does and wish to live and die in our holy vocation." And then the men were all astonished to hear such cries, telling each other, "Listen, Sirs, what a terrible racket these women inside are making, and what an outcry there is."

The mother vicar answered, "Sirs, this is nothing. You will hear much more if you take us to your Synagogue, for when we will all be together, we will make such a noise that we will remain unvanquished."

"Now," said the Syndics, "you are in high dudgeon, but you will come there."

The mother vicar answered, "We will not."

"We will take you there ourselves," they said, "and so you will never go back to your own land, for each of us will take one of you to his house and we will take her every day to the preaching services, for she must change her wicked life and live according to God. We have lived wickedly in the past. I have been," said the Syndic, "a thief, a bandit, and a Sybarite, not knowing the truth of the Gospel until now."

The mother vicar answered: "All those works are wicked and against the divine commandment. You do well to amend your life, for you have lived badly. But neither my companions nor I, thanks be to the Lord, have ever committed a murder or any such works so as to need to take up a new life, and so we don't wish to change at all, but to continue in the service of God." And she spoke to them so forcefully, along with the mother abbess and the doorkeeper, that they were all amazed.

"Lady Vicar," said the Syndic, "you are very arrogant, but if you make us angry, we will make you sorry."

"Sirs," she said. "You can do nothing but punish my body, which is what I most desire for the love of my God. For on behalf of the holy faith, neither my company nor I wish at all to be dissemblers; our Lord wants us to confess him before human beings, and if I say something which displeases you, I want to accept the punishment for it all by myself. So that you may know better who I am, and that others may not have unhappiness on my account, my name is sister Pernette of Montleul or of Chasteau-fort."

When these evil men saw that they were wasting their time, they left, ending the conversation by saying furiously all together, "We enjoin you all a second time, on behalf of the Messieurs, not to fail to be present with your father confessors next Sunday, early, at the Convent of St. Francis at the debate we have mentioned, and we do not intend that someone will have to come to get you." And so they left.

When they had gone away, the reverend mother abbess, the vicar, and the doorkeepers went up to the church with the others and then lifted the cloth from the grille to adore the Holy Sacrament which was lying on the altar, as is a very praiseworthy custom. Then, lying prostrate on the ground, all together in a loud voice representing themselves as poor sinners and asking God for mercy – it was enough to break a pious heart – seeking from this good Jesus and the blessed Holy Spirit grace to be able to escape these dangers and perils.

Conclusion

As it happened, the sisters were unable to remain at the convent after the Calvinists gained the upper hand in the various debates, and they left for the city of Annecy in Southern France in 1535. As the Protestant Reformation spread, the Catholic Church responded with the movement now known as the Catholic Counter-Reformation, and Annecy became an important center for this movement in advancing Catholic thought and denouncing the Protestants as heretics. Jeanne de Jussie is thought to have begun her work shortly after arriving in Annecy in 1535, most likely completing it in 1547. Her stated goal is to preserve the events that brought them from Geneva to Annecy, as scholar Carrie F. Klaus notes:

Jussie states several times that her main goal in writing the chronicle is historical: she does not want these important events to be forgotten. "I promise that I write nothing I do not know to be true," she says at one point, adding, "and still I do not write a tenth of it, but only a very small part of the main events so that they will be remembered, so that in the future those who suffer for the love of God in this world will know that our ancestors suffered as much as we do, and as people after us will, and always, to varying degrees, in the example of Our Lord and Redeemer who suffered the first and the most." Jussie almost certainly did not intend to publish her text, but rather expected for it to remain as a record for her present and future sisters in the Convent of Saint Clare. (24)

At some point, it was removed from the convent (or a copy was) and made its way to the Catholic press of the Four Brothers of Chambery who published it in 1611 in the hopes that de Jussie's first-hand account would inspire the Catholic Duke of Savoy to attack Protestant Geneva, which it failed to do. The 1611 publication did acquire a wide readership, however, and the work continued to be published, in varying forms, throughout the 17th century and into the 19th and 20th.

Presently, the Short Chronicle of Jeanne de Jussie is recognized as one of the most important accounts of the early years of the Protestant Reformation and, according to some scholars, a proto-feminist work illustrating how women were able to direct their own lives through the monastic orders. The reformers, from Luther to Calvin and beyond, noted how former nuns had left their convents once they heard the 'true' gospel of Jesus Christ, but the Short Chronicle presents the other side of the story, making clear that the Reformation's message was not always welcome and not always as well-received as Protestant writers of the time so often claimed.