The French exploration of New Zealand has been overshadowed by the achievements of British navigator Captain James Cook (1728-1779), but French navigators who visited Aotearoa's (New Zealand) shores named over 100 geographical places and significantly contributed to European knowledge about New Zealand. The honour of sailing the first French vessel into New Zealand waters in 1769 goes to Jean-François Marie de Surville (1717-1770).

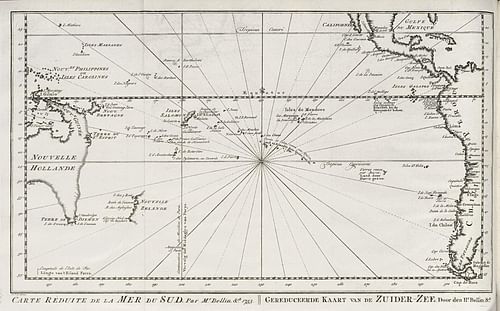

Jean-François Marie de Surville commanded the St. Jean Baptiste, a 32-gun, 650-ton ship on a commercial venture from French India. After entering the Pacific and leaving the Solomon Islands, an outbreak of scurvy forced de Surville to attempt to make for land in the southeast. The French knew of the existence of New Zealand, thanks to the maps of Dutch explorer Abel Janszoon Tasman (1603-1659), who had charted the west coast from Hokitika in the South Island to Cape Maria van Diemen in the north of the North Island more than 120 years earlier.

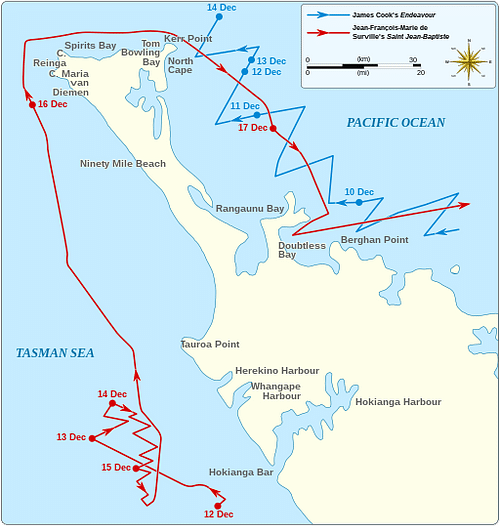

The New Zealand coast south of Hokianga (North Island) was sighted on 12 December 1769, but de Surville found no safe harbour to anchor, so he continued north in stormy seas. The St. Jean Baptiste sailed off Ninety Mile Beach on the west coast of the far north of the North Island before being driven by a westerly gale towards Murimotu Island (off North Cape). As the French vessel rounded North Cape, the British navigator Captain James Cook (1728-1779) was sailing up the east coastline from the south on the Endeavour. Wind gusts blew the Endeavour northeast and farther out to sea, and although the two ships were out of visual range of one another, their paths crossed, and on 16 December 1769, the two navigators passed within 50 kilometres (31 mi) of each other off the coast of the North Island.

De Surville's Secret Mission

Unlike Cook, who was on a scientific voyage to record the transit of Venus, Jean-François Marie de Surville was appointed commander of St Jean Baptiste and set off from Pondicherry, India, on 2 June 1769 on what at first glance appeared to be a trading expedition backed by a syndicate that arose after the financial collapse of the Compagnie des Indes (French India Company) in 1769.

The ship's cargo of Portuguese wine, fine lace, opium, and bolts of silk – worth more than £150,000 in 18th-century currency – was not the usual trading trinkets. The French interest in the southern seas was fuelled by rumours of the fabled Ile Davis (Davis Island or Davis Land), an island said to have been discovered in 1687 near Rapa Nui (Easter Island) by the English buccaneer Edward Davis (fl. c. 1680-1688), skipper of the Bachelor’s Delight. The Abbe Alexis Rochon (1741-1817) – a French astronomer and traveller of the south seas – was a witness to the excitement surrounding the possibility of a mysterious land of gold and silver:

I was in Pondicherry in August 1769 when the rumour spread that an English vessel had found in the South Sea a very rich island where, among other peculiarities, a colony of Jews had been settled. The account of this discovery . . . became so well known that it was believed in India that the purpose of de Surville's voyage . . . was to search for this marvellous island.

(Quoted in Lee, 41).

The cargo carried by St. Jean Baptiste was to be sold for gold and silver, and a French trading post was to be established on Davis Island.

De Surville, who was born on 18 January 1717 in Port-Louis, Brittany, went to sea at the age of ten with the French India Company and served in the French navy during the Seven Years' War (1756–1763). Despite this experience, de Surville relied on older navigation techniques such as dead reckoning to find longitude. The St. Jean Baptiste soon found itself becalmed after entering the Pacific by way of the Strait of Malacca and the Philippines and made slow progress to the Solomons, making landfall on Choiseul Island on 7 October 1769. The Solomon Islands had been 'lost' since being discovered by Álvaro de Mendaña de Neira (1542-1595). Mendana failed to confirm his discovery for Spain and so de Surville is considered to have 'rediscovered' the island group, but due to the inaccuracy of his maritime charts, de Surville thought the Solomons were an extension of New Guinea.

By this stage of the St. Jean Baptiste's voyage, the 200-strong crew, who had been expecting a trading voyage to China, were stricken with scurvy, and tension had broken out with the indigenous population. A landing party, led by de Surville's second-in-command, was ambushed as they searched for fresh food and water, with one crew and several islanders killed. St. Jean Baptiste had been leaking on the high seas, and fearing further local reprisals, de Surville left the Solomons and headed south to seek supplies in New Zealand before continuing to Davis Island. Having now lost 34 crew to scurvy, de Surville used Tasman's reports and charts and sailed by reckoning down the 35th parallel, sighting the New Zealand coast just south of Hokianga on 12 December 1769.

At the same time, the Endeavour was charting the east coast of the North Island using a method called a running survey, which was achieved from the deck of a moving ship. Compass bearings of landmarks were taken from different vantage points, and compass variations were found by noting the sun's altitude (which established latitude) and consulting lunar tables to find longitude by measuring the angular distances of stars from the moon. During his exploration, the Endeavour passed a bay on the Karikari Peninsula in the Far North (North Island), and Cook named it Doubtless Bay.

Unaware that Cook had sailed this way or that their paths had crossed, de Surville reached Doubtless Bay on 17 December and called it La Baie de Lauriston (Lauriston Bay) in honour of the governor of Pondicherry and one of his financiers, Law de Lauriston (1719-1797). He also named Surville Cliffs on the northernmost tip of the North Island, a name which is still used. The St. Jean Baptiste anchored on the western side of Doubtless Bay and spent 14 days there as the crew collected plants to restore health. Paul-Antoine Leonard de Villefeix (1728-1780), a French Dominican priest and chaplain on board the St. Jean Baptiste, most likely gave the first Catholic mass in New Zealand as de Surville and his crew spent Christmas Day in the bay.

De Surville and his men made detailed observations of flora and fauna, noting, for example, that the pulp of karaka fruit is edible and a rich source of vitamin C. The first written description of the pōhutukawa tree (New Zealand's Christmas tree) was in French when Jean Pottier de l'Horme (born c. 1738), a lieutenant aboard the St. Jean Baptiste with a keen interest in plant life, noted its bright red blooms. Local Maori showed the French how to find fresh greens and locate streams to refill their water casks. De Surville asked for permission to cut down trees to repair the ship and presented the iwi (nation or tribe) with rice, peas, and two pigs.

The French set sail on 31 December 1769, due to worsening weather but also because relations with the Maori had deteriorated. A small boat was alleged to have been stolen, and de Surville retaliated by burning some fishing canoes and huts and seizing a rangatira (chief). Ranginui was a rangatira from the local iwi, Ngāti Kahu, and de Surville, who was impressed by the Maori, hoped to learn more about their language and culture.

De Surville headed for South America, taking up the search for Davis Island again. Instead of sailing to California and then down to South America, de Surville attempted a trans-Pacific crossing, a gruelling voyage that took more than three months. Scurvy, which had once again broken out amongst the crew, took Ranginui's life in March 1770 as the St. Jean Baptiste was in sight of the Juan Fernandez Islands, and de Surville perished two weeks later. Desperate to get help from the Spanish, the French captain anchored off the seaside town of Chilca, donned full dress uniform, and headed ashore in a skiff. The rough surf claimed the skiff and de Surville.

Du Fresne's Voyage

The second notable French visit to New Zealand shores was by Marc-Joseph Marion du Fresne (1724-1772), a privateer who had served in the French navy and the French India Company. Du Fresne's mission was to return to his homeland a Tahitian taken to Paris by Louis-Antoine, Comte de Bougainville (1729-1811) in 1768. Ahutoru (c. 1740-1771) had volunteered to serve as an apprentice sailor under the French navigator aboard the frigate Boudeuse. Unfortunately, Ahutoru contracted smallpox when one of du Fresne's ships, the 22-gun Mascarin, took on supplies in Madagascar, and he died three weeks later.

Since it was no longer necessary to sail to Tahiti, the Mascarin headed to Cape Town to rendezvous with the 16-gun Marquis de Castries and take on further victuals. In October 1771 and with eighteen months' provisions, du Fresne (who financed the voyage by mortgaging his property and depleting his life savings) decided to search for Gonneville Land – the French term for the unknown southern continent – named after the French explorer, Binot Paulmier de Gonneville, who, during a violent storm at the Cape of Good Hope in 1504, made for the first land he could sight, believing it to be Terra Australis. Gonneville received a hospitable welcome and stayed ashore for six months on what is now believed to be part of the coast of Brazil around Santa Catarina Island.

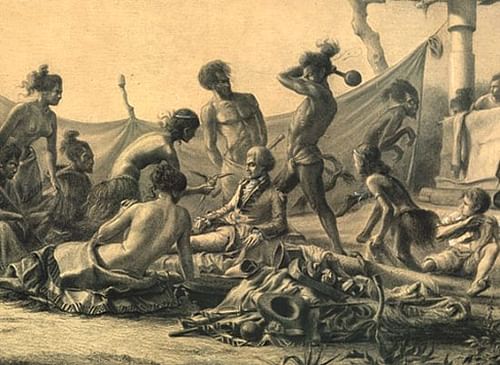

Du Fresne's discoveries in the south Indian Ocean included Marion Island, Prince Edward Island, and the Crozets (named after his second-in-command Julien-Marie Crozet (1728-1782). On 3 March 1772, he sighted Van Diemen's Land (Tasmania), following Abel Tasman's route, and he and his crew were the first Frenchmen to make contact with Tasmanian Aboriginals after making landfall in Blackman's Bay.

The Tasmanians, who had initially welcomed the French, soon made hostile gestures as three small boats from the two vessels attempted to land ashore. Muskets were fired, spears were thrown, and on 10 March 1772, the Mascarin and the Marquis de Castries sailed from Blackman's Bay, heading for New Zealand. Du Fresne sighted Mt. Taranaki (North Island), naming it Pic Mascarin, unaware that it had already been named Mt. Egmont by Captain James Cook in January 1770. In search of fresh water and timber for ship repairs, du Fresne sailed north and reached the Bay of Islands (northeastern coast of North Island), anchoring his ships off Moturua Island for a five-week stay.

Unlike du Surville, who was sensitive to local iwi customs, du Fresne’s crew violated tapu (sacredness or taboo) by cutting down trees, including kauri, for masts and fishing in waters where fishbones had been scraped but not yet laid to rest. The French also inadvertently became involved in inter-iwi rivalry, and the local iwi, Ngāti Pou, feared the French would establish a permanent settlement.

The simmering tension led to du Fresne's death on 12 June 1772. The commander went ashore with some crew members, and when they had not returned by nightfall, officers thought du Fresne had decided to spend the night with the local iwi, but they later learnt that the men had been attacked and killed. This was puzzling since, on 8 June, du Fresne had been welcomed at a special pōwhiri (ceremony) by the rangatira of the Te Hikutu hapū (clan or subtribe). It is possible his attendance at the pōwhiri bestowed favouritism on the Te Hikutu hapū in the eyes of rival iwi, or perhaps there was an ongoing yet unintentional violation of tapu by the crew. Either way, it is not known why du Fresne was attacked, but 25 crew lost their lives.

Du Fresne's expedition was now in the hands of 20-year-old Ambroise Bernard Marie Le Jar du Clesmeur (1751-1805), who commanded the Marquis de Castries, and Julien-Marie Crozet, who initiated fierce reprisals that led to the deaths of around 250 Maori, the burning of a pā (fortification) and destruction of waka (canoes). The French were in no position to depart immediately as ship repairs were not complete, but the two ships set sail for home via Manila on 12 July 1772, after the officers buried a bottle on Moturoa Island, claiming New Zealand for Louis XV of France (r. 1715-1774) and calling it France Australe. Du Fresne's untimely death strengthened the French view that no attempt should be made to settle New Zealand, and it was 20 years before another French expedition visited. Maps of the northeastern coastline and a sketch of a pā were, however, valuable contributions to European knowledge of Aotearoa.

In Search of La Pérouse

In March 1788, French naval officer and explorer, Jean-Francois de Galaup, Comte de la Pérouse (b.1741), left the fledging British penal colony of Botany Bay in Sydney, Australia, and was never heard from again. La Pérouse, who was inspired by Captain Cook's Pacific voyages of discovery, was sent by Louis XVI of France (r. 1774-1792), to gather information about the penal settlement.

Antoine Bruny d'Entrecasteaux (1737-1793) commanded an expedition to the Pacific in 1791 in search of La Pérouse, calling into Ambon in the Moluccas, Admiralty Islands, the Solomons, Tasmania, and he explored the western and southern Australian coastline before taking a route from Maria Island (Tasmania) to New Zealand. It was known that La Pérouse had not visited New Zealand. So, d'Entrecasteaux and his ships, Recherche and Esperance, sighted Three Kings Islands (islands northwest of Cape Reinga, the northern tip of the North Island) and did some brisk trading with iwi of cloth and axes for fresh fish before heading north, where d'Entrecasteaux discovered and named the Kermadec volcanic island group in 1793. He failed to find any trace of La Pérouse's ships, L'Astrolabe and La Boussole, but his surveyor charted the coastline from Cape Maria van Diemen to the Surville Cliffs.

Scientific Expeditions

The still-raw memory of du Fresne's death and the intervening Battle of Waterloo (1815) meant that the next significant visit by the French to New Zealand did not occur until April 1824, when Louis-Isidore Duperrey (1786-1865) sailed into the Bay of Islands on La Coquille, a horse barge converted to a corvette. The French remained uninterested in settlement; Duperrey's expedition was to gather botanical and ethnographic knowledge. He arrived at the height of the Musket Wars (inter-iwi conflict from 1807-1837) and stayed for two weeks before continuing a circumnavigation of the world.

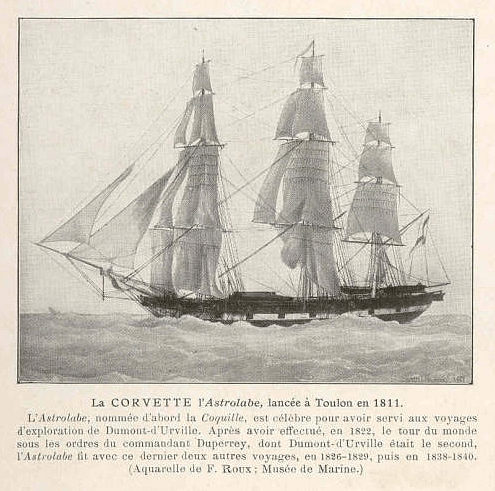

Duperrey's second-in-command was Jules Sébastien César Dumont d'Urville (1790-1842), a botanist and cartographer who returned to New Zealand on the Astrolabe voyages (1826-1829 and 1837-1840). La Coquille was renamed the L'Astrolabe in honour of La Pérouse, and d'Urville's mission was to complete Captain Cook's charts by conducting a hydrographic survey, continue the search for La Pérouse, and collect botanical specimens.

D'Urville's list of achievements is considerable. During the Astrolabe voyages, he collected over 1,600 plant specimens, including manuka, koromiko, toetoe, and rimu; produced the first major charts of New Zealand since those of Cook and corrected a mistake in them; navigated the first ship through the treacherous and narrow French Pass (from Tasman Bay through into Admiralty Bay in the Marlborough Sounds); lent his name to Durvillaea and Grateloupia urvilleana (seaweeds), the shrub Hebe urvilleana, and the buttercup Ranunclus urvilleanus; and named an unknown penguin species after his wife (the Adélie penguin). His multivolume work, Voyage au Pôle Sud et dans l'Océanie, proved d'Urville to be an astute anthropologist as it contained detailed observations of Maori culture.

His most intriguing legacy is an unpublished novel he wrote on a homeward voyage – Les Zélandais, Histoire Australienne. Set in 1819-1821, it tells the story of the effects of European contact on Maori. Tragically, on 8 May 1842, d'Urville, aged 52, his wife, and son Jules, who were on their way from Versailles to Paris, were killed in a train derailment.

French Place Names in Aotearoa

In August 1840, 60 French settlers from Rochefort arrived in Akaroa (Banks Peninsula, South Island) and established a settlement. The French navy built a church, hospital, roads and bridges, but all were unaware that New Zealand was now in the hands of the British Crown, following the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi on 6 February 1840. Akaroa is a popular tourist destination with a distinctly French flair, and many descendants of the settlers still live in the region.

The French influence on New Zealand has been preserved through geographical names, such as Petit Carenage Bay, Duvauchelle, Le Bons Bay, Mount Bonpland, Mount Napoleon, La Pérouse Glacier, Mascarin Glacier, Aiguilles Rouges, and Eiffelton.