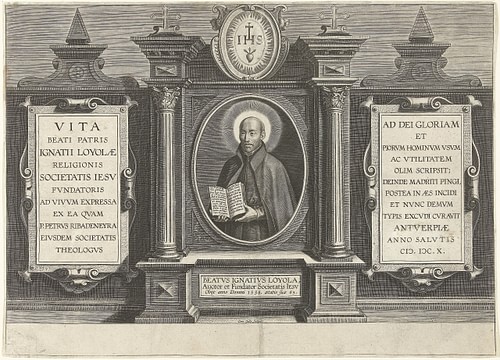

The Autobiography of Saint Ignatius is the story of the life of Ignatius of Loyola (l. 1491-1556) dictated by him to the Jesuit priest Father Louis Gonzalez between 1553-1555, shortly before Loyola's death in 1556. It is an account of his conversion, spiritual struggles, and the establishment of the Society of Jesus, better known as the Jesuits.

According to Father Gonzalez, Loyola had resisted telling his story in the past, but in poor health in 1553 and encouraged by others of his order, he consented to have Gonzalez take dictation while he narrated his life from his youth onward. Loyola's many responsibilities as head of the Jesuit order prevented an unbroken time in which this could be done, and so Gonzalez met with him when time allowed, writing down what he said so precisely that, as he later noted, he sometimes had no idea what Loyola had meant by a given line but faithfully included all that was narrated.

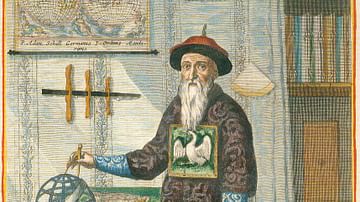

The autobiography was published in 1555 for members of the order and served as the inspiration for the 1609 Illustrated Biography of Ignatius of Loyola issued in honor of his beatification by Pope Paul V. The 1609 work tells Loyola's story entirely through images without text, but it is informed by his autobiography which begins in 1521 at the Battle of Pamplona and concludes with the pope approving the Jesuit Order in 1540.

Loyola & Luther

Loyola's response to what he understood as the call of God to service is sometimes compared with that of Martin Luther (l. 1483-1546) whose objection to the sale of indulgences began the Protestant Reformation (1517-1648). As scholar Diarmaid MacCulloch (among others) has noted, Luther's spiritual revelation inspired his challenge to the authority of the Catholic Church while Loyola interpreted his experience as encouraging obedience, devotion, and service to the same.

Martin Luther was a devout Catholic theologian and monk until he was led to question the Church's teachings after a spiritual crisis c. 1513. He could not reconcile the precepts of the Church with what he felt about the nature of God until he had a spiritual revelation that convinced him that God justified believers through faith alone, not works, and that the Church's teachings were wrong in this as well as on many other important issues. If one were justified by faith alone and could receive God's messages through scripture alone, Luther concluded, there was no need for the intercession of the Church and its various rules and regulations.

Loyola, who had never given religion much thought until after he was wounded in battle in 1521, recognized the vital importance of faith but came to believe that the spirit of God and the spirit of the Church were the same and so faithful service to the Church was service to God. This being so, he concluded, questioning the Church amounted to challenging the divine will. The conversion experience would eventually lead to Loyola's Spiritual Exercises (1548) in which he makes his stand clear on questioning the Church's authority in his famous line, "What seems to me white, I will believe black if the hierarchical church so defines" (Point 13, Janz, 429).

The Text

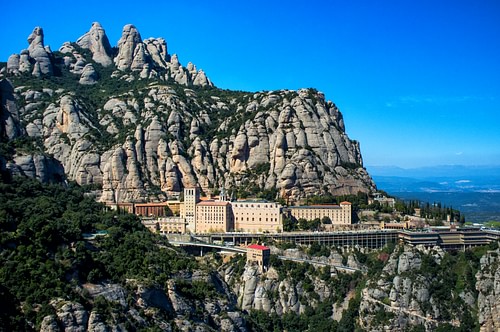

The following excerpt is taken from The Autobiography of St. Ignatius as dictated to Father Louis Gonzalez, edited by J. F. X. O'Connor, S. J., 1900. It narrates Loyola's life from his wounding at the Battle of Pamplona through his conversion experience and his vigil before the altar of the Virgin Mary at Montserrat, where he renounced his former life and dedicated himself to the service of Christ and the Church (chapter 1 and part of 2, pp. 20-37). Throughout the autobiography, Loyola refers to himself in the third person.

Up to his twenty-sixth year, the heart of Ignatius was enthralled by the vanities of the world. His special delight was in the military life, and he seemed led by a strong and empty desire of gaining for himself a great name. The citadel of Pamplona was held in siege by the French. All the other soldiers were unanimous in wishing to surrender on condition of freedom to leave, since it was impossible to hold out any longer; but Ignatius so persuaded the commander that, against the views of all the other nobles, he decided to hold the citadel against the enemy.

When the day of assault came, Ignatius made his confession to one of the nobles, his companion in arms. The soldier also made his to Ignatius. After the walls were destroyed, Ignatius stood fighting bravely until a cannonball of the enemy broke one of his legs and seriously injured the other.

When he fell, the citadel surrendered. When the French took possession of the town, they showed great admiration for Ignatius. After twelve or fifteen days at Pamplona, where he received the best care from the physicians of the French army, he was borne on a litter to Loyola. His recovery was very slow, and doctors and surgeons were summoned from all parts for a consultation. They decided that the leg should be broken again, that the bones, which had knit badly, might be properly reset; for they had not been properly set in the beginning, or else had been so jostled on the journey that a cure was impossible. He submitted to have his flesh cut again. During the operation, as in all he suffered before and after, he uttered no word and gave no sign of suffering save that of tightly clenching his fists.

In the meantime, his strength was failing. He could take no food and showed other symptoms of approaching death. On the Feast of St. John, the doctors gave up hope of his recovery and he was advised to make his confession. Having received the sacraments on the eve of the feasts of Saints Peter and Paul, toward evening, the doctors said that if by the middle of the night there were no change for the better, he would surely die. He had great devotion to St. Peter and so it happened by the goodness of God that, in the middle of the night, he began to grow better.

His recovery was so rapid that in a few days he was out of danger. As the bones of his leg settled and pressed upon each other, one bone protruded below the knee. The result was that one leg was shorter than the other and the bone, causing a lump there, made the leg seem quite deformed. As he could not bear this, since he intended to live a life at court, he asked the doctors whether the bone could be cut away. They replied that it could, but it would cause him more suffering than all that had preceded, as everything was healed, and they would need space in order to cut it. He determined, however, to undergo this torture.

His elder brother looked on with astonishment and admiration. He said he could never have had the fortitude to suffer the pain which the sick man bore with his usual patience. When the flesh and the bone that protruded were cut away, means were taken to prevent the leg from becoming shorter than the other. For this purpose, in spite of sharp and constant pain, the leg was kept stretched for many days. Finally, the Lord gave him health. He came out of the danger safe and strong with the exception that he could not easily stand on his leg but was forced to lie in bed.

As Ignatius had a love for fiction, when he found himself out of danger, he asked for some romances to pass away the time. In that house there was no book of the kind. They gave him, instead, "The Life of Christ", by Rudolph, the Carthusian, and another book called "Flowers of the Saints", both in Spanish. By frequent reading of these books, he began to get some love for spiritual things. This reading led his mind to meditate on holy things, yet sometimes it wandered to thoughts which he had been accustomed to dwell upon before.

Among these, there was one thought which, above the others, so filled his heart that he became, as it were, immersed and absorbed in it. Unconsciously, it engaged his attention for three and four hours at a time. He pictured to himself what he should do in honor of an illustrious lady, how he should journey to the city where she was, in what words he would address her, and what bright and pleasant sayings he would make use of, what manner of warlike exploits he should perform to please her. He was so carried away by this thought that he did not even perceive how far beyond his power it was to do what he proposed, for she was a lady exceedingly illustrious and of the highest nobility.

In the meantime, the divine mercy was at work substituting for these thoughts others suggested by his recent readings. While perusing the life of Our Lord and the saints, he began to reflect, saying to himself: "What if I should do what St. Francis did?" "What if I should act like St. Dominic?" He pondered over these things in his mind and kept continually proposing to himself serious and difficult things. He seemed to feel a certain readiness for doing them, with no other reason except this thought: "St. Dominic did this; I, too, will do it." "St. Francis did this; therefore, I will do it." These heroic resolutions remained for a time and then other vain and worldly thoughts followed. This succession of thoughts occupied him for a long while, those about God alternating with those about the world. But in these thoughts there was a difference. When he thought of worldly things it gave him great pleasure, but afterward he found himself dry and sad. But when he thought of journeying to Jerusalem, and of living only on herbs, and practicing austerities, he found pleasure not only while thinking of them, but also when he had ceased.

The difference he did not notice or value until one day the eyes of his soul were opened and he began to inquire the reason of the difference. He learned by experience that one train of thought left him sad, the other joyful. This was his first reasoning on spiritual matters. Afterward, when he began the Spiritual Exercises, he was enlightened and understood what he afterward taught [others] about the discernment of spirits. When gradually he recognized the different spirits by which he was moved, one, the spirit of God, the other, the devil, and when he had gained no little spiritual light from the reading of pious books, he began to think more seriously of his past life, and how much penance he should do to expiate his past sins.

Amid these thoughts, the holy wish to imitate saintly men came to his mind; his resolve was not more definite than to promise, with the help of divine grace, that what they had done, he also would do. After his recovery, his one wish was to make a pilgrimage to Jerusalem. He fasted frequently and scourged himself to satisfy the desire of penance that ruled in a soul filled with the spirit of God.

The vain thoughts were gradually lessened by means of these desires – desires that were not a little strengthened by the following vision. While watching one night, he plainly saw the image of the Blessed Mother of God with the Infant Jesus, at the sight of which, for a considerable time, he received abundant consolation, and felt such contrition for his past life that he thought of nothing else. From that time until August, 1555, when this was written, he never felt the least motion of concupiscence. This privilege we may suppose from this fact to have been a divine gift, although we dare not state it, nor say anything except confirm what has already said. His brother and all in the house recognized from what appeared externally how great a change had taken place in his soul.

He continued his reading meanwhile and kept the holy resolution he had made. At home, his conversation was wholly devoted to divine things, and helped much to the spiritual advancement of others.

Ignatius, starting from his father's house, set out upon his journey on horseback…Arriving at a village situated a short distance from Montserrat, he determined to procure a garment to wear on his journey to Jerusalem. He therefore bought a piece of sackcloth, poorly woven, and filled with prickly wooden fibers. Of this he made a garment that reached to his feet…

Thus equipped, he continued on his way to Montserrat, pondering in his mind, as was his wont, on the great things he would do for the love of God. And as he had formerly read the stories of Amadeus of Gaul and other such writers, who told how the Christian knights of the past were accustomed to spend the entire night, preceding the day on which they were to receive knighthood, on guard before an altar of the Blessed Virgin, he was filled with these chivalric fancies, and resolved to prepare himself for a noble knighthood by passing a night in vigil before an altar of Our Lady at Montserrat. He would observe all the formalities of this ceremony, neither sitting nor lying down, but alternately standing and kneeling, and there he would lay aside his worldly dignities to assume the arms of Christ.

Conclusion

Loyola's vigil and commitment at Montserrat would lead him to eventually establish the Society of Jesus (Jesuits), approved by the pope in 1540, which would become the most influential and widespread Catholic order in the world. The Jesuits were central to the efforts of the Catholic Counter-Reformation which condemned the claims of the Protestant Reformation as heresy and sought to reestablish the authority of the Catholic Church. Religious differences between Catholics and Protestants informed or led directly to the most devasting military conflicts in Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries, but two of the central figures on either side, initially, were simply trying to understand God's role in their lives and then, by extension, in others'.

At the heart of both Luther's and Loyola's convictions was a spiritual awakening, and yet each interpreted the message from God in different ways, which then dictated not only the path of their own lives but of many others up to the present day. MacCulloch comments:

The transformation was symbolized by the night's vigil Loyola spent before the pilgrimage statue of the Black Madonna at Montserrat on her feast of the Annunciation (25 March 1522); it was meant to be the eve of his proposed (though in fact subsequently much-delayed) departure for Jerusalem, and he was dedicating himself as a knight on the eve of his knighting, while throwing off the outward splendors of a Castilian courtier. Luther's parallel solitary struggles with God led him ultimately to a sense that his salvation was an unconditional gift of God, making him free of all his natural bonds; this freedom empowered him to defy what he saw as worldly powers of bondage in the medieval Western Church. Ignatius found that his encounter with God was best expressed in forms drawn from the Iberian society which had created the most triumphant form of that same Church: chivalric expressions of duty and service. The contrasting conversion experiences thus led respectively to rebellion and to obedience. It was a momentous symbol of what came to separate Protestant Reformation and Catholic Counter-Reformation. (221)

These movements, informed to greater or lesser degrees by both men, would change the world. The Protestant Reformation defied the authority of the status quo, while the Counter-Reformation maintained that tradition could be adhered to and yet remain relevant in changing times. According to various scholarly views, these two Reformation movements are ongoing in the present day and, in large part, are informed by the very different responses of Martin Luther and Ignatius of Loyola to what they understood as messages from the same God.