The Dreyfus Affair, or L'Affaire as it has become known, demonstrated the competing forces at work to either reestablish the monarchy and the Church in power or to solidify and advance the unfulfilled ideals of the 1789 French Revolution. This event is considered the trigger for the movement which led to the Law of Separation of Churches and the State in 1905.

The affair shook France to its core and led to the widespread reexamination of its republican values. It may be difficult to properly appreciate the importance of L'Affaire more than one hundred years after its occurrence. Yet modern historians continue to showcase this as a major contribution to the necessity of the establishment of a secular Republic in which liberty, equality, and fraternity might prevail for all citizens regardless of creed or without creed, where both belief and unbelief would be protected. L'Affaire "made possible a coalition of all defenders of the Republic on the basis of anticlericalism. . . . Even after Dreyfus was vindicated, the Affair continued to divide the nation" (McManners, 1972: 119).

Clericalism & Anticlericalism

The Dreyfus Affair is connected to the intensified clerical and anticlerical struggle waged between Catholic and Republican forces following the crushing French defeat in 1870 at the hands of the Prussians. The military loss was a blow to national pride, carried with it the annexation of Alsace-Moselle, and contributed to the low morale of the French military. On one hand, those on the anticlerical, political left ascribed the defeat to the continued influence of the Church in institutions of higher learning. On the other hand, those who supported the Church and the monarchy saw the defeat as a sign of judgment on a nation that had turned from God and the divine right of kings. These two opposing forces would struggle for dominance, and Captain Dreyfus (1859-1935) would become an unwitting pawn to galvanize both sides in the contest for the French form of government. Dreyfus' arrest, trial, exile, exoneration, and reinstatement would widen the gap between the political left and right.

Captain Dreyfus was a Jew from Alsace-Lorraine, a long-disputed region which had returned to Prussian control after 1870. He became a convenient scapegoat to assign blame for France's inglorious defeat and revealed the divide between supporters of the Church and supporters of a laïque (secular) Republic. The incident began with a secret memorandum (bordereau) which was discovered in a wastebasket by a cleaning woman and addressed to the German military attaché in the German Embassy in Paris. The bordereau, written in French, contained information on various aspects of the French army – French artillery, troop placements, and a discussion on obtaining information about a field artillery operating manual. Captain Dreyfus was assigned to an artillery unit, and suspicion fell upon him as the author of the bordereau in part because he was Jewish. He was arrested and accused of treason. The case early on received little interest but was inflamed by elements of the antisemitic press, including the Catholic publication La Croix "which called for the expulsion of Jews from France" (Begley, 2009: 75).

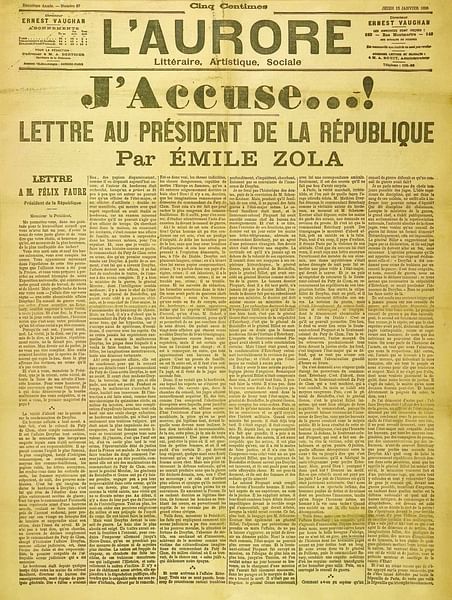

Zola & J'Accuse

The details of the Dreyfus Affair mesmerized not only the French public but reverberated internationally. French novelist and playwright Émile Zola (1840-1902) issued his famous J’Accuse (I accuse) in 1898, an elegant and scathing open letter written to the French president Félix Faure. The letter was published in the newspaper L'Aurore in defense of Dreyfus. Zola "denounced the framing of Dreyfus by the military hierarchy and constructed the affair as a struggle between liberty and despotism, light and darkness" (Gildea, 105). He addressed the president respectfully and with gratitude to inform him of what Zola considered would be a blemish on the president's name – "this abominable Dreyfus affair" (cette abominable affaire Dreyfus).

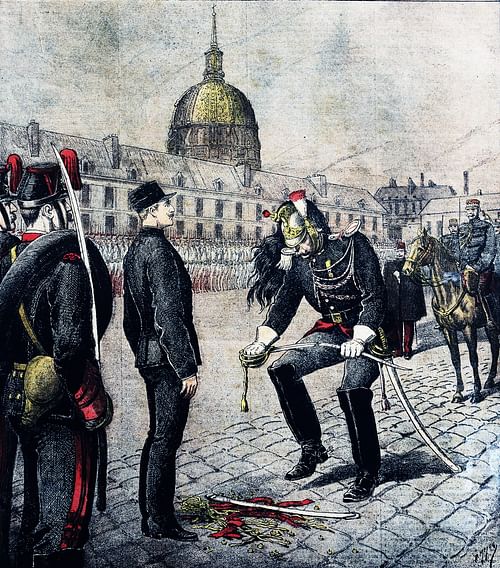

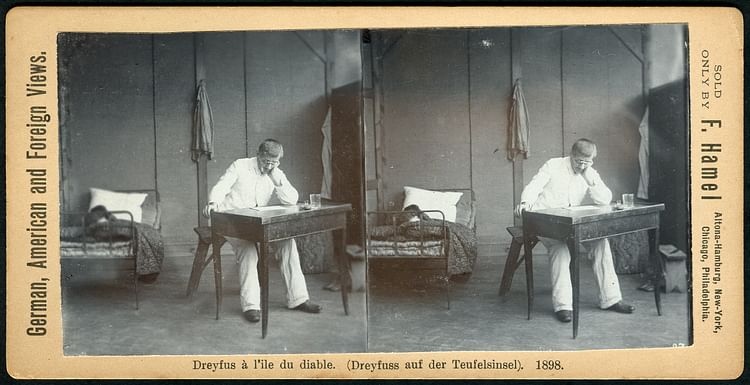

Zola informed the president about the process and condemnation of Dreyfus. He spoke of "the nothingness of the accusation" (le néant de l’accusation) and described the plot with all the elements of a mystery novel needed to captivate the public – complicity at the highest military levels, conspirators in the shadows, forged documents, anonymous letters, mysterious women, fabricated evidence, and secret meetings. He warned the French of dictatorship. He recounted that Captain Dreyfus was condemned for treason, court-martialed, publicly shamed, stripped of his rank in the courtyard of the École Militaire, and exiled to Devil's Island with Church and military complicity. He revealed that only when Colonel Sandherr died and was replaced by Colonel Picquart (1854-1914) as head of intelligence did the truth come out about Commander Esterhazy being the real traitor. Even then, the military refused to reopen the investigation for fear that the condemnation of Esterhazy would lead to a review of Dreyfus' judicial process. Picquart was sent out of the country on missions to Tunisia and other places to silence his insistent voice and plea to clear Dreyfus. The general staff could not confess its crime since it would sully the military's reputation, a military still reeling from the defeat in the Franco-Prussian War. Losing face and public scorn was to be avoided at all costs.

The condemnation, degradation, and exile of Dreyfus would set in motion his defense by the Republicans. Zola named names beginning with the Lieutenant Colonel du Paty de Clam, the judicial officer of the affair, who was identified as noxious, the one most culpable in the affair, and who threatened Dreyfus' wife to remain silent. Zola reproached other military officers, such as Sandherr, Mercier, Boisdeffre, and Gonse, for committing judicial errors, for being accomplices in what he considered one of the century's most evil plots, for withholding proof of Dreyfus' innocence, and for committing the crime out of Catholic fervor and biased investigation. He accused three graphologists of fraud in their analysis of documents, charged the war ministry with using the press to influence public opinion, and condemned the first court-martial for introducing secret documents leading to the guilty one's acquittal. He admitted that he did not personally know those he accused and did not speak out of hatred. The enormous influence of Zola would contribute to Dreyfus' eventual exoneration and later provide support for the rationale and the defense of the law separating the Catholic Church from the State.

Several references figure prominently in J'Accuse which demonstrate the suspected underlying religious influences in how L'Affaire was conducted. According to Zola, General Boisdeffre (1838-1906), head of general staff, seemed to yield to his clerical views. Lieutenant Colonel du Paty de Clam (1853-1916) was accused of being involved with spiritism and occultism and speaking with spirit beings. The generals Gonse and Mercier were also suspected of yielding to their religious passions. Du Paty de Clam was further accused of being part of a clerical milieu, hunting for "dirty Jews" (sales juifs) who dishonored the times in which they lived. Zola described L'Affaire as a crime that hid behind antisemitism and exploited patriotism. The scandal was viewed as a threat to society and the survival of the Republic in which Zola feared human rights (droits de l'homme) would die (Zola, 1898).

For his efforts, Zola would be condemned for defamation and experience self-exile in England for a year. However, there was no turning back as the Antidreyfusards and the Dreyfusards staked out their positions. The Antidreyfusards had the support of the Church and the army and were persuaded of the existence of a syndicate grouping anti-France, Jewish, Protestant, and Freemasonry forces. The Dreyfusards had the support of writers, artists, and scientists. The radicals and free thinkers denounced the alliance of the Church and the army. There were more insistent calls for the expulsion of all Jews from France. L'Affaire and its eventual resolution, including a second trial in 1899, left France shaken. In the minds of many, "since it was anticlericals, not churchmen, who rescued an innocent man from Devil's Island, the inference was drawn that the Catholics, in the last resort, put expediency before truth and order above justice" (McManners, 120). This overlooked the fact that some churchmen, though relatively few in number, supported Dreyfus and that Colonel Picquart was Catholic. However, it fed the narrative that would continue to pit anticlerical forces against their clerical opponents.

Catholic Church Complicity

Pope Leo XIII (1810-1903) had previously "urged French Catholics to support the Republic, but the effects of the Dreyfus case largely undid his efforts" (Walker et al, 672). This policy of rallying Catholics to the Republic may have appeared for a moment to give a chance for a moderate Republic, but in 1898, following the Dreyfus Affair, many Republicans reinforced their anticlerical commitment.

Like another piece of make-believe, but grimmer, the incredibly long-drawn-out Dreyfus Affair aroused passion and prejudice throughout the world. In France, the chain of misdeeds –treason, coercion, perjury, forgery, suicide, and manifest injustice – re-created the cleavage of the ‘two Frances,’ always reoccurring at critical moments. (Barzun, 630)

Elected Prime Minister in 1899, Waldeck-Rousseau (1846-1904) "made a political decision against the Church because he had seen how the clergy played politics against the Republic" (McManners, 127). At his first trial in 1894, Dreyfus' conviction had been pronounced unanimously. Since then, evidence for Dreyfus' innocence had become overwhelming. Dreyfus was convicted a second time in 1899 but without unanimity among the judges and with extenuating circumstances. He was pardoned after the second court-martial with the consent of President Émile Loubet (1838–1929). The government justified its decision to pardon Dreyfus based on his deteriorating health after five years of exile and imprisonment on Devil's Island. Both Waldeck-Rousseau and Loubet were considered traitors and enemies of the Church. Dreyfus' supporters would continue their struggle for his full rehabilitation which the pardon did not provide and he was finally reinstated into the army in 1906 (1932: 39–40).

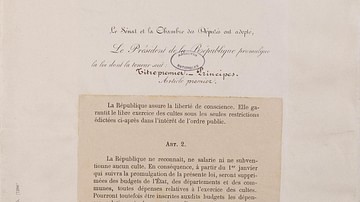

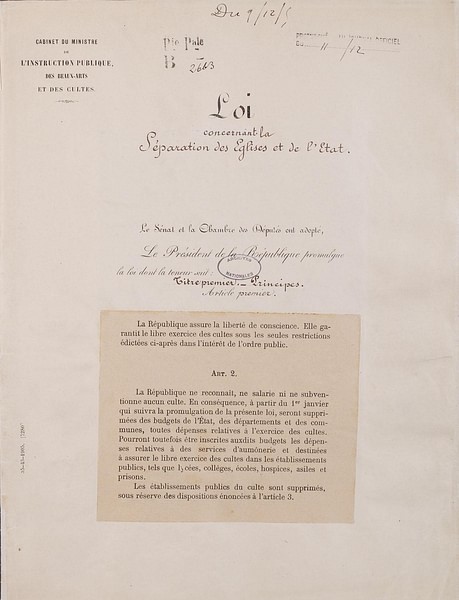

A first step against the Church was taken in 1901 with the Law of Associations which required governmental authorization for religious teaching orders (congrégations). The refusal of authorization would lead to closure and confiscation of property and forced many religious workers into exile. It was only a matter of time before the Church came under more intense pressure. Émile Combes, who followed Waldeck-Rousseau, applied the law with a vengeance. Parliament rejected most of the requests by religious congregations for authorization, and diplomatic relations with the Vatican suffered. In 1899, René Waldeck-Rousseau, in the wake of political chaos brought about by the Dreyfus Affair, was called upon to lead the government as Council President. Finally, in 1905, "a radical republican legislature mindful of diatribes in La Croix and kindred publications (collectively christened 'la bonne Presse') voted the separation of Church and State" (Brown, 218).

Conclusion

Centuries of religious struggles have unsurprisingly produced much cynicism and distrust toward religion in France. The Dreyfus Affair during the Third Republic epitomized the conflict between clerical/monarchist and anticlerical/republican forces. The Law of Separation in 1905 abrogated the 1801 Napoleonic Concordat, which had favored Catholicism, Lutheranism, Reformed Protestantism, and later Judaism. The status gained by the recognized religious confessions under the Concordat was not granted to other confessions, which were repressed for being unrecognized confessions. Historian Carluer asserts that the liberty granted by Napoleon was not liberal; it was a means to govern. The first article of the Concordat prohibited ministry in France to all foreigners, which severely hindered evangelical expansion in the country. The Napoleonic penal code harshly sanctioned all possibility of gatherings apart from official religious confessions.

France experienced a long and delicate transition toward religious liberty. This exhausting struggle explains the weak development of evangelicalism in France. However, evangelicals gained a newfound status due to the support of many evangelical leaders for Captain Dreyfus during L'Affaire. Evangelical churches experienced momentum with evangelistic campaigns widely held. The Baptists and independents (libristes) were the most active in politics with several influential senators leading up to 1905. There was an emphasis on morality and economic justice and an unprecedented increase of Protestant evangelization in France with the Catholic Church viewed as hostile to the Republic. "On their little scale, Evangelical Protestants fully profited from the deficit of elites at the summit of the Republic due to the temporary quarrel with the Catholic Church" (Fath, 128-29). The Dreyfus Affair remains one of the most significant events in French history which led to the separation of church and state and contributed to the principle of freedom of religion and liberty of conscience in France.