The apparatus of colonial government in the Spanish Empire consisted of multiple levels, starting with the monarchy and Council of the Indies at the top and moving down to the viceroy, audiencias, mayors, and local councils. The system was designed to extract wealth from the colonies and to spread the Christian faith, but these two aims were often in conflict, as were the various branches of colonial government throughout the imperial period.

The Pyramid of Government

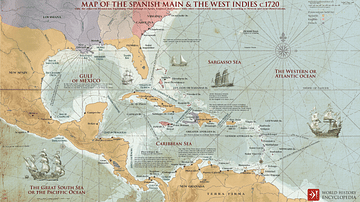

Spain colonised vast parts of the Americas starting from the landing by Christopher Columbus (1451-1506) in 1492. Working through the Caribbean islands and then moving on to the mainland in the first decades of the 16th century, by 1570, some 100,000 Europeans were governing over 10 million indigenous peoples who inhabited lands from what is today the southern United States to the southern tip of Argentina. Included, too, were the Philippines. The tentacles of power of the Spanish monarchs were many and long as they attempted to keep control of people, officials, and resources from afar. The various levels of government in the colonies of the Spanish Empire included:

- Royal decrees from the Spanish monarchy

- Directives from the Council of the Indies

- Decisions made by the viceroy

- Legislation passed by the audiencia

- The regulations controlled by the corregidor

- The collection of taxes and revenues by the Official Real

- The decisions of the alcaldes mayores (mayor) and town council

Council of the Indies

The Council of the Indies (El Real y Supremo Consejo de las Indias) was based in Spain, and it was created by Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (r. 1519-1556) in 1524 to oversee all colonial matters in the Americas and the Spanish East Indies. The name of this institution comes from the term then used to describe the Americas, the 'Spanish Indies'. The only authority above the council was the monarchy itself. Its members were few, between six and ten, all appointed by the monarch. Operating until 1834, it tried to balance the twin aims of colonization: wealth acquisition and the conversion of new peoples to Christianity. One of the major directives of the Council of the Indies was that local peoples should be protected or, at least, not over-exploited to the point of starvation and death.

In the late 15th and early 16th century, the Spanish Crown had first used a sort of franchise system of awarding individuals the right to conquer new territories and extract wealth. The office of adelantado was awarded to conquistadors ("conquerors"), like Christopher Columbus, Franciso Pizarro (1478-1541), and Ferdinand Magellan (c. 1480-1521), who agreed to fund expeditions to subdue local peoples and establish colonies. The reward was the right to govern and keep 80% of the wealth they came across; the Crown received the other 20%. The adelantado also agreed to ship a certain number of settlers and clergymen to the colony. A year or so later, the state then stepped in and appointed officials of its own to govern the new colony and establish a more formal system of government with its head, the viceroy, and various other officials reporting directly to the Council of the Indies.

The Council of the Indies drew up legislation for the colonies, scrutinised and approved the expenditures of colonial officials, gave permission to conduct wars and generally supervised military matters, inspected expedition ships, collected import and export duties, interviewed potential expedition leaders and heard their reports in person on their return, set down the geographical scope of expeditions, and heard appeal cases from the colonial audiencias (see below). The Council made colonial and ecclesiastical appointments and could impose fines, confiscations of property, and prison sentences on those who did not follow regulations.

Incorporated into the Council of the Indies was the Casa de Contratación de las Indias, which was responsible for all matters of trade in the colonies, acting as the sole clearing house and supervising the treasure fleets that sailed back and forth across the Atlantic. The Casa de Contratación appointed an official for every ship bound for the Americas who had the responsibility to inspect crews, cargoes, and passengers and to record everything that went on aboard and at port. Another duty of the Casa de Contratación was to organise all the invaluable knowledge that colonial administrators sent back to Spain, such as maps, notes on local resources, and descriptions of local peoples. Finally, the Casa acted as an advisory board to the Council of the Indies regarding civil and ecclesiastical colonial appointments. The Council of the Indies was all-powerful until the 18th century when some of its responsibilities began to be redistributed to other ministries such as the Ministry of the Navy and the Indies.

Viceroys

The viceroy directly represented the Spanish Crown in their particular colonial territory, a viceroyalty being the largest administrative area within the empire. There were eventually four viceroyalties:

- The Viceroyalty of New Spain (today's Mexico, Central America, parts of the southern United States, the Caribbean Antilles, and the Philippines). Established in 1535.

- The Viceroyalty of Peru (from Panama to Tierra del Fuego). Established in 1542 and first known as New Castille.

- The Viceroyalty of New Granada (northern South America). Established in 1717 when it split from the Viceroyalty of Peru.

- The Viceroyalty of Rio de la Plata (Paraguay, northern Argentina, and eastern Bolivia). Established in 1776 when it split from the Viceroyalty of Peru.

Viceroys, who were usually noblemen, were chosen by the monarch in consultation with the Council of the Indies. Their term of office ranged from three to five years, and they resided in the capital of their viceroyalty (Mexico City, Lima, Sante Fe de Bogotá or Buenos Aires). The viceroy had overall responsibility for the colony; he headed the bureaucracy bristling with colonial secretaries (escribanos de gobernación), commanded the army, and supervised the collection of royal revenues. The viceroy also headed the activities of the Church under the system of Patronato Real whereby the popes in Rome had, in 1501 and 1508, given the Spanish monarchy absolute powers over church matters in the colonies. The bishops of the Spanish Catholic Church were not entirely happy with this arrangement, and there was much jostling for supremacy between church and crown officials throughout the colonial period.

The viceroy's practical powers were limited by several other institutions and appointed officials, and, in charge of such a vast geographical area with many distinct population groups, he was dependent on a huge apparatus of administration that was poorly interconnected due to inadequate road systems. Another curb on a viceroy's powers was the semi-autonomy of subordinates like the captain-generals who governed in more remote and less populated areas of the viceroyalty. As a consequence of these difficulties, the two new viceroyalties of New Granada and Rio de la Plata were formed in the 18th century by splitting off territory from the viceroyalty of Peru. Another consequence was that most viceroys simply perpetuated the status quo, ensuring that existing forms of government, laws, and conventions continued as they had under their predecessors. Indeed, viceroys could not usually pass local legislation as this was the responsibility of the individual audiencias (see below). However, a viceroy could be the president of the audiencia in his city of official residence.

Corregidores

The corregidor was a judicial and political officer who directly represented the Spanish Crown. He was, in effect, the governor of a specific area. The corregidor in New Spain served for five years if selected from Spain, but only three years if recruited locally. In Peru, he served for just one year. The corregidor appointed administrators (tenientes) for each of the cities in his jurisdiction or corregimiento. He was responsible for regulating the prices of foodstuffs and maintaining public buildings, urban streets, squares, and sanitation in his district. As the salary was relatively low for those in smaller towns, a corregidor often made himself rich by acting as a middleman between European merchants and the indigenous population both in terms of goods and forced labour, a situation ripe for corruption.

Audiencias

All the major cities of the Spanish Empire had an audiencia, which was responsible for certain legal, political and commercial matters which concerned both European settlers and indigenous peoples. The audiencia had jurisdiction over a particular city and its surrounding area. It met in regular sessions (acuerdos) and passed legislation (autos acordados) relevant to local affairs. Audiencias also acted as an important advisory body for the viceroy.

An audiencia was composed of a president and a panel of judges or oidores (from 3 to 15 depending on a city's importance). Judges were appointed for life but had restrictions on their commercial activities and public life to ensure they could not be easily corrupted. The audiencia is thus the prime example of Spain's general approach to colonial governance: local affairs were to be put in the hands of legally trained individuals and great faith was put in legal codes. The president of the audiencia had no voting rights, and at least in theory, he was forbidden from influencing the audiencia's judges and officers in legal matters. The lower part of the audiencia was staffed by a large number of attorneys (fiscales), notaries, reporters, and minor officials such as clerks of the court (escribanos de cámara).

The audiencia was responsible for hearing the appeals against decisions made by the city's lower courts. The rulings of the audiencia regarding criminal matters could not be overturned, but in civil cases, a final appeal could be made to the Council of the Indies. Cases involved European settlers' relations with each other, relations between European and indigenous peoples, and relations between indigenous peoples themselves.

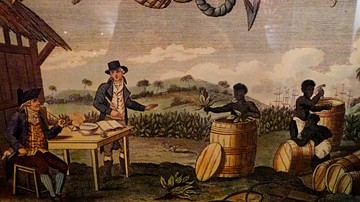

The audiencia granted settlers the right to use forced labour (repartimiento in New Spain and mita in the Viceroy of Peru). Under this system, local communities were obliged to provide regular quotas of men to work on colonial projects like the construction of roads and public buildings. Other duties of the audiencia included assessing the size and type of tributes indigenous communities were required to pay the Spanish Crown.

Alcaldes Mayores & Town Councils

Local town councils (cabildos) were led by a mayor (alcaldes mayores) who typically served for three years. Beneath the mayor were the councillors (regidores), between four and six in a small town and at least eight in larger towns. The councillors were initially appointed by the Crown but then elected by the local citizens (vecinos), that is property owners. Then there were the magistrates and minor administrators known as alcaldes ordinarios, the town clerk (escribano de cabildo), and officials such as the local chief constable (alguacil mayor) and the receptor de penas who collected fines imposed by the courts.

The cabildo governed not only a specific town but also the surrounding rural areas and smaller communities. The council could give out land grants and licenses to erect buildings, raised a militia force when necessary, raised local taxes, controlled the prices of certain goods, and was responsible for maintaining roads and the town prison. Alongside the main cabildo, there was a second council which governed indigenous peoples in the area and which had similar positions and responsibilities as its European twin but without certain judicial functions.

Interrelations & Limitations

All of the above institutions and individuals were so organised that they kept each other in check and resulted in no single person or body ever becoming so powerful that they might threaten the interests of the Spanish monarchy. Another specific policy to ensure this objective was to limit the terms of office of officials in any single location. The Crown was always very keen to avoid an official becoming too entrenched and, therefore, too powerful in one particular place. It was very difficult for even a viceroy to establish any lasting colonial roots (radicados), and such officials as the corregidor could not govern the area in which he normally lived. A consequence of this policy was that sometimes officials had little empathy for long-standing local issues, a situation which occasionally led to revolts against the centralisation of government.

The viceroys, captain generals, and audiencias all represented the interests of the Spanish Crown in the colonies. On the other side, the mayors and local councils represented the interests of the local community. Thus another balance of power was created. Dividing responsibilities ran right through the colonial infrastructure. For example, the four Official Real in each colony were responsible for collecting taxes and revenues, and all four were required to sign every single invoice.

In order to improve efficiency, the convention of residencia established a control on all senior colonial officials. At the end of an official's term of office, a lengthy inquiry was conducted to determine how they had conducted themselves. For a corregidor, the residencia lasted 30 days. At a public hearing, claimants could come forward against the conduct of the official, and, if found guilty of misgovernment, the official, although rarely directly punished, would be unlikely to receive a new position or promotion.

Within the institutions themselves, there was another interface of rivalries, this time between Spanish-born Europeans (peninsulares) and colonial-born Spaniards (criollos). An additional check on the institutions of government was a less tangible one but, nevertheless, an important one. This was the attitude of the Catholic Church, represented by certain ecclesiastical bodies and local leaders. A priest could denounce a corrupt official in a sermon in church and so do his reputation serious damage in the community. Church leaders were particularly keen to speak out against the overexploitation of indigenous peoples as this impeded one of the main aims of colonization: to convert locals to Christianity.

The efficiency of colonial government very often depended on the calibre and integrity of the individuals in office at any one time and place. Relative to the period, the highly centralised Spanish colonial government was a sophisticated apparatus which achieved its purpose, even if local interests might be trodden on and the decision-making process unbearably slow. Corruption was certainly a problem, although perhaps less prevalent in the higher steps of the pyramid of power. However, even the higher echelons suffered when the Crown decided to raise cash revenues by selling the offices of audiencia judge or local councillor, for example. Further, some offices became hereditary, and so people could hold positions without possessing the necessary skills. There was also much incompetence and neglect, particularly by those peninsulares officials only present in a colony for the short-term and out to further their careers back in Spain. Indeed, the mutual hatred of condescending outsider officials was one of the single most important factors in unifying the grass-root dissent that eventually led to revolution and freedom for the new independent states in the Americas.