The assassination attempt on Gaspard II de Coligny, Admiral of France (l. 1519-1572) on 22 August 1572 was the spark igniting the St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre beginning on 24 August and continuing in Paris for the next five days and elsewhere in France for over two months. Admiral Coligny was the first of the Protestants (Huguenots) slaughtered in Paris.

Admiral Coligny was a leading Protestant, who, even so, was an influential counselor to the Catholic King Charles IX of France (r. 1560-1574), son of Catherine de' Medici (l. 1519-1589). The first three of the French Wars of Religion (1562-1598) were concluded in 1570, and Catherine de' Medici had proposed an arranged marriage to the Protestant Queen of Navarre, Jeanne d'Albret (l. 1528-1589) between d'Albret's Protestant son, Henry of Navarre (later King Henry IV of France, l. 1553-1610) and her daughter Margaret of Valois (l. 1553-1615) in an effort to heal the religious divisions of the country, which had widened since 1562. The wedding date was set for 18 August 1572 and drew large numbers of Protestants to the Catholic city of Paris.

Among these were the most influential Protestant leaders, including Coligny, who were all housed in a certain area. After an unknown assassin made an attempt on his life, Coligny and the other leaders demanded action be taken, and the city council, king, and Queen Mother, fearing a Protestant uprising, responded by approving a plan to execute the leaders, beginning with Coligny. The massacre began early on 24 August after the city gates had been shut and locked and chains strung across the streets to hamper any attempts at escape or large-scale movements. Once the leaders had been killed, the common people followed the example of their leaders and massacred any Protestants or Protestant sympathizers they could find. Further slaughter of Protestants by Catholics followed in other cities, resulting in a death toll estimated at between 5,000 in Paris and over 25,000 total.

There are several eyewitness accounts and secondhand reports detailing the massacre, and among the best-known are Margaret of Valois' Account of St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre and Jacques Auguste de Thou's Death of Admiral Coligny. Others include the account of the Protestant Charlotte Arbaleste Duplessis-Mornay (l. 1550-1606) and Maximilien de Bethune, Duke of Sully (l. 1560-1641). All the firsthand accounts are consistent in their description of the chaos, terror, and violence of the massacre as are the secondhand reports, such as the one included in the Fugger Newsletter, 30 August 1572, on the assassination of Coligny.

Background on the Texts

The accounts left by Duplessis-Mornay and the Duke of Sully both detail their respective escapes from Paris while Margaret of Valois' is the only report written by a member of the royal family and describes events in the palace during the massacre. The account of Jacques Auguste de Thou (l. 1553-1617), who was in Paris with Henry of Navarre at the time, focuses on the death of Admiral Coligny, as does the anonymous report of 30 August 1572 published in the Fugger Newsletter.

The Fugger Newsletters were a collection of handwritten accounts collected in manuscript form by the brothers Philipp Eduard Fugger (l. 1546-1618) and Octavian Secundus (l. 1549-1600), which included news reports from around Europe, the Americas, Asia, and North Africa. Some of these reports carried the byline of the author while others were anonymous pieces. These reports were accounts of events considered newsworthy including royal weddings, politics, wars and rebellions, religious dissensions, and assassinations of public figures as well as other news.

De Thou was a widely-traveled and well-read scholar, who served as Counselor of State under Henry III of France (r. 1574-1589, brother of Charles IX) and Henry IV (r. 1589-1610). At the time of the St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre, he was in Paris as a young Protestant courtier in the entourage of Henry of Navarre (the future Henry IV) for the royal wedding. Although he was present, his account is informed by interviews with others, not his own eyewitness (as is often claimed), as he would have been with Prince Henry when Coligny was killed and, besides, relates specific details he would have had no way of knowing.

The Texts

The following texts come from The Histories of De Thou as reprinted in Readings in European History by J. H. Robinson, Volume II, pp. 179-183 and from The Fugger Newsletters by George T. Matthews reprinted in The European Reformations Sourcebook, second edition, by Carter Lindberg, p. 189. In De Thou's account, most of the names can be understood in context. The Duke of Guise referred to is Henry I, Duke of Guise (l. 1550-1588), son of Francis, Duke of Guise (l. 1519-1563), who, with his brother, Charles, Cardinal of Lorraine (l. 1524-1574), had advanced the pro-Catholic, anti-Huguenot agenda during the reign of Francis II of France (1559-1560) but had been sidelined by Catherine de' Medici under his successor Charles IX.

The Chevalier d'Angouleme referenced is Henri d'Angouleme (l. 1551-1586), illegitimate son of Henry II of France and so half-brother to Francis II, Charles IX, and Henry III. This would appear to be the same person referenced in the Fugger Newsletter account as "the King's bastard brother," but this makes no sense as Henri d'Angouleme was not killed in the massacre and was a sworn enemy of Protestantism.

François de Montmorency (l. 1530-1579), referenced by De Thou, was the son of Anne de Montmorency (l. 1493-1567), Constable of France, who was related to Admiral Coligny. Anne de Montmorency died fighting for the Protestants in the second of the French Wars of Religion and François, initially loyal to the Catholic monarchy, joined the Protestant cause.

Coligny had been especially effective as a Protestant military leader in the third war (1568-1570) with the financial and moral support of Jeanne d'Albret. His close relationship with Charles IX prior to the third war, despite their religious differences, had earned him the resentment of Catherine de' Medici and others of Henry I, Duke of Guise's Catholic League. His alleged "scheming plots and secrets" referenced in the pro-Catholic account in the Fugger Newsletter, is a reference to the rumors of his influence over Charles IX inciting him to support the Dutch Revolt in the Netherlands by Protestants against Catholic Spain as well as advancing other anti-Catholic agendas.

Death of Admiral Coligny by De Thou

So it was determined to exterminate all the Protestants and the plan was approved by the queen. They discussed for some time whether they should make an exception of the king of Navarre and the prince of Condé. All agreed that the king of Navarre should be spared by reason of the royal dignity and the new alliance. The duke of Guise, who was put in full command of the enterprise, summoned by night several captains of the Catholic Swiss mercenaries from the five little cantons, and some commanders of French companies, and told them that it was the will of the king that, according to God's will, they should take vengeance on the band of rebels while they had the beasts in the toils. Victory was easy and the booty great and to be obtained without danger. The signal to commence the massacre should be given by the bell of the palace, and the marks by which they should recognize each other in the darkness were a bit of white linen tied around the left arm and a white cross on the hat.

Meanwhile Coligny awoke and recognized from the noise that a riot was taking place. Nevertheless, he remained assured of the king's good will, being persuaded thereof either by his credulity or by Teligny, his son-in-law: he believed the populace had been stirred up by the Guises and that quiet would be restored as soon as it was seen that soldiers of the guard, under the command of Cosseins, had been detailed to protect him and guard his property.

But when he perceived that the noise increased and that someone had fired an arquebus in the courtyard of his dwelling, then at length, conjecturing what it might be, but too late, he arose from his bed and having put on his dressing gown he said his prayers, leaning against the wall. Labonne held the key of the house, and when Cosseins commanded him, in the king's name, to open the door he obeyed at once without fear and apprehending nothing. But scarcely had Cosseins entered when Labonne, who stood in his way, was killed with a dagger thrust. The Swiss who were in the courtyard, when they saw this, fled into the house and closed the door, piling against it tables and all the furniture they could find. It was in the first scrimmage that a Swiss was killed with a ball from an arquebus fired by one of Cosseins' people. But finally the conspirators broke through the door and mounted the stairway, Cosseins, Attin, Corberan de Cordillac, Seigneur de Sarlabous, first captains of the regiment of the guards, Achilles Petrucci of Siena, all armed with cuirasses, and Besme the German, who had been brought up as a page in the house of Guise; for the duke of Guise was lodged at court, together with the great nobles and others who accompanied him.

After Coligny had said his prayers with Merlin the minister, he said, without any appearance of alarm, to those who were present (and almost all were surgeons, for few of them were of his retinue): "I see clearly that which they seek, and I am ready steadfastly to suffer that death which I have never feared and which for a long time past I have pictured to myself. I consider myself happy in feeling the approach of death and in being ready to die in God, by whose grace I hope for the life everlasting. I have no further need of human succor. Go then from this place, my friends, as quickly as you may, for fear lest you shall be involved in my misfortune, and that someday your wives shall curse me as the author of your loss. For me it is enough that God is here, to whose goodness I commend my soul, which is so soon to issue from my body." After these words they ascended to an upper room, whence they sought safety in flight here and there over the roofs.

Meanwhile the conspirators, having burst through the door of the chamber, entered, and when Besme, sword in hand, had demanded of Coligny, who stood near the door, "Are you Coligny?" Coligny replied, "Yes, I am he," with fearless countenance. "But you, young man, respect these white hairs. What is it you would do? You cannot shorten by many days this life of mine." As he spoke, Besme gave him a sword thrust through the body, and having withdrawn his sword, another thrust in the mouth, by which his face was disfigured. So Coligny fell, killed with many thrusts. Others have written that Coligny in dying pronounced as though in anger these words: "Would that I might at least die at the hands of a soldier and not of a valet." But Attin, one of the murderers, has reported as I have written, and added that he never saw any one less afraid in so great a peril, nor die more steadfastly.

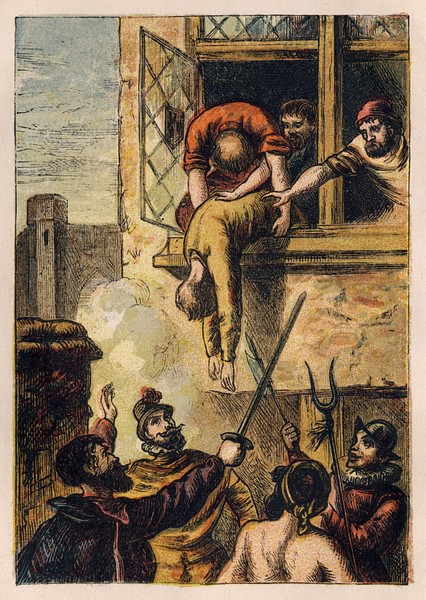

Then the duke of Guise inquired of Besme from the courtyard if the thing were done, and when Besme answered him that it was, the duke replied that the Chevalier d'Angouleme was unable to believe it unless he saw it; and at the same time that he made the inquiry they threw the body through the window into the courtyard, disfigured as it was with blood. When the Chevalier d'Angouleme, who could scarcely believe his eyes, had wiped away with a cloth the blood which overran the face and finally had recognized him, some say that he spurned the body with his foot. However this may be, when he left the house with his followers he said: "Cheer up, my friends! Let us do thoroughly that which we have begun. The king commands it." He frequently repeated these words, and as soon as they had caused the bell of the palace clock to ring, on every side arose the cry, "To arms!" and the people ran to the house of Coligny. After his body had been treated to all sorts of insults, they threw it into a neighboring stable, and finally cut off his head, which they sent to Rome. They also shamefully mutilated him and dragged his body through the streets to the bank of the Seine, a thing which he had formerly almost prophesied, although he did not think of anything like this.

As some children were in the act of throwing the body into the river, it was dragged out and placed upon the gibbet of Montfaucon, where it hung by the feet in chains of iron; and then they built a fire beneath, by which he was burned without being consumed; so that he was, so to speak, tortured with all the elements, since he was killed upon the earth, thrown into the water, placed upon the fire, and finally put to hang in the air. After he had served for several days as a spectacle to gratify the hate of many and arouse the just indignation of many others, who reckoned that this fury of the people would cost the king and France many a sorrowful day, Francois de Montmorency, who was nearly related to the dead man, and still more his friend, and who moreover had escaped the danger in time, had him taken by night from the gibbet by trusty men and carried to Chantilly, where he was buried in the chapel.

St. Bartholomew's Eve: Fugger Newsletter

As [the Admiral of France] was reading a letter in the street, a musket was fired at him from a window. He was but hit in the arm yet stood in danger of his life. Whereupon it is said that the King evinced great zeal to probe into this matter. With this the Admiral did not rest content but is reported to have said he well knew who was behind this, and would take revenge, were he to shed royal blood. So when the King's brother, the Duke of Anjou, and the Guise, and others heard of this, they decided to make the first move and speedily to dispose of the whole matter.

…They broke into the Admiral's house, murdered him in his bed, and then threw him out of the window. The same day they did likewise unto all his kin, upon whom they could lay their hands. It is said that thirty people were thus murdered, among them the most noble of his following, and also Monsieur de La Rochefoucauld, the Marquis de Retz, the King's bastard brother, and others. This has been likened unto Sicilian Vespers, by which the Huguenots of this country had their wings well-trimmed. The Admiral has reaped just payment. We hear that the Prince [Henry of Navarre] and his retinue are being watchful that no such fate befall them. Truly, potentates do not permit themselves to be trifled with, and whosoever is so blind that he cannot see this learns it later to his sorrow. Since the Admiral, as has been reported, has now been put out of the way, it is to be supposed that all his scheming plots and secrets will be brought to the light of day. This may in time cause great uproar, as it is more than probable that many a one at present regarded as harmless was party to this game.

Conclusion

Although Coligny had made it clear he would have revenge for the attempt on his life, and the other Protestant leaders had called for decisive action in finding and prosecuting the would-be assassin, there is no evidence the Protestants were planning an uprising or any kind of military action between 22-24 August 1572. The preemptive strike agreed to by Catherine de' Medici, Charles IX, and the council did nothing to advance the cause of peace, nullified the gesture of the wedding of Henry of Navarre and Margaret of Valois, and led directly to the fourth of the French Wars of Religion which would then rage until 1589, costing thousands of lives.

Even if there had been some suggestion of the possibility of Protestant aggression, Catholic animosity toward the Protestant guests in Paris was already at its height, owing to resentment over the first three wars. Scholar Diarmaid MacCulloch writes:

If French Protestant crowds were militant, so were Catholic crowds, and they were generally more murderous: where Protestants smashed images, Catholics butchered people. There were some rational explanations for their hatred: the loathing that the vast majority of people in Paris showed for the Huguenots over several decades was connected to the campaigns of Protestant forces around the city in the second civil war in 1567, which left permanent memories of the starvation and general misery which they caused. (309)

Catherine de' Medici has often been blamed for the assassination of Admiral Coligny and the St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre, as has Charles IX, but the actual cause was the religious intolerance and hatred of the 'other' that had been steadily gaining support since the Protestant Reformation arrived in France c. 1521. It was this religious intolerance that led to the death of Coligny and, after him, the deaths of thousands more.