The cataclysmic end of the Roman Empire in the West has tended to mask the underlying features of continuity. The map of Europe in the year 500 would have been unrecognizable to anyone living a hundred years earlier. Gone was the solid boundary line dividing Roman civilization from what had been perceived as 'barbarism'. Gone were the familiar institutions of almost half a millennium. And gone was a ruler who could survey the whole of the West as his domain. Instead, the West was fragmented into a patchwork of shifting 'barbarian' kingdoms while the gradually shrinking East continued under an emperor in thrall to a domineering church and overweening eunuch chamberlains.

Though changed in form, monarchy remained the order of the day in the 'barbarian' kingdoms of Europe, balanced by a composite Romano-Germanic aristocracy. The social ethos, aristocratic from time immemorial, survived unchecked, rooted in a general belief in inequality. In religion, the turning point had already occurred prior to the fall of the Western Roman Empire, with the dominance of Christianity by imperial favor, formalized by decree in 380, ending 800 years of religious toleration, or even freedom of worship, and ushering in 1,500 years of religious intolerance and persecution.

Nothing remains exactly the same forever, but it is also true that nothing changes so completely that no trace of its original form is left. What Edward Gibbon characterized as "The indissoluble union and easy obedience that pervaded the government of Augustus and the Antonines" (V. 51) gave way in the 4th century to a fractured society of divided loyalties.

However, even the dissolution of the Western Roman Empire left a hankering after some sort of political unity across at least Western Europe, and more widely, which found expression in the coronation of Charlemagne in 800, followed a century later by the institution of the long-lived but effete and misnamed Holy Roman Empire, then by Napoleon's brief but highly influential ascendancy, and currently by the European Union. In terms of religion, Christianity, whose dominance was established by imperial decree in the 4th century, has remained the principal religion of Europe ever since. And the aristocratic ethos that pervaded the ancient world has effectively survived the concerted efforts to destroy it.

Military Decline

"Roman civilization did not die a natural death," wrote the French historian André Piganiol: "it was assassinated." (Piganiol, 732). Though extreme, this view is not entirely baseless. The long era of Roman military superiority came to a crashing end with the defeat and death of Roman emperor Valens at the hands of the Goths at the Battle of Adrianople in 378. Valens was too impatient to wait for the reinforcements under his brother Emperor Gratian.

But the rot had set in much earlier. After 212, when Emperor Caracalla granted Roman citizenship to all free adult males residing in the empire, military service lost the attraction that it had had for unenfranchised provincials. Up to that time, such men had been prepared to sign up for 25 years in order to be granted the coveted Roman citizenship. So the army now had to look further afield for recruitment, namely to 'barbarians' from outside the Roman Empire, who did not have the same loyalty to Rome, especially when they were allowed to fight under their own indigenous commanders.

The Sack of Rome

Adrianople was serious enough, but worse was to follow. In 410, Rome was sacked by Alaric the Goth, the first time it had been captured since 390 BCE, 800 years earlier. Christians and pagans alike were cast into despair. Even from as far away as Bethlehem, the Christian theologian Jerome lamented: "If Rome can perish, what can be safe?" (Jerome, Ep. 123, 16). In 455, Rome would be sacked again, more thoroughly this time by the Vandals under Genseric.

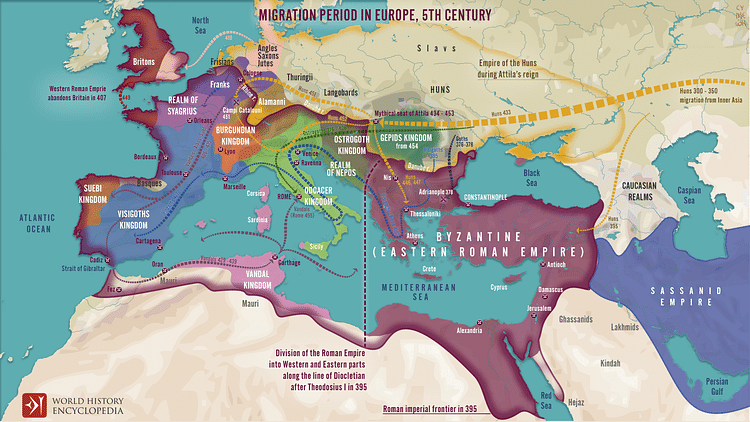

In the meantime, between 407 and 409, the Vandals and their allies crossed the Rhine, swept across Gaul and into Spain. "The whole of Gaul smoked as if on a single funeral pyre," wrote the Christian poet Orientius (Commonitorium, lines 179-184). This was probably something of an exaggeration, but not a total fabrication. It was around this time that Britain was permanently lost to Rome, while Athaulf led his Visigoths from northern Italy into Gaul, living off the land in time-honored fashion, and then made a deal with the Roman emperor Honorius, sealed by marriage to the emperor's sister Galla Placidia. Wallia (r. 415-418), Athaulf's successor but one as king of the Visigoths, was granted land in Aquitaine, which became the base of a Visigothic kingdom covering most of Gaul and Spain. The initial grant of land in Aquitaine was by agreement with the imperial government, but the expansion was achieved by extortion or brute force.

Under Childeric I (r. 458-481) and Clovis I (r. 481 to c. 511), the Franks gained control of most of Gaul, forcing the Visigoths to concentrate, amid internecine conflict, on holding Spain, most of which was finally wrested from them by the Muslims (formerly known as Moors) between 711 and 718.

Italy under 'Barbarian' Rule

Meanwhile, disruptive change was just as relentless back in Italy. The traditional date of 476, marking the formal end of the Roman Empire in the West, is more symbolic than real. But the name of the last western emperor, Romulus Augustus, still holds a certain fascination, combining as it does the name of Rome's eponymous mythical founder with that of Rome's re-founder. In fact, not only the eleven-year-old last emperor but also his predecessors for at least the previous two decades were mere puppets in the hands of 'barbarian' generals. But after 476, Italy as a whole fell under 'barbarian' rule, first under Odoacer (r. 476-493) and then under Theoderic, the Ostrogothic king (r. 493-526). The reconquest of Italy by the Byzantine emperor Justinian (r. 527-565) was short-lived, and between 568 and 774, most of Italy fell under the rule of the Lombards, a Germanic tribe.

Romania, not Gothia

Despite the 'barbarian' successes, Athaulf the Visigoth recognized the strength of Roman tradition:

At first I wanted to erase the Roman name. ... I longed for Romania to become Gothia, and Athaulf to become what Caesar Augustus had been. But long experience has taught me that the ungoverned wildness of the Goths will never submit to laws, and that without law a state is not a state. Therefore I have more prudently chosen the different glory of reviving the Roman name with Gothic vigor, and I hope to be acknowledged by posterity as the initiator of a Roman restoration, since it is impossible for me to alter the character of this empire. (Orosius, Historia Adversus Paganos, 7.43.4-6.)

This declaration would prove to be prophetic. To this day, most of the area previously occupied by the Western Roman Empire now forms part of the European Union, is governed by Roman-based law, and speaks a form of modern Latin, such as Italian, Spanish, Catalan, Portuguese, French, and Romanian. In Britain alone did the language of the conqueror prevail. Yet, the Anglo-Saxon tongue, or Old English, would in due course become so heavily overlaid with French and Latin as to end up at the present day with a majority Latin-based vocabulary.

Power Structure

Another gauge of continuity is the power structure. The power structure of a society is the measure of who has the whip-hand in that society, which correlates to some extent with social mobility, liberty, and equality. The evidence of societies over three millennia reveals that there have only ever been two pure forms of government: monarchy and oligarchy (the latter, if hereditary, morphing into aristocracy).

The long sweep of Roman history constitutes a valuable resource for analysis, combining as it did both forms of government. The Roman Republic, a textbook example of oligarchy lasting almost 500 years (509-44 BCE), was succeeded by the Augustan Principate, three centuries of true monarchy with popular support and an acquiescent aristocracy (27 BCE to 284 CE). Diocletian's short-lived military Dominate (284-305) was succeeded by Constantine's ignoring the lower orders while bringing the aristocracy back into government in the West, where their importance grew until the dissolution of the Western Empire into a patchwork of 'barbarian' kingdoms. The influence of a composite Romano-Germanic aristocracy actually continued well into the Middle Ages, especially in what is now France.

Meanwhile, in the Eastern half of the empire, which split from the West in 395, as what is now known as the Byzantine Empire, the Dominate supposedly continued in force for another thousand years until it finally fell to the Ottomans in 1453. Lacking both the popular support of the Augustan Principate and the counterweight of aristocratic ballast, the apparently all-powerful Byzantine emperors in practice shared their power with overweening eunuch chamberlains and a potent Church.

Social Ethos

While the Roman Empire was a monarchy of one kind or another from its inception under Augustus, its social ethos remained unremittingly aristocratic, based on a fundamental belief in the inequality of human beings. This persists to this day, even while purportedly eclipsed by the egalitarian ideals of the 18th-century Enlightenment. Even the French Revolution drew a distinction between active citizens and passive citizens, granting the right to vote to only about 4.3 million adult male Frenchmen out of a total population of around 29 million.

It is also important to understand that equality is not the same thing as equality of opportunity, which really means equal opportunity to become unequal. For example, the modern goal of eliminating racial, ethnic, sexual, religious, and other forms of discrimination in admissions to higher education is not to produce a uniform society of equal earners all enjoying the same privileges. Instead, the goal is to award higher earnings, greater authority, and greater privileges on the basis of merit, however that is defined. So the age-old belief in the inherent inequality of people still underlies modern western society.

Religious Toleration

Religion is an important area that combines continuity and change. Until 380, when Christianity became the sole official religion of the Roman Empire by imperial decree, Rome had enjoyed over 800 years of religious toleration, and even freedom of religion. Though there had always been a Roman state religion, which was a form of polytheistic paganism, it had never been exclusive. On the contrary, innumerable foreign cults and religions had all flourished largely without let or hindrance. These included Christianity, whose claims to have suffered persecution before winning imperial favor have lately been proved essentially baseless (see Moss).

Why was dominant Christianity intolerant not only of other religions but also of all 'heretical' deviations from the one 'correct' orthodoxy while pagan Rome was a haven of religious freedom? It is because, while Christianity was (and is) a creed religion, Roman paganism was a communal religion. By its very nature, a creed religion stands or falls by the truth of its creed, or set of beliefs, which are held out as the unique key to salvation. Rejection of this creed, or the slightest deviation from it, results in persecution and possibly even death.

Christianity was really the earliest creed religion. In the ancient world, communal religions were the norm. Your membership of a particular nation, state, or society carried with it automatic membership of that society's religion. The Roman "pagan" religion was of this type. There was no separate religious identity. Beliefs did not play a big part in communal religions. It was assumed and accepted that every society had its own religion, and, as a result, conversion was practically unknown. Religious toleration was therefore the norm, and in a cosmopolitan melting pot like Rome, adherence to several different religions or cults was not uncommon.

Christianity's rise to dominance through imperial favor in the 4th century ushered in over 1500 years of religious persecution, religious wars, and burnings at the stake. If Christian countries are more tolerant today than they were even a century ago, it is not because Christianity itself has changed, but because of the secularisation of western society.

Conclusion

In terms of power structure and social ethos, the fragmentation of the Roman Empire in the West does not really represent a turning point. However, in regard to religious toleration, one can draw a straight line from the destruction of pagan temples and the persecution of heretics in the late 4th century to the burnings at the stake and religious wars of over a thousand years later.