Henry of Navarre became the nominal ruler of France after the assassination of Henry III of France (r. 1574-1589), whose marriage to Louise de Lorraine produced no heir. After years of attempts to deny the throne to Navarre, his enemies realized they could not defeat him militarily. The French Wars of Religion had exhausted the country, and it became clear that Henry would need to adopt the religion of the majority of his subjects to assure the freedom of conscience for Protestants with whom he had a religious affinity and who had fought by his side.

Henry of Navarre's Conversion to Catholicism

The arrival of a Protestant king and the weariness of opposing parties imposed the compromise of Henry's conversion to Catholicism. The Archbishop of Bourges announced Henry's intention on 17 May 1593 and two months later, on 25 July 1593, Henry of Navarre solemnly recanted in the Basilica of Saint-Denis at the feet of the archbishop. His abjuration was attacked as feigned by some, yet many citizens simply wanted peace and a nation free from foreign influence. Protestants did not hide their chagrin and requested guarantees from the king, who promised to reestablish an earlier edict of 1577 and its guarantee of religious tolerance. Protestants were permitted to worship throughout the kingdom, even discreetly at the court, and army officials could celebrate the Lord's Supper in the camps. With these conditions, the Protestants provisionally maintained their confidence in their former co-religionist.

Religious and political leaders eventually rallied to Henry, which led to his coronation as King Henry IV of France at the Cathedral of Chartres on 27 February 1594. There he pronounced the traditional oath to drive out from his lands all heretics denounced by the Church. On 22 March, the king entered Paris, and the Te Deum rang out from Notre Dame. Pope Clement VIII (served 1592-1605), vexed by the French Church's absolution of Henry IV without pontifical authorization, distrusted the sincerity of the king. Not until September 1595 did the pope confer his conditional pardon. Protestants, however, ulcerated by the king's abjuration, feared that reconciliation with the pope would lead to renewed persecution and sought to obtain further guarantees of security.

Edict of Nantes & Religious Tolerance

In response to continuing religious violence, on 13 April 1598, the king promulgated an edict of pacification and declared it perpetual and irrevocable, known as the Edict of Nantes. The edict, which imposed religious coexistence, was met with resistance. Henry IV deployed his energy to obtain the registering of the edict in regional parliaments. Rome continued to oppose any change in the Catholic Church's privileged position in France, and Pope Clement VIII declared that freedom of conscience was the worst thing to have ever happened. After years of religious wars, the edict did not immediately extinguish all the grudges and resentment, but it opened a new period in relations between Catholics and Protestants and provided relative security and tolerance for Protestants. The birth of Louis XIII of France (r. 1610-1643) in 1601 assured the perennity of the dynasty.

The Edict of Nantes in 1598 was a watershed in French history and Henry IV's crowning achievement. France established the notion of tolerance and officially proclaimed for the first time that people were free to profess the religion of their choice, although Catholicism would remain the religion of the kingdom. This was an edict of compromise previously unknown in France, granting legal recognition of the Protestant religion and setting limits to Protestant worship. Protestants were still required to pay tithes to Catholic parish priests, observe Catholic feast days, and all religious property that had originally belonged to the Catholic Church was ordered returned. In some places, and in and around Paris, Protestant worship was forbidden within an established radius. Protestants and Catholics had equal rights in providing education for their children. From a political point of view, full amnesty was granted for all acts of war. Civil equality with Catholics was guaranteed, and there was a provision for the right of access to public employment. Those who had fled France were allowed to return.

The edict opened access for Protestants to universities and public offices, and four academies were granted authorization along with the right to convoke religious synods. Protestants were guaranteed the security of their garrisons for eight years in several towns, most notably the port city of La Rochelle. One great novelty was that civil power placed limits on religious domination of society. The Catholic Church recuperated 200 cities and 2,000 rural parishes and resigned itself to tolerance as a necessity of the circumstances of the time. While Protestants were not allowed missionary activity to open new places of worship, Catholics altered the religious map, opening churches in places where Catholicism had virtually disappeared.

In reality, the Edict of Nantes was a treaty with concessions designed to prevent further warfare. The edict, in granting tolerance toward Protestants, had also reinforced the rights of the Catholic Church. Article 3 stipulated that the Catholic, Apostolic, and Roman religion would be reestablished throughout the kingdom to be freely and peacefully exercised without any trouble or obstacle. This authorized the complete institutional restoration of the Catholic Church in every corner of the kingdom, even in places where the majority of habitants had converted to the Reformed faith, in cities like La Rochelle, Montauban, and Montpellier, and in vast regions like the Cévennes, Dauphiné, and Vivarais. In all these places, Protestants now needed to prepare for the return of priests who had been absent for two generations. Catholic processions resumed in places where there had been none for decades. Tensions were often high in cities with two places of worship, two cemeteries, two categories of the king's subjects, and even two church bells.

The edict's importance lay in a changed perspective of the individual. As a political subject, the individual was expected to obey the king, regardless of confession. As a believer, the subject was free to choose his religion, which was now considered a private matter. Protestants retained territorial possession of places of safety in more than 100 cities in France, including La Rochelle, Saumur, Montpellier, and Montauban. During this period of tolerance, these cities became states within the state. They held political assemblies, developed territorial organization, maintained military fortresses, and practiced diplomacy and relations with foreign powers, notably England. La Rochelle became the principal bastion of the Reformed religion and was supported by England, which sought to curb the development and expansion of the French navy.

Unraveling the Edict of Nantes

The edict was enforced during the reign of Henry IV, at times with great difficulty, until his assassination in 1610. He survived multiple plots and attempts to assassinate him before falling at the hand of a Catholic zealot, François Ravaillac, on 14 May 1610. His death alarmed the Protestants who feared the loss of their acquired rights. Marie de' Medici (1575-1642) became queen following her husband's death. She confirmed the Edict of Nantes in a declaration on 22 May 1610, but Protestants had little confidence in her. The Estates-General gathered in 1614 and 1615, at which the Protestants perceived that the nobility and the clergy were prepared to consider the edicts of pacification as provisory. They were also alarmed by the proposed marriage of Louis XIII (1601-1643) to Anne of Austria. Three provinces, Languedoc, Guyenne, and Poitou took part in an uprising led by malcontent lords. Marie's negotiations with them resulted in the Treaty of Loudun, which granted six more years of protection for Protestant cities of safety.

The protections enjoyed under Henry IV began to unravel and were gradually removed after his death. Long before its revocation in 1685 under Louis XIV of France (r. 1643-1715), the edict was undermined through inconsistent application and interminable bad faith complaints lodged against Protestants. The Edict of Nantes had not established equality between the religions. Protestants received political advantages and were simply tolerated as long as they practiced their religion within the strictures imposed on them. The first ten years of the 17th century following the Edict of Nantes marked a Catholic renewal. The king flattered himself that France might return to religious unity. To this end, funds were established (Caisse de conversion) to pay pastors who converted to Catholicism. The times changed from religious wars to religious controversies and were marked by conversions between the two religions; monks embraced the Reformed religion, and pastors turned toward Catholicism. Henry IV had several Protestant collaborators, and to his credit, during the 15 years of his reign, he lifted his wartorn nation out of decades of civil war. However, he refused to reunite the Estates-General and create a parliamentary monarchy that might have protected the nation from coming abuses of power. He oriented the nation toward absolutism which offered him a stunning if brief splendor, which would lead to bloody reactions.

The presence of Protestant strongholds became intolerable for Henry IV's successor, his son Louis XIII. Under him, the domination of the Catholic clergy grew rapidly. The king took a Jesuit for his confessor, and his new minister, Charles-Albert de Luynes, pledged to exterminate the heretics. At the general assembly of Catholic clergy in 1617, Louis XIII, instead of respecting the will of his father, ordered the restitution of possessions to the Catholic Church. He marched on to the province of Béarn, took the stronghold of Navarriens, and reestablished Catholicism. The abuses committed against a majority Calvinist population foreshadowed the future dragonnades, a form of persecution under Louis XIV where Protestants were forced to lodge the king's cavalrymen (dragons) to induce Protestants to convert to Catholicism.

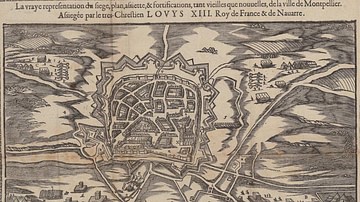

In response to the king's actions, the Huguenot general assembly at La Rochelle in December 1620 divided France into eight quasi-military regions with leaders, which triggered Catholic opposition. Most of Midi took up arms, but the rest of the country did not move against the king. He went on to besiege Montauban, which resisted heroically for two and a half months and forced the king to lift the siege on 2 November 1621. The king besieged Montpellier in August 1622, but the city defended itself so valiantly that the king agreed to negotiate. The siege was lifted, and the Peace of Montpellier, signed on 18 October 1622, confirmed the Edict of Nantes and granted amnesty, but forbade political assemblies without royal authorization. Only two stronghold cities remained: La Rochelle and Montauban.

The years 1622 to 1625 were marked by incessant squabbles and acts of violence between the parties. In 1625, Rohan in Languedoc and his brother Soubise in the western regions engaged in military campaigns without decisive results. The Peace of Paris was signed on 5 February 1626 and maintained the status quo until Cardinal Richelieu passed into action.

Cardinal Richelieu & the Siege of La Rochelle

Marie de' Medici had succeeded in introducing Armand du Plessis de Richelieu (1585-1642), now wearing a cardinal's hat, into the court of Louis XIII in 1624. Richelieu was prime minister during the reign of Louis XIII (r. 1610-1643). He was a man of great ambition and capacities, a strict defender of the Catholic cause in France, intending to break all opposition to royal absolutism. Louis XIII and Richelieu sought to force the submission of Protestants to royal authority and reinforce the unity of the kingdom. The city of La Rochelle stood as a formidable barrier to their designs and had become the principal stronghold of the Huguenot party.

La Rochelle had largely adhered to the Protestant Reformation, was responsible for the dissemination of Protestantism in western regions of France, and had become a refuge for Protestants fleeing other places. Richelieu's attempts to negotiate with La Rochelle failed in 1625, and he was forced to sign the Peace of La Rochelle in February 1626. In 1627 the conflict was reignited and La Rochelle was besieged for a year, encircled, and cut off from all outside provision. Richelieu ordered the construction of an enormous dike to prevent all help from the sea. The last months of the siege were marked by a devastating famine, obliging women, children, and the elderly to leave the city and wander destitute through the marshes, where few survived. Those besieged survived by eating horses, dogs, and cats, with hundreds dying daily of famine. La Rochelle had a population of 25,000 before the siege, of which 18,000 were Protestant, and little more than 5,000 when the blockade ended.

The expedition mounted by the Duke of Buckingham failed due to his assassination and La Rochelle capitulated on 28 October 1628. The next day Richelieu entered the city and celebrated a solemn Mass in the Church of Sainte-Marguerite. Louis XIII entered La Rochelle on 1 November to receive its surrender, followed by a great procession on 3 November. The king abolished all the former benefits the city enjoyed, ordered most of the ramparts leveled, turned the churches over to the Catholic Church, and created a bishopric. Louis XIII had the Notre-Dame des Victoires built in Paris in honor of his triumph. Ten years later he would consecrate France to the Holy Virgin and institute the Feast of the Assumption. After years of sacrifice, La Rochelle's destiny was now tied to the French monarchy and the Catholic Church.

Conclusion

In June 1629, with the Edict of Grace (Peace of Alès) under Louis XIII, negotiated by Richelieu with Protestant leaders, Protestants experienced the loss of many earlier gains. The edict maintained the concessions of the Edict of Nantes but dismantled the Protestant party. Reformed pastors had the right to preach, celebrate the Lord's Supper, baptize, and officiate at marriages only in villages and cities authorized by the Edict of Nantes. Protestants, who had contributed to the restoration of the unity of the kingdom were now considered factious in the face of a centralized unity sought by the great ministers, Richelieu and later Mazarin. The dragonnades replaced the Wars of Religion as Protestants lost their princes and protectors. Louis XIII ordered the demolition of Protestant places of safety and the reestablishment of Catholic worship. Although Protestants theoretically retained religious rights for another 50 years, they lost political influence and were progressively excluded from public functions. These rights were slowly undermined under Louis XIII's successor, his son Louis XIV and eventually abrogated in 1685.